On the night of Jan. 23, Alaskans across the Gulf Coast were awakened by one of the most significant earthquakes to hit Alaska since the Good Friday Earthquake of 1964.

Among them was Joel Curtis, the National Weather Service’s warning specialist in Juneau.

As he got into his car and drove to the office, he was stricken with a wave of dread.

“I was really, really afraid when I got to work,” he recalled in an interview earlier this month. “I thought Alaskans were going to die.”

Curtis, like almost everyone on that night, believed the Magnitude 7.9 earthquake would be like the Magnitude 9.2 earthquake of 54 years ago. That earlier disaster spawned a tsunami that killed more than 120 people across Alaska, the West Coast and Hawaii. It remains Alaska’s deadliest natural event and irrevocably changed the state.

“The subduction zone major earthquake … is the disaster that keeps our folks awake at night. That’s probably the most serious, deadly thing that we face in Alaska,” said Mike Sutton, director of the state division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management.

Six months ago, only a fluke of geology and plate tectonics prevented that disaster. Instead of moving the seafloor vertically, triggering a tsunami, January’s earthquake moved it horizontally, in what seismologists call a “strike-slip” movement.

Instead of a 30-foot wave on Kodiak Island, there was one 9 inches tall.

What could have been a disaster was instead the state’s most comprehensive disaster drill since 1964. Thousands evacuated their homes, and the state’s warning system was put to the test. In the hours following the all-clear, initial indications were that all went well. Alaskans received their warning and evacuated.

“Thanks to you and your very capable team for how the earthquake notification was handled this a.m.,” Gov. Bill Walker wrote to Adjutant General Laurie Hummel that morning.

But an extensive public records request performed by the Empire reveals more to that story. Emails and reports show the state’s tsunami warning system experienced several critical failures on the night of Jan. 23 and left the Emergency Alert System to be activated by a single intern at the National Weather Service in Anchorage.

Some of the flaws identified in January have been fixed. Others, as indicated by a false alarm in May, remain unresolved.

Five fingers

For most Alaskans, warning comes by a strident tone broadcast over the radio and TV. In May, that message came in the middle of the morning commute. In January, it came in the middle of the night.

That tone, and the robotic voice that follows it, comes from the Emergency Alert System, a nationwide program created by the federal government in the 1990s to survive any disaster up to and including a nuclear war. (The system replaced an older one designed specifically to deal with that kind of war.)

In January, and again in May, that system mostly worked as designed. Radio stations across coastal Alaska heard the EAS tones, picked them up, and rebroadcast the warning as intended. Alaskans took note and evacuated (or prepared to evacuate, in the case of the false alarm). That wasn’t the problem.

The activation of that system was the problem. In January, the quickest activation methods failed. In May, the system wasn’t supposed to be activated at all.

To understand how activation works, imagine the Alaska Tsunami Warning Center in Palmer, a building filled with experts, equipment and communications. Put that building in the center of your palm and stretch out your fingers. Each finger represents one way the alert spreads.

One finger is the fiber-optic line to FEMA’s computer server in Kansas. From there, an alert goes to cellphone providers, the internet and more.

Another finger goes to the FEMA alternate operations center, which links to emergency warning centers along the West Coast of the U.S. and Canada. Those centers can use a hard-wired telephone network connected to warning stations along the coast.

A third finger goes to Alaska’s emergency operations center, which can spread the warning by phone to local communities’ separate, disconnected warning systems. The people at that center, on Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson in Anchorage, are also charged with coordinating a response to the disaster.

A fourth finger goes to National Weather Service offices across the state. They in turn activate NOAA weather radios, and if an EAS message goes out over those radios, it also triggers the statewide system.

A fifth finger goes to EMNet, the satellite-based system controlled by a contractor hired by the state.

Each of these fingers can touch the other and activate the EAS, spreading a warning across the state. The state emergency operations center, for example, can turn to EMNet and spread the warning. EMNet sends messages into the Integrated Public Alert and Warning System (IPAWS). An EAS message broadcast on NOAA weather radio can be picked up by commercial radio and TV stations and spread. FEMA’s Kansas server can trigger EAS as well as alerts on cellphones.

Those cross-connections matter because a disaster might break one or more of those fingers.

In January, it didn’t even take a disaster to break them. Three of the five fingers failed as a result of technical glitches, deliberate action, and human error.

‘How the hell did that happen’

When the earthquake struck at 12:32 a.m., people and systems worked as intended at the tsunami warning center in Palmer. The center’s goal is to issue a tsunami alert or all-clear message within five minutes. According to an after-action report by the National Weather Service, the center did it in three. (An independent analysis by the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute corroborated that timing.)

The center promptly posted an alert on its website, which was promptly slammed by enough internet traffic that it was largely unusable for the night. There were so many phone calls coming into the center that its phone exchange crashed, temporarily knocking out service.

The warning center sent an alert into FEMA’s system, known as IPAWS, which responded in seconds, funneling a 90-character message into the national Wireless Emergency Alert system.

At 12:36 a.m., cellphones across Alaska started buzzing with terse and identical messages: “Tsunami danger on the coast. Go to high ground or move inland. Listen to local news. – NWS”

For those who didn’t feel the shaking of the earthquake, this was the first chance at warning, but not every cellphone received an alert.

The wireless alert system depends on cellphone providers, cellphone towers and cellphone owners. If a tower isn’t updated with the proper equipment or software, it won’t spread the message. If a cellphone company doesn’t support the system, the message won’t arrive. If the owner of a cellphone has it in “do not disturb” mode (and doesn’t make an exception for these alerts), the message will not arrive.

Because of difficulties with targeting alerts, the WEA system also spread warnings to people who didn’t need them, such as Anchorage residents.

In Alaska, most AT&T and Verizon customers got the message. Most GCI customers did not. GCI does not automatically support these emergency messages. It requires customers to download a separate app. Heather Handyside, a spokeswoman for GCI, said recently that company expects to roll out automatic support by the end of the summer.

The IPAWS alert wasn’t limited to cellphones; the handful of services with automated internet-based warnings also carried the word. The Anchorage Police Department, for example, spread the alert at 12:38 a.m. through Nixle, the Twitter alternative for government services.

Critically, however, the Weather Service deliberately disabled the feature of IPAWS that would have activated the state’s EAS network. The Weather Service feared the possibility of duplicate warnings, so it disabled the feature — and didn’t tell anyone.

Worse, because they had received warnings on their cellphones, state emergency managers believed the EAS network had been activated.

“When we were coming into the office, we assumed it went through IPAWS to all of the broadcasters,” Bryan Fisher, the state’s emergency program manager, said by phone.

Internal emails obtained by the Empire via a records request show emergency managers learned about the issue on the morning after the earthquake.

“I am going to contact NOAA about this. WOW!” wrote Mark Roberts, manager of the state’s emergency operations center.

“OMG. How in the hell did that happen. Holy CRAP!” wrote Dennis Bookey, co-chair of the Alaska State Emergency Communications Committee.

With IPAWS disabled, the fastest means of activating the EAS network went with it.

Problems in Florida

Without IPAWS to quickly spread an alert, the EAS network should have been triggered by the satellite-based EMNet. That didn’t happen.

“I received what was apparently a WEA alert at 00:36 on my phone but the first NWS/EAS alert arrived at 01:02,” wrote Rich Parker, director of engineering for CoastAlaska, the umbrella organization for public radio stations along the Gulf coast.

“As for EMNet/IPAWS/etc — nothing but ‘crickets’ — is that normal?”

Since 2016, the state has had a $134,000 per year contract with Communications Laboratories Inc. of Melbourne, Florida, to provide satellite-capable warning connections.

ComLabs, as it is known, is supposed to scan the warning channels operated by the National Weather Service. When an alert arrives, its duty is to feed the warning into satellite dishes placed at radio stations across the state. Those stations will then activate the EAS.

On the night of the earthquake, this system did not work, and the documents obtained by the Empire do not contain any evidence that anyone knew it was not working.

Three days afterward, ComLabs CEO Roland Lussier emailed Roberts to explain what happened. Sometime on the 22nd, ComLabs’ main server crashed. The technician on duty contacted another technician to fix the problem, but that person didn’t check to see whether the crash had interrupted ComLabs’ duty to watch for alerts.

“He did not properly perform his responsibilities,” Lussier wrote.

The main server was online, but not processing, which meant that when the backup server received and properly processed and received the alert, it was only on standby and didn’t send the message onward.

“I consider this failure to be extremely serious in nature,” Lussier wrote. “I am fully aware of the potential for loss of life involved in this failure.”

Old-fashioned methods

With two of the state’s principal warning channels disabled, that left the oldest and slowest methods: radio and telephone.

Under the state’s EAS plan, the National Weather Service is supposed to trigger the alert network with its collection of weather radios. Those radios are controlled by the state’s three forecast offices: Anchorage, Fairbanks and Juneau.

On the night of the earthquake, the Fairbanks office had been disabled by a power failure at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. The office has no backup generator, and the Alaska Earthquake Information Center (which is housed in the same building) was in the same situation, and so was the Alaska Rural Communications System, which uses a satellite uplink. If that uplink had been online, it could have spread the EAS message as well.

In Anchorage, according to the Weather Service’s account of events, sending the alert fell into the hands of an intern with less than one year on the job.

When the intern tried to use the computer system designed specifically to send tsunami warnings, it failed. The intern then turned to the backup method, copying and pasting an alert message to each of Anchorage’s weather radio transmitters manually.

There were problems in the process, but the first alert went out over the radio at 12:51 a.m., nearly a half-hour after the earthquake struck the Gulf.

The problems persisted in Anchorage afterward; only the first alert went out — subsequent alerts were not carried by weather radio there.

In Juneau, the weather radio functioned as designed.

From the weather radio stations, the alert was picked up by commercial radio stations, which heard the warning tones, automatically recorded the alert message, and rebroadcast it outward. Each message can take up to two minutes to broadcast, which means there is a delay each time a station rebroadcasts the alert.

While slow compared to the newer systems, the radio-based EAS network worked. The sole failure was in Homer, where public radio station KBBI didn’t rebroadcast the alert. Warning messages were carried by public officials, cellphones and the internet, however.

Warnings covered the coast by 1:15 a.m., 30 minutes before the first wave was supposed to reach the Kodiak archipelago. Workers at the state emergency operations center had been calling local officials since the tsunami center’s first warning, spreading the word. Most were already aware.

“They were all, we’re shutting the phone down because we’re getting ready to go up the hill with the rest of the community,” said Sutton, head of the state division of emergency management.

At 1:29 a.m., the state’s emergency operations center activated its auto-dialing system to send out phone calls and emails to isolated locations that might have missed the warning.

By that point, people in Kodiak, Sitka and elsewhere along the coast were already headed to high ground and awaiting a wave.

After-action reports

When the wave failed to arrive, Alaskans waiting in shelters and on high ground were able to go home and fall back asleep.

For emergency managers, it was a short rest before the debriefing began. While some problems were revealed within hours, others took days and weeks. The National Weather Service finalized its after-action report in March; Alaska’s emergency officials also finished their retrospective that month.

Some of the problems revealed in January have been addressed or are being addressed. ComLabs changed its procedures within hours of EMNet’s failure to include more internal checks. Weather Service offices fixed procedures with the system that carries alert messages. TV and radio broadcasters have been fixing hiccups in their equipment. The failed phone exchange at the tsunami warning center has been upgraded, and the Weather Service is working on ways to beef up its website. Cellphone providers are rolling out new equipment to fix gaps in the wireless alert system.

Other problems have not been fixed.

At the University of Alaska Fairbanks, the building that houses the Weather Service offices and the Alaska Earthquake Information Center still lacks an emergency generator.

“AEC is investigating generated standby power but current budget constraints make this unlikely in the near future,” according to the state’s internal report on the Jan. 23 earthquake.

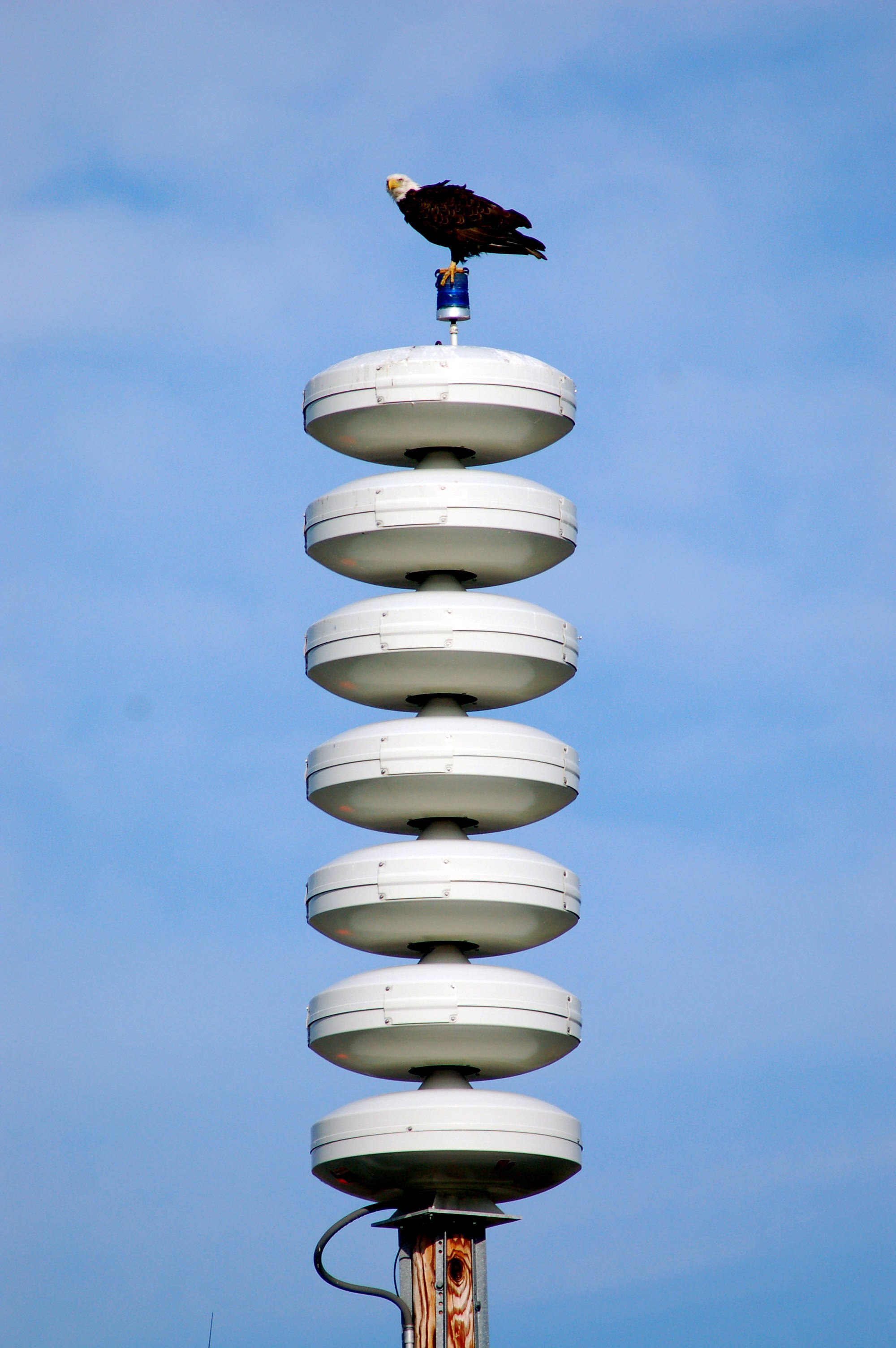

Communities along the coast told the state that many of their residents did not hear warning sirens, and some sirens remain broken.

The IPAWS system remains disabled, and there are no immediate plans to change that fact, despite pleas from state officials to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, parent agency of the Weather Service.

“NWS is not using the nation’s most up to date alerting system,” Roberts wrote in an April email to NOAA.

False alarm reveals additional problems

As emergency officials concluded their analysis of the January alarm, they were confronted by a new problem. On May 11, EMNet systems triggered a false tsunami warning under a test run by the National Weather Service.

“Look folks, I mean WTF?” wrote one radio broadcaster to state emergency officials after the false alarm spread through the EAS network.

In phone calls and emails with state officials, Lussier of ComLabs said the issue was caused when EMNet failed to correctly interpret the code of a test message. Lussier said the Weather Service has repeatedly changed the way it formats its code, and it is difficult to keep up.

In an emailed statement, NOAA spokeswoman Susan Buchanan said the Weather Service “routinely communicates any planned product changes” to developers.

Lussier, contacted by phone and email, declined to make further comments, saying the emails can speak for themselves.

Afterward, Adjutant General Laurie Hummel, director of the Alaska Department of Military and Veterans Affairs (home agency to the state’s emergency management program) asked whether the state’s contract with EMLabs contains a performance clause.

It does not, Sutton told the Empire by phone.

EMNet is not the only outside company to have experienced problems with the changing codes. In February, ComLabs competitor Accuweather transmitted a false tsunami warning for the East Coast under similar circumstances. In April, Texas experienced a false tsunami alarm from a smartphone application that likewise passed along a Weather Service test.

“We’re not unique to that,” Sutton said by phone of the false alarm.

The state has not made any changes to its contract with ComLabs, which expires in 2021. Fisher, director of the emergency operations center, said he would like to see more coordination on codes via the National Tsunami Hazard Mitigation Program, a panel of state and federal agencies, to avoid similar problems.

“It’s our job to protect everyone’s lives out there,” he said.

“There’s a potentially high chance of killing people if we don’t get it right.”

• Contact reporter James Brooks at jbrooks@juneauempire.com or 523-2258.