A vessel design firm hired by a Prince William Sound environmental watchdog group is skeptical of the capability of tugs being built to escort oil tankers out of Valdez.

Marine engineer Robert Allan told members of the Prince William Sound Regional Citizens’ Advisory Council board of directors on Jan. 19 that his company found “fairly significant deficiencies” in the designs of two classes of tugs that Edison Chouest Offshore plans to use in the sound starting next year.

Allan is executive chairman of the Vancouver-based naval architecture and marine engineering firm Robert Allan Ltd., which was founded by his grandfather and carries the family name.

Last June, Louisiana-based Edison Chouest Offshore announced it had won the 10-year contract from Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. for Prince William Sound ship escort and response vessel system, or SERVS.

Alyeska operates the Valdez marine oil terminal as part of its duties overseeing the Trans-Alaska pipeline system, or TAPS.

At the time, Edison Chouest Alaska leaders said the company would use its in-house shipbuilding capacity to build five new escort tugs and four smaller support tugs to fulfill the SERVS obligations.

The escort tugs generally will usher tankers through the larger sound while the support tugs primarily will be used in the confined waters of the Valdez narrows and for tanker docking.

The small fleet of new tugs is currently under construction at four shipyards in Louisiana and Mississippi, three of which are owned by Edison Chouest, according to Alyeska SERVS Operations Manager Mike Day. They were designed by Damen Shipyards Group, a Dutch company.

Early in his presentation to the council board, Allan acknowledged his company is a regular competitor of Damen and that his opinions could be construed as “a sort of petty jealously or whatever, but I would like to assure the room that that is absolutely not the case,” he said. “We’ve looked at this as professional engineers.”

Edison Chouest is scheduled to take over SERVS operations in July 2018 from an Alaska wing of Florida-based Crowley Maritime Corp., which has provided tanker docking services in Valdez since the startup of the pipeline in 1977.

It added the Prince William Sound escort and spill response duties to its work in 1990, a year after the Exxon Valdez oil spill.

Since then, Crowley has executed the SERVS contract virtually without issue.

The Prince William Sound Regional Citizens’ Advisory Council was established at the behest of a group of Cordova fisherman shortly after the Exxon Valdez spill as a means to improve communication between the public and Alyeska. The 1990 federal Oil Pollution Act mandated the formation of citizens’ councils in Prince William Sound and Cook Inlet.

The council is primarily funded by Alyeska Pipeline Service Co., which is owned by the three major North Slope producers.

Based on the information available, Allan said he could foresee multiple problems stemming from the basic hull designs of the tugs as well as an apparent lack of amenities and equipment to handle cold weather and onboard snow and ice.

“We don’t see enough detail dealing with the whole issue of working in the Alaskan climate and the meta-ocean conditions these boats are going to encounter,” Allan said.

Overall, he said both designs also lack necessary cold-weather features such as heating for exposed deck areas, piping and rope storage lockers along with de-icing for window wipers.

His company was able to review drawings and specification sheets for both classes of tugs along with other vessel description, performance and simulation reports, but not all of the detailed design information available, according to Allan.

Right away he said he was struck by the low expectations for Bollard pull — the total force a tug can exert — for both the escort and support tug designs given the power of the engines and overall size of the tugs.

The Bollard pull projection for both vessel classes is about 15 percent less than what he would anticipate, Allan said, noting that the tugs should still meet duty requirements but could strain winches, tow fittings and other equipment if the power is underestimated.

“It’s not a trivial issue and I just don’t understand why the predicted Bollard pull for this much horsepower is as low as it is,” Allan told the board.

The pull for the 140-foot escort tugs with 12,300 horsepower is approximately 150 tons; for the 102-foot support tugs with about 6,000 horsepower Damen estimates the Bollard pull to be 72 tons.

An apparent decision to rely on computer simulations to determine the seakeeping ability of the escort tugs — how they will fare in various wave conditions — also concerns Allan.

He said top-end performance calculations, based on the information his company was provided, had “only been performed for flat calm conditions, so we don’t know how this performance will deter in weather, which is quite honestly a difficult thing to prove analytically. It can be done through model testing, however.”

Large vessel designers often build downsized scale models of new hull designs that are tested in pools as a way of replicating sea conditions the vessel is likely to face.

A report generated from computer simulations determined the escort tugs capable of handling 4.5-meter seas at speeds of 1 knot, but did not test the design performance in rough water at speeds up to 10 knots, which the tugs will often be operating at, an omission Allan said he finds “worrying.”

Additionally, “four-and-a-half meters is not sufficiently high to address seakeeping, particularly for the sentinel tug applications (where Prince William Sound meets the Gulf of Alaska) so I’m very, very skeptical about the seakeeping predictions in particular,” Allan said.

Edison Chouest Alaska leaders did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

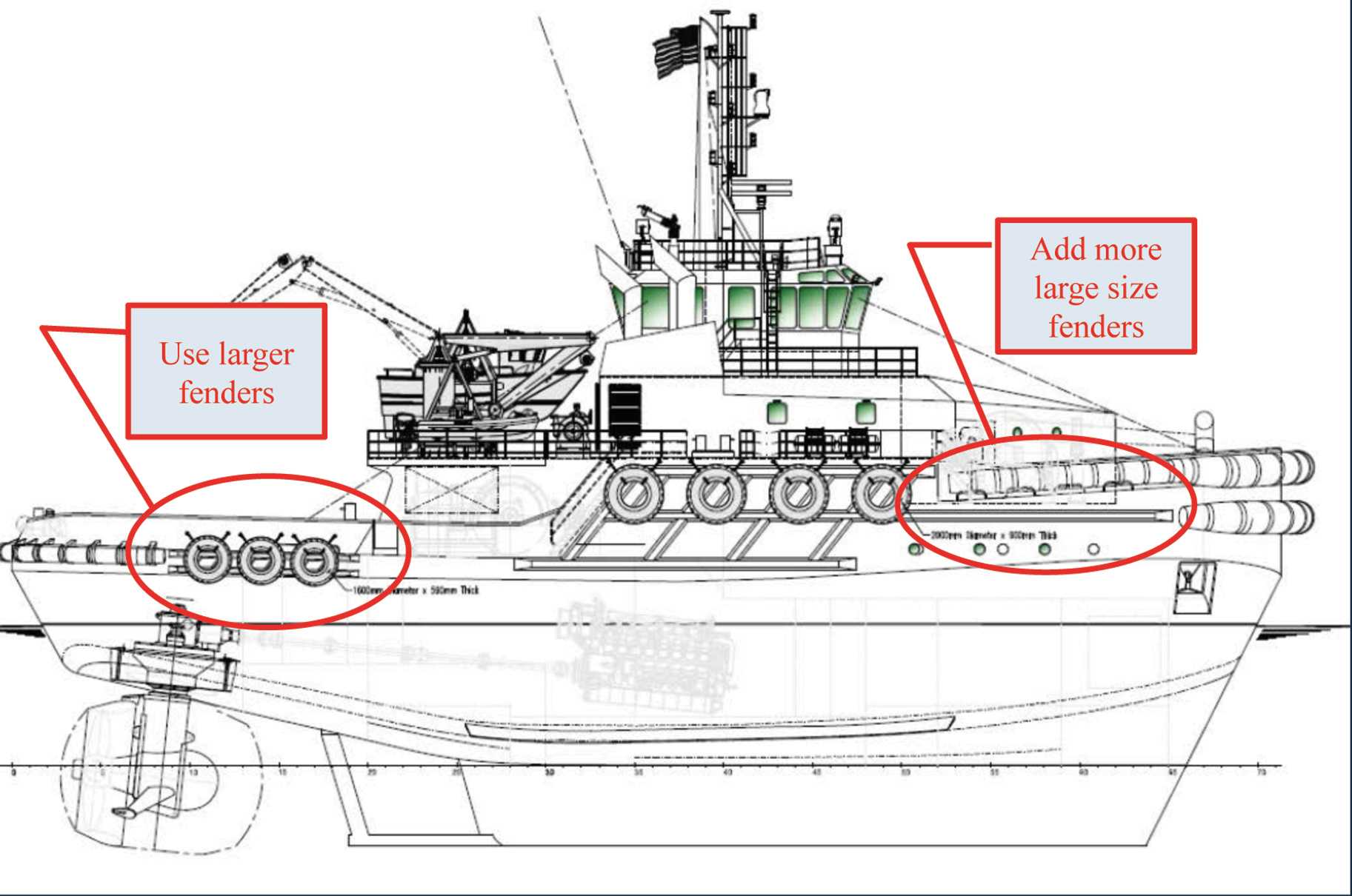

Other potential issues with the escort tug design include a very large skeg that could impact maneuverability at low speeds and blunt bow that might cause the tugs to lose speed in large waves, he commented.

Allan suggested adding bow thrusters to add agility to the escort tugs at low speeds and in tight quarters.

He said further that a three-foot step down to the front deck of the escort tugs, meant to lower the towing point and improve indirect towing performance, “creates a potential swimming pool in the foredeck.”

“If this ship is in heavy seas and sticks its nose into one wave — now you’ve got a meter deep pool of water in the foredeck which has got to find its way out through a series of freeing ports that may well be blocked with snow or ice and then the tug has to rise up to meet the next wave and we’ve added lord know how many tons of water to the foredeck,” Allan described. “I see this as a pretty significant fundamental design problem and it’s not easy to overcome without significantly reducing the indirect towing capabilities of the boat.”