From time to time, we reshare past Refuge Notebook articles. We selected this article as part of our efforts to commemorate the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge’s 80th year.

It is especially relevant because it speaks to important historical events and the different management techniques used over the years to steward these lands, waters and wildlife for the benefit of current and future generations. We hope you enjoy this article originally written by Brandon Miner for the March 8, 2002, Refuge Notebook.

Moose habitat management has a long and colorful history on the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge.

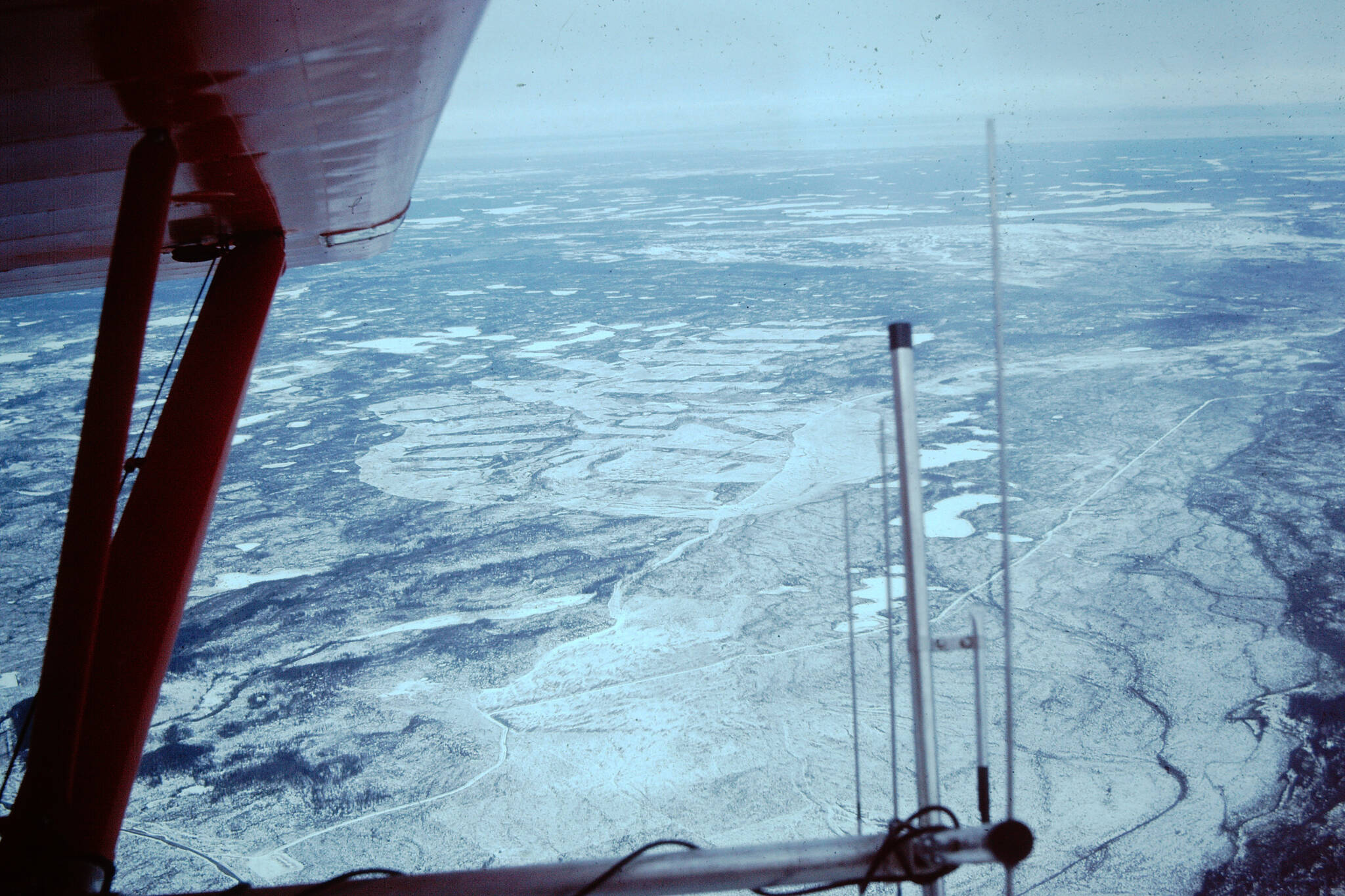

It all started with a huge 310,000-acre wildfire in 1947 that came to be known as the ‘47 burn. It got an important boost in 1969 from an 86,000-acre fire north of Kenai, called the ‘69 burn.

In the 1950s, managers of the moose range (as the refuge was called prior to 1980) observed that black spruce seedlings were growing prolifically in the ‘47 burn. Black spruce has little food value for moose, and so the moose range launched a war on black spruce.

From the 1950s through the 1980s, thousands of acres of young forest were mechanically manipulated by methods ranging from hand-pulling of seedlings to behemoth 40-ton tree crushers.

The tree crushers were deployed in the 1970s in the ‘47 and ‘69 burns to stimulate stump sprouting and root suckering of hardwood browse, such as aspen, birch and willow, and to break off spruce trees. The tree crushers were about the size of a road grader and had three large steel wheels that broke pole-sized trees into 3-foot lengths, mostly without disturbing the underlying soil.

Tree crushing was effective, but it cost a lot of money, both for operator time and for expensive repairs of the machines. The crushers were sold in 1988, having accomplished about 20,000 acres of treatment.

Between 1970 and 1980, the goal of tree crushing on the moose range was to convert young black spruce stands to early succession hardwood stands. This was optimistically called “type conversion.”

Generally, hardwood species are faster growing and more sun-loving than spruce and are able to aggressively colonize an area after a disturbance (such as fire or crushing). Over a period of decades, however, spruce usually catches up and shades out most of the hardwoods.

By the mid-1980s, it became apparent that crushing alone was failing to accomplish type conversion from spruce to hardwoods. Crushing reduced black spruce density, but did not expose mineral soil for good hardwood germination.

Something else was needed. So, in 1986, the refuge undertook prescribed burning, with the hope that fire could achieve the hardwood browse production that mechanical treatment failed to deliver.

In 1998-99, I conducted a forest regeneration study on the refuge for my master’s degree thesis project. My goal was to evaluate the results of the black spruce campaigns of the last half-century. Had all this effort accomplished anything? What methods worked best?

I studied 11 sites that had been burned, crushed, or crushed-and-burned from 11 to 52 years in the past. I found that hardwood browse regeneration was best at sites (in the Skilak Loop and Lily Lake areas) that had been crushed and burned with prescribed fire in the 1980s.

Before crushing, these areas were primarily young black spruce in the ‘47 burn; in 1999, these areas contained an average of 7,700 stems per acre of browse species, which is a lot of moose food.

Browse density was also relatively high in the 1969 burn at 5,700 stems per acre, although much of the birch and aspen has now grown beyond the reach of moose. The areas that we surveyed within the older (untreated) 1947 burn averaged only 800 browse stems per acre. Browse densities at sites that were simply crushed with no subsequent burning contained an average of only 2,400 stems per acre.

Overall, I concluded that the crushing-and- burning combination was much better than either crushing or burning alone.

Mechanical pre-treatment of a forest creates a continuous fuel bed (a layer of down, dead woody fuel), which allows a surface fire to burn at high intensity and consume the ground fuels (moss and duff). This exposes more mineral soil much more effectively than a fire carried in the canopy of standing live trees. We like to see good mineral soil exposure from a fire because seeds germinate best on mineral soil.

On the other hand, light to moderate severity burns in areas where hardwoods are scarce can stimulate grass invasion and prevent reforestation for decades. But if aspen and willow are abundant before burning, a light to moderate severity burn can stimulate good stump sprouting and root suckering.

One very practical advantage to mechanically pre-treating a stand is that we can burn under damper conditions than are required for standing live forest. It is easier to get a good fire going in dead wood on the ground than in upright green timber. This means that we need fewer firefighters on hand, and there is less chance of the fire escaping control.

Sometimes people ask, “Why worry about burning the forest? Why not just leave things the way they are?” Fires are a natural part of the ecosystem on the Kenai Peninsula. They have occurred regularly ever since deglaciation 13,000 years ago, as we have seen in our lake sediment charcoal studies.

With the increasing human population on the peninsula, however, we have to suppress many wildfires to protect life and property. Prescribed burning gives us a chance to achieve the same results of natural fires, but on a smaller scale and under more controlled conditions.

In addition to providing moose browse, fire in the forest recycles important mineral nutrients, increases soil temperatures, and prepares a seedbed for new seedlings. On a scale of decades to centuries, fire creates a vegetation mosaic or patchwork of uneven-aged stands that is beneficial to many types of birds and animals.

Snowshoe hares, for example, benefit from abundant browse, as do all the animals that prey on hares, such as lynx, wolves and birds of prey. Indeed, fire provides the base of the food chain in our forests.

Although prescribed burning has recently received somewhat of a “black eye” because of several well-publicized mishaps on public lands, it still is one of our best habitat management tools. Since the 1980s we have successfully used prescribed burning on the refuge to enhance wildlife habitat and provide good fire breaks, and we have gotten our best results when we were able to mechanically pre-treat the fuels before burning.

Brandon Miner began working on the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge in 1998; he completed his master’s degree from Alaska Pacific University in 2000. His master’s research summarized 50 years of vegetation manipulations on the refuge. Find more Refuge Notebook articles (1999–present) at https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Kenai/community/refuge_notebook.html and stay connected https://www.facebook.com/kenainationalwildliferefuge