Fifty years ago today Alaska was slammed with a 9.2 earthquake. It occurred at 5:36 p.m. and its epicenter was about 90 kilometers west of Valdez and 120 kilometers east of Anchorage, according to the Alaska Earthquake Information Center.

Deaths numbered more than 100 and included 16 in Oregon and California, most of them from tsunamis. The quake damaged over an area of about 130,000 square kilometers, and was felt in an area of about 1,300,000 square kilometers. That’s all of Alaska, parts of Canada and south to Washington.

The Homer area and southern Kenai Peninsula escaped the worst tragedy: no one died in the quake.

Coincidentally, the quake happened just as the new city of Homer came into being. On Monday, the city celebrates its 50th birthday. On March 31, 1964, the city of Homer became official when an Anchorage Superior Court judge certified incorporation. Voters earlier on March 10, 1964, had approved incorporation with 258 for and 141 against. Court approval came just a day before an April 1 deadline for the city to receive title to tidelands under a bill introduced in the Alaska Legislature by Rep. Clem Tillion.

The quake hit during mild weather with a light snow on an ebbing tide. High tide had been 19.4 feet, and the low tide was at 7:30 p.m. According to a U.S. Geological Survey report by Roger Waller, “Effects of the Earthquake of March 27, 1964, in the Homer Area, Alaska,” quake-generated waves hit Kachemak Bay, but spared the Homer Spit and other areas because of the low tide.

Eyewitnesses reported waves rolling in from Seldovia across Kachemak Bay, two coming in like an inverted V a mile long on each side. Most waves were parallel to the shore and about 10-feet high. An observer on Perl Island in the Chugach Islands reported a 28-foot wave hit the island. Halibut Cove reported a tide of 24 feet. Waller wrote that most of the waves were not actual tsunamis from the uplift of the seafloor in Prince William Sound, but from movement of the seafloor during the quake or submarine landslides, such as slumping of the delta in front of the Grewingk Glacier.

General damage in Homer included chimneys knocked down, plate-glass windows, dishes and glassware broken, and cracks in some foundations, such as the Inlet Inn Hotel, now the Driftwood Inn. One car was thrown up against the wall of Vern Mutch Drug, now the Duncan House. Power went out for 17 minutes and long-distance telephone service was lost. The ice collapsed on Beluga Lake and seiche waves rippled across it — earthquake-generated waves from shaking.

Similar effects were reported up the coast to Anchor Point and Ninilchik. Many people lost wells or had wells silt up. Some had well pumps burn out when pumps tried to move silty water, Waller reported.

Most people reported being thrown to their feet and unable to move during the worst of the quake.

Waller wrote that Tex Sharp, owner of the Waterfront Bar, couldn’t cross the 10 feet from his apartment to the bar for four minutes.

“When the shaking stopped, he entered the bar in his bare feet, and found his stock of bottled goods and glassware almost totally destroyed,” Waller wrote.

One woman, Mrs. Gus Weber, said she saw two moose run into a clearing where they “jumped, bucked up and down like horses, reared up on their hind legs and ran back and forth as the earth moved in all directions,” Waller wrote.

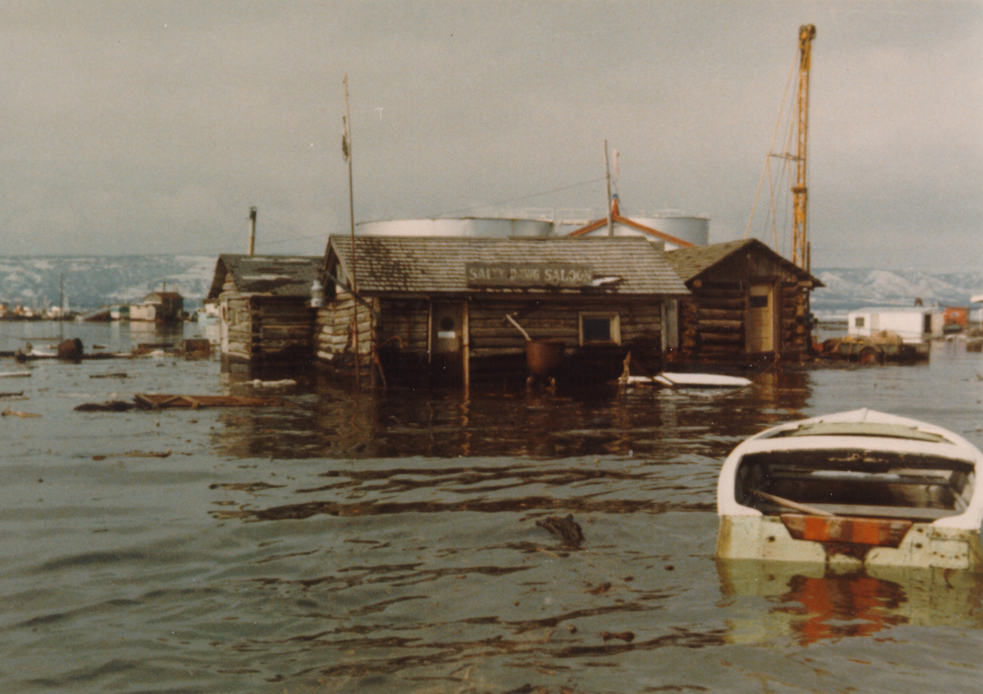

The major effect of the quake on Homer was subsidence of the Homer Spit, which fell 5.9 feet, much of that from ground compacting. The mainland subsided about 2.5 feet. The Spit collapse destroyed the small boat harbor, sucking away the seaward side of the harbor, and flooded a fuel tank farm and buildings such as the Salty Dawg Saloon and the Porpoise Room. Many old timers recall with some poignancy the loss of Green Timbers, a wooded park in what’s now Louie’s Lagoon.

“It was where we went for Sunday picnics and romantically inclined young people found a place to park,” Wilma Williams wrote in a description of a photo showing the flooding of Green Timbers.

When the spring tides came in, only the outer storm berms remained above water. Storms pushed rocks and gravel onto the Spit, creating a new berm and rebuilding the beach. Nature didn’t rebuild the Spit, though.

Property losses in Homer totaled $1 million. With the new city in place, it could accept federal disaster relief money, about $2.5 million for the reconstruction of Homer. Much of that went to building a new small-boat harbor, and that lead to the resurrection of the Homer Spit. Out of dredging spoils and using fill, from the Homer Marine Terminal to Land’s End, the Spit rose from the sea.

To the people of the southern Kenai Peninsula who lived through the 1964 earthquake, mention it and memories awaken that are as real as if the event had just occurred. The sound and shaking. The destruction and devastation. The horror and the humor.

Mike De Vaney

Homer

Having just turned 16, Mike De Vaney and a friend were working on De Vaney’s 1959 Pontiac Catalina on the late afternoon of March 27, 1964. They had the car up on the rack at Airport Texaco, a former Homer business that was located at the corner where Ocean Drive turns right to become Spit Road.

“When the earthquake hit, we didn’t have time to let it down, so we stood there a minute and watched that silly car go back and forth and then the cement building started to get cracks in the walls and we left it and ran out into the middle of the road,” said De Vaney.

The intense movement caused the “ground to go up and down like giant swells,” said De Vaney.

As he and others tried to keep their balance, the swells grew to such height that a vehicle approaching on Ocean Drive would completely disappear from sight each time it dipped into the trough of those swells.

“It was wild,” said De Vaney. “(The driver) kept coming down the road. It struck us as so bizarre that he wouldn’t stop.”

He also recalled seeing the trees whipping back and forth and laughed at another observation locked in his memory.

“We didn’t see any seagulls or any birds at all,” he said. “I don’t remember why I would ever pay attention to that after all these years. That it stuck with me is weird.”

Inside the service station, a cash register had been shaken onto a class counter, breaking the glass. A window also was broken. When the shaking subsided, De Vaney lowered his car and drove to his family’s home on Klondike Avenue.

Concerned about how the quake might have impacted their boat and others, De Vaney and his father immediately headed out the Spit. Upon discovering boats had been shaken loose of their moorings, the father and son did their best to make them secure.

Before long, the extent of the quake became known, making it clear Homer “wasn’t real bad,” said De Vaney. That didn’t minimize the impact of the aftershocks, however.

“They were almost as spooky as the actual quake,” said De Vaney. “During the night, when we’d have them I couldn’t help but wonder if it was going to be another big one.”

Wilma Williams

Homer

Enjoying a late-afternoon cup of tea with friends at Martha’s Café, a business that was located near the current site of Bay Realty and across Pioneer Avenue from where Wilma Williams and her husband, Charlie, were living at the time, Williams said there had been a jolt and disruption to electrical power earlier in the afternoon.

“A gal had run into a telephone pole and knocked all the lights out around town,” said Williams.

So, it was laughable when the earthquake began and someone came into the café and said, “It wasn’t me.” The frequency of earthquakes in the area also made it funny when someone shouted, “Yahoo. Ride ‘em, cowboy.”

However, the strength of the quake soon made it clear this one was no laughing matter.

Eager to get to the couple’s children in the family home, Williams’ husband maneuvered the swelling ground and dodged swaying power poles and snapping electrical lines to cross the street. Williams made it to the house within seconds of her husband, who already had one child clutched to him and had a second one by the hand and was headed for the door, sidestepping furniture being tossed around by the quake.

Worried about two more children that were playing with neighborhood friends, Williams said she “forgot about having a car and I was running down the road to see where those kids were. I could see them coming and every time the ground would roll, they’d sit down and try to hold onto the ground.’”

Like De Vaney, Williams said news made it clear how serious the quake had been.

“We turned the radio on and it would be saying, ‘Mrs. Jones is looking for her little girl, Nellie. If anybody knows her whereabouts, the mother is at such-and-such a place.’ It kept on with those sorts of messages until I finally took the radio and put it on the top shelf. I didn’t want to hear anymore of that,” said Williams.”

The self-sufficiency of southern peninsula residents proved a key in the days following the quake.

“We didn’t depend on anything but ourselves,” said Williams. “We had a heater and we had coal. … As far as food, we had moose meat on the shelf, homemade jellies, canned fish. So, we could ride out the bad times. It probably would have taken a couple of months before we would have started running out of things.”

Jim Rearden

Homer

In his book “Old Alaska, Events of the 1990s,” Homer author Jim Rearden dedicates an entire chapter to the events of March 27, 1964.

“The earthquake struck while three of us were conferring in the Homer office of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. As the building violently leaped, file cabinet drawers slid open, over balancing the cabinets, which crashed to the floor dumping loads of papers all directions. Loose objects fell. The noise was overwhelming. ‘Let’s get out of here,’ I yelled, and leaped to my feet,” was Rearden’s description of what happened when the shaking began.

Outside the building, he and the others “stared in amazement” as cars leapt and the tops of spruce trees whipped about.

Making his way home, Rearden found his family frightened, a window that had cracked and damage done to his water system. The loss of electricity was only temporary, back within 20 minutes thanks to a diesel standby plant.

Anchorage radio stations, the ones that were still operating with emergency power, offered little news other than “a large earthquake had struck Anchorage.” Returning to the ADFG office, Rearden tried to make contact outside the area via a two-way radio.

“I was curious when I headed for the Fish and Game office that evening and snapped on the radio. I had little idea there had been a major disaster affecting much of Alaska,” he said.

Although the radio had not been a reliable form of communication in the past, on that night it enabled Rearden to make contact with Juneau officials who were unable to contact Anchorage. It also allowed Rearden to begin gathering information about the extent of the damage. Seldovia residents had moved to high ground, hoping to avoid flooding. Water levels were surging up and then out in Peterson Bay. The USCGC Sedge reported it was hard aground near Cordova and that “all the water around her had drained away.”

In the days that followed, Rearden was part of a communication network that helped identify the missing and dead, none from Homer, deliver personal messages and broadcast lists of supplies needed.

Darlene Crawford

Seldovia

With a day of work as Seldovia’s city clerk-treasurer done, Darlene Crawford, her husband and their four young children had just gathered around the family’s small dining table for dinner when the house began moving.

“I grew up in Seward so I was used to earthquakes, but this seemed like it lasted a really long time,” said Crawford.

This quake was different in other ways, too.

“It was more like being on a boat, not up and down and jerking,” she said.

After the quake stopped, someone directed the family to get to higher ground to avoid a possible tsunami. Instead, the Crawfords went to the home of friends at the same elevation as the school and spent the night listening for news on a shortwave radio.

“My folks lived in Seward and we heard Seward was hit bad. I didn’t hear from them until the next day, so there was a lot of praying while we were waiting,” said Crawford.

Also the next day Seldovia residents assessed the damage. Harbor floats were in pieces and boats were loose of their moorings, but there was no damage to buildings, said Crawford.

It was later in the year when big tides flooded waterfront houses and businesses built on pilings and the town’s main thoroughfare, a picturesque boardwalk, that the real changes took shape.

“That was a very traumatic time,” said Crawford. “We didn’t have damage from the earthquake, really, except for the sinking, but the damage to the town was created by Urban Renewal.”

In a close vote — Crawford thinks it was as close as 30-34 — Seldovia residents approved an Urban Renewal project.

“They bought out four canneries and the hotel that had water going in and out and the houses along the slough, tore them down … put a lot of fill there, compacted it, put in big armor rock along the edge and made new land where previously houses had been on stilts,” said Crawford. “Some people said, ‘aren’t they going to build anything?’ They had the idea that if they (Urban Renewal) tore down, they’d rebuild, but that wasn’t the idea.”

Eventually, the town spread across the newly created area, but only one of the four canneries returned to the once booming fishing community.

“Seldovia has never been the same since,” said Crawford. “It’s still beautiful, but in a different way.”

Janet Clucas

Seldovia and Ninilchik

Janet Clucas, her husband Bob and their sons were taking a few days away from their Ninilchik cabin to visit friends in Seldovia in March 1964.

“We were just sitting down to eat when we felt it,” said Clucas of the earthquake that began rocking their hosts’ home near the Seldovia Slough. “And then about the time we felt it, the earthquake really started. We couldn’t hardly stand up.”

Making it to the doorway, the two families held on while everything around them shook.

“The trees looked like rubber bands, flipping back and forth,” said Clucas. “About two minutes into it, we heard this horrendous roar and then it seemed like it went on for another three minutes.”

Fear of a tidal wave raced through the community.

“People were running up and down the street yelling to get to the school,” said Clucas, who joined the crowd of women and children heading for the higher ground the school offered. “The men were running to the harbor to the boats.”

Radio communication with the boats assured that many of the boats had made it out of the harbor, avoiding a wave of water that rolled into Seldovia Bay. Those that didn’t “got banged up pretty badly,” said Clucas.

About a week and a half later, the Clucas family returned to Ninilchik. The cabin was undamaged. In the root cellar beneath the cabin, all of Clucas’ canning efforts still sat on the shelves, unmoved, “but people whose shelves were facing the other direction lost everything,” she said.

To this day, it is the sound of the quake Clucas remembers most.

“Every time I feel a tremor, I wait for the roar,” she said. “That big horrible roar.”

Richard Hawkins

Ninilchik

With his mother preparing dinner and his older brother working on homework, Richard Hawkins, who was 13 at the time, was practicing the piano when the earthquake struck.

“The first thing I noticed was that the lamp on top of the piano went out. Hmm, OK, that was nothing new. Then all of a sudden, I felt the earthquake,” he said.

While his immediate thought was, “Oh goody, I don’t get to practice the piano anymore,” his first action was to join his mother in the doorway of an arctic entry.

From where they stood, they witnessed the chimney collapse on the stove and the piano move across the floor about five feet. Cupboard doors flew open. The family’s dog ran back and forth.

When the shaking didn’t let up, Hawkins’ brother came out of his bedroom to join them in the doorway.

“As soon as he got there, a big wall of books fell down,” said Hawkins.

Hanging on for balance, the mother and sons watched trees “whipping back and forth.” Finally, after about five minutes, the shaking stopped.

“We took a quick inspection of the house and other than some of the chinking (between the logs) coming out, the house was in good shape,” said Hawkins.

That evening, the three walked over to the neighbors and spent several hours listening to an emergency broadcast station.

“As we were walking over, I remember seeing all these little bitty cracks on the road,” said Hawkins. “They weren’t open, but you could see that it had cracked.”

Some earthquake damage was slower to make itself known.

“The water table disappeared and we lost our well,’ said Hawkins. “We had to have another one drilled that summer.”

Michael Armstrong can be reached at michael.armstrong@homernews.com. McKibben Jackinsky can be reached at mckibben.jackinsky@homernews.com.