“Public and permanent.”

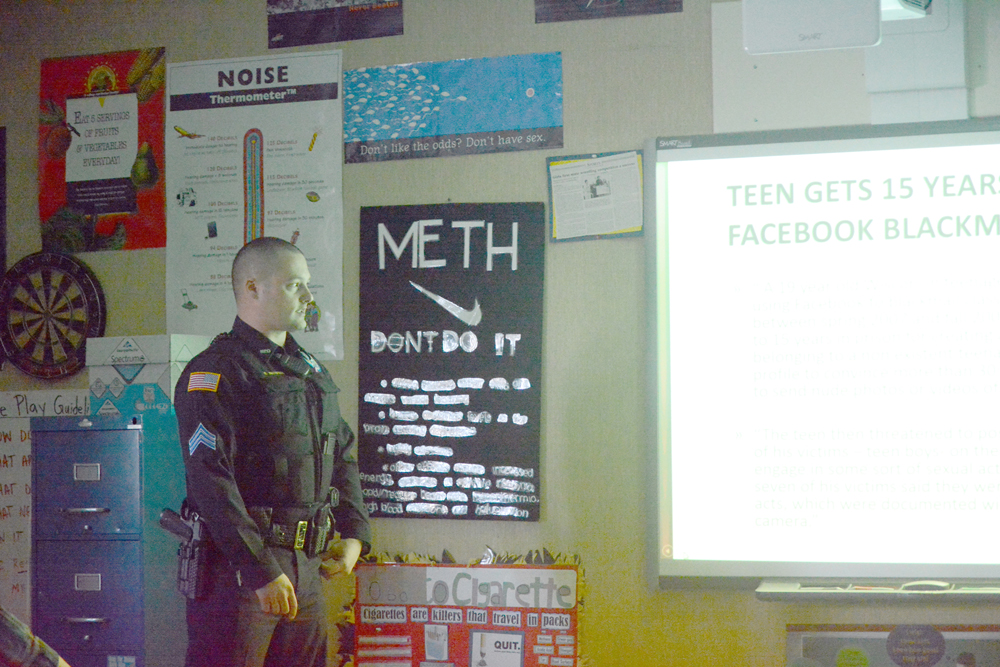

That’s the catch phrase Homer Police Sgt. Ryan Browning kept repeating in a talk on digital con- sciousness he did last month at Homer High School health and physical education classes.

Browning, a Homer High School graduate and former Alaska State Trooper, has been with Homer Police for the last four years. Using some of the ideas on digital con- sciousness put forth by Richard Guerry of the Institute for Respon- sible Online and Cell-Phone Com- munication, Browning emphasized cause over effect as a way to avoid the bad consequences of irrespon- sible computer and cell-phone use.

“I’m here to give you guys digi- tal consciousness, digital awareness — to get you guys to think before you get in hot water,” Browning said to teacher Chris Perk’s 9th- grade class in one presentation in late April.

The widespread use and popu- larity among teenagers of smart phones, tablet computers and other digital devices has led to both good and bad uses.

Social media programs or apps like Facebook, SnapChat and Ins- tagram let people communicate in- stantly and widely through words, photos and videos.

“This thing is a miracle in my hand,” Browning said, holding up a smart phone. “I’m connected to the world.”

With digital devices, teenagers can share harmless information — what they’re wearing to the prom or photos of cute puppies — as well as some bad stuff. Youth sometimes share photos of intimate body parts that under some laws might be con- sidered child pornography.

Girlfriends and boyfriends sometimes coerce partners into tak- ing nude photos and sharing them.

That image might stay on the friend’s smart phone, but what if it doesn’t?

“The message we should be trying to get out there is the minute you hit the send button, the whole world’s going to see it,” said Homer Police Chief Mark Robl.

A lot of teenagers “sext,” said Lilli Johnson, a peer educator with the R.E.C. Room’s Promoting Health Among Teens, or PHAT, program. She and PHAT educators Kaylynn Bunnell and Jonas Noomah spoke on Monday with the Homer News at the R.E.C. Room. The PHAT team also listened to Browning’s presentation before he gave it in the schools and offered a teen perspective.

“It’s common,” Johnson said of sexting. “A lot of people don’t think there’s anything wrong with it.”

Bunnell defined sexting as taking and sending lewd photos of genitals, butts and female breasts. The PHAT educators said that one of the more common apps used in sexting is SnapChat.

With SnapChat, people send a photo with a text to another digital device that shows up for 10 seconds after being answered and then disappears. The recipient can take a screen capture, but if that’s done, the program sends a notice to the sender. The recipient also can take a photo of the screen using another smart phone without the sender knowing it.

Homer Police have been aware of sexting among underage teenagers. Police also have some tools to investigate, Robl said. Under a federal grant through the Internet Crimes Against Children program, Homer Police officers Larry Baxter and Jim Knott have been trained in forensic computer analysis related to sexting and other issues.

Not many parents or teenagers have reported sexting, Robl said.

“I think the victims are embarrassed about it and don’t want us involved,” he said. “And there’s not much we can do for them.”

That is, unless the situation involves minors and an adult, including teenagers age 18 and older. Homer Police have investigated several cases, and since last December, four men have been charged in cases related to inappropriate or illegal online contact with minors (see story, this page).

Noomah said some teens have the attitude that the message “don’t sext” is like telling kids to wear seatbelts. It’s not bad until you get into a crash. Johnson said it’s like the old message of sex being something scary. Sexting is taught as a no-tolerance thing.

The same kind of conversation comes up with drugs and alcohol, Bunnell said. Anna Meredith, the R.E.C. Room coordinator, pointed out another message peer educators make, that the adolescent brain isn’t the best tool for making decisions that can affect people for the rest of their lives.

“We should be teaching safety when we do these things,” Bunnell said.

Browning mentioned other digital dangers like cyberbullying and sextortion. Like bullying, cyberbullying is where people bully people online through messages or social media. Sextortion is where someone allows another person to take a lewd photo or video, and then those images are used to get sexual favors.

Sexting and sextortion can be against the law. Browning pointed out two aspects of Alaska law regarding sexual consent and transmitting sexual images that might seem contradictory. Two teenagers age 16 or 17 can legally consent to sex, but if a one takes a lewd photo and sends it to the other, that could be distribution of child pornography.

“Personally, that feels weird to me,” Johnson said of the discrepancy in laws.

The PHAT educators talked about how when they talk about safe dating, consent is emphasized.Consent doesn’t always happen in sexting. According to an Indiana University study, one in five respondents said they had engaged in sexting when they did not want to.

“The issue of coercion is super important,” Bunnell said. “Sexting has to be consensual.”

“It always comes back to consent,” Noomah said. “If you give a photo when they make a decision to distribute it without consent, that’s where the wrong thing is happening.”

In his presentation, Browning showed a video made by a teenager, Amanda Todd of Vancouver, B.C. Todd mistakenly sent an image of her breasts to a boy.

“It’s out there forever,” Browning said.

That image came back to haunt her, and Todd was teased and bullied. Even after switching schools and moving, other teens harassed her, even assaulted her. Todd wound up killing herself, Browning said after showing the video.

Browning’s message was clear: Don’t address the effect. Address the cause. Schoolchildren do fire drills to be prepared for the unlikely event of a school fire. Digital consciousness is the same way. Fire is a tool you treat with caution. Use digital devices with the same kind of care. Guard online privacy. Protect your online reputation. Assume nothing online is private and assume everyone is watching, Browning said.

Robl encouraged parents to be involved in their children’s digital lives.

“There are some parents who are really aggressive in monitoring and protecting their kids,” Robl said. “Those are the ones we hear about on the periphery. They don’t need our help. They’ve got it.”

For other parents, Robl said Homer Police are happy to help if they suspect sexting or other digital issues.

“The best strategy is to confront their child to start with and see what they can learn,” he said. “The best way to handle it is prevent it. Stop it. Don’t do it.”

PHAT is working on a video about sexting that should be out at the end of the month on the R.E.C. Room’s YouTube channel, R.E.C. Room of Homer, Alaska, Johnson said. The peer educators also suggested several websites for more information (see box, this page).

Resources on digital awareness:

“Public and Permanent,” by Richard Guerry

Available through the Institute for Responsible Online and Cell-Phone Communication

www.iroc2.org

Suggested by PHAT peer educators:

sexetc.org

Sexual education by teens for teens

Loveisrespect.org

Information about dating abuse, including articles on sexting

Thatsnotcool.com

Information about sexting and other issues