While gathering coal on Mariner’s beach with her husband and friends one day in 1976, Judy Winn of Homer found a curious piece of — something.

“I sort of wandered and was beachcombing and found it in the rocks,” said Winn of spotting the object that was about 20 inches long, seven inches in diameter. “I took it home thinking it was a piece of petrified wood. Then, I was looking at it, the shape, how it was curved, and I kind of got the idea it might be ivory.”

Having read somewhere that a simple test to tell rock from ivory was to burn it, Winn put her discovery to the test, hoping for results that would identify what she had found.

“I cut a little piece off and it burned,” she said.

Over the years, Winn showed her find to others, including local historian and author Janet Klein. Klein even includes it in her book “Kachemak Bay Communities — Their Histories, Their Mysteries,” and the possibility the piece came from a woolly mammoth.

In the past couple of years, radiocarbon dating of 10 pieces found by others between Mariner Beach and Clam Gulch has indicated woolly mammoths inhabited the area between the Penultimate and the Naptowne glaciations, a period about 25,000-60,000 years ago. When a piece fell off Winn’s object, she decided to have it radiocarbon dated and see where it fit on that timeline.

The answer: It is a woolly mammoth tusk, but its age puts it outside the peninsula’s ice-free slice of time.

“The radiocarbon date is 20,400, so it falls right at the peak of the Naptowne Glaciation,” said geologist Dick Reger of Soldotna, referring to a time when ice blanketed the area. “So, we’re not sure where it came from.”

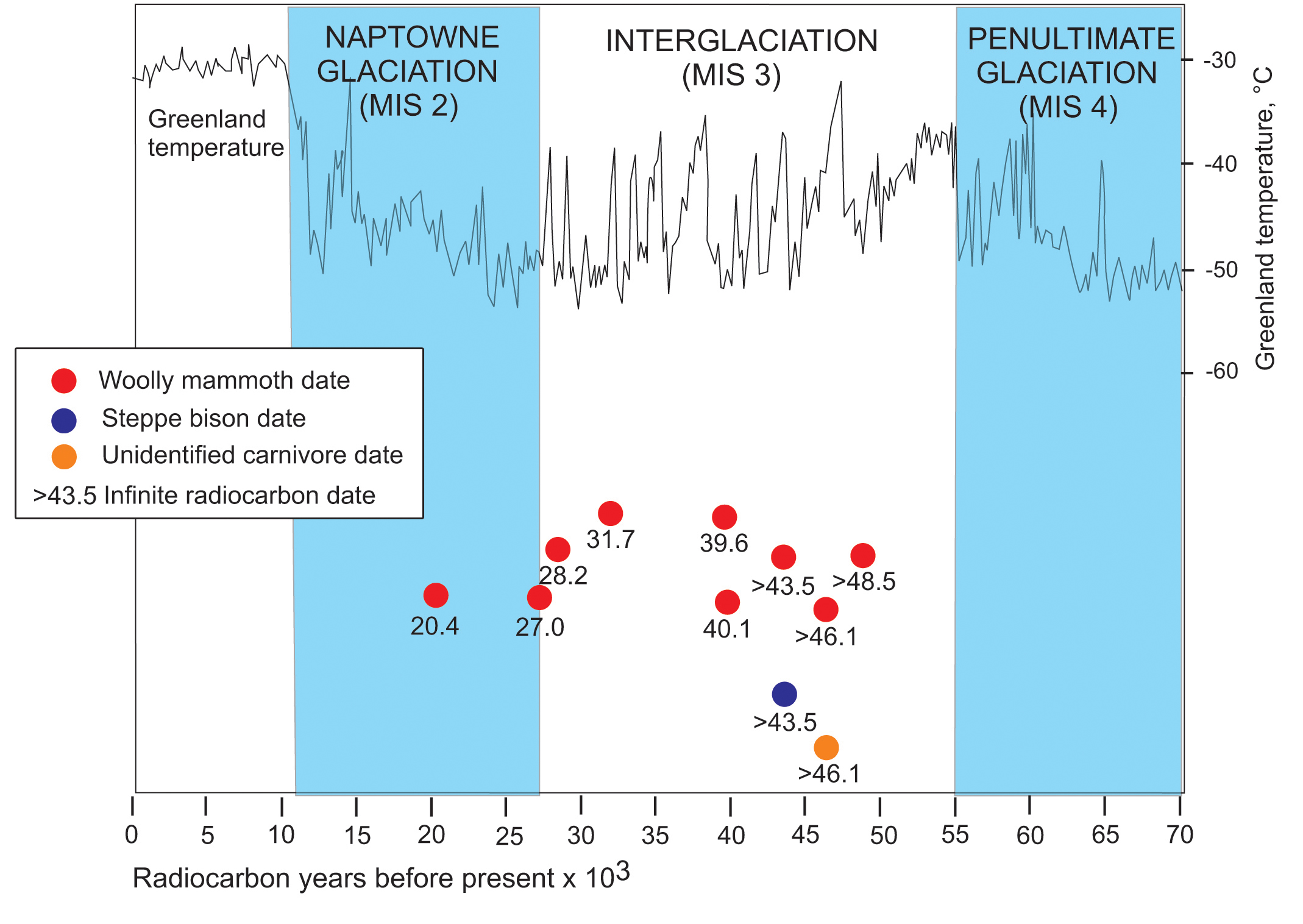

To illustrate, Reger referred to a schematic he developed. From left to right, the baseline represents radiocarbon years before the present time. A jagged line running horizontally across the page represents the Greenland temperature between today and 70,000 years ago as interpreted by cores from the Greenland ice sheet.

“Superimposed on that, shown in blue, are two glaciations, the Naptowne, or latest glaciation, and the Penultimate Glaciation on the right,” said Reger.

Red dots indicate the radiocarbon dating of eight woolly mammoth fragments that fall within the inter-glacial period. They range from 27,000-48,000. A blue dot indicates the radiocarbon results of a steppe bison horn at 43,500; a gold dot represents an unidentified carnivore at 46,100.

Winn’s woolly mammoth tusk “is almost 7,000 years younger than the previous date. … It’s too young, younger than other fauna we’ve found,” said Reger. “All the other dates are clustered nicely with what we know of glacier chronology, but this one is different. It’s not what we expected.”

So, what does that mean? For an answer, Reger examined the condition of the tusk.

“This chunk of tusk looks pretty fresh,” he said. “That would be consistent with a younger age, but may also be consistent with it being brought in from somewhere else.”

Also to be considered is Winn’s finding it on top of the ground surface on the Spit after the 1964 9.2-magnitude earthquake that caused the Spit to sink.

“That makes me think it was brought in and left for some reason or maybe washed in,” said Reger. “Anything sitting on the surface during the earthquake would be subsequently buried by stuff coming in, and yet this was found right on the surface, so that’s a little bit suspicious.”

The tusk’s geographic origin remains a mystery.

“Right now I’m thinking it probably was dumped there after 1964, but whether it was brought in from up the inlet or someone brought it in from Bristol Bay or the Interior, we don’t know,” said Reger.

A past experience provides Klein with a possible explanation. Years ago, a neighbor wanted to show her a portion of a woolly mammoth tusk found in Interior Alaska. Then the neighbor remembered her grandchildren had taken it out in the field to play with and wasn’t sure they’d brought it back inside.

“It’s probably still out there somewhere,” said Klein, considering something similar may explain the presence of the piece Winn found.

“So, a radiocarbon date from when the peninsula was totally under ice, what does that tell you? That it probably came from somewhere else,” said Klein.

What does all that mean to Winn and her memory of the day more than 35 years ago when she was gathering coal and beachcombing on Mariner Beach?

“The carbon dating proves it probably didn’t come from this area. It might have come from Bristol Bay or Fairbanks. Who knows,” she said. “I don’t know where or when it came from except that I found it on the beach.”

McKibben Jackinsky can be reached at mckibben.jackinsky@homernews.com.