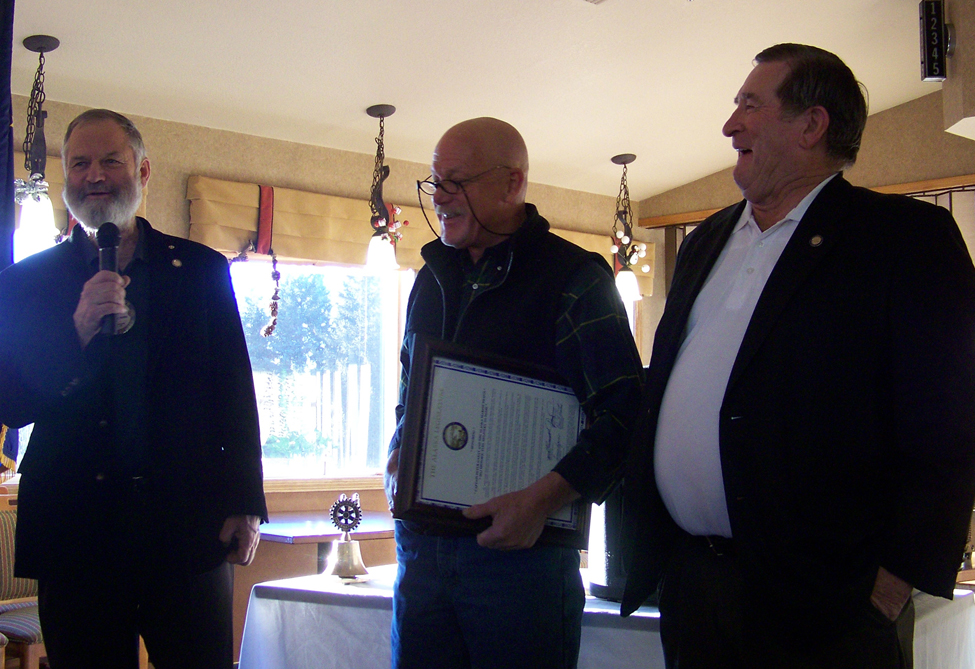

With Sen. Tom Wagoner, R-Kenai, on one side, and Rep. Paul Seaton, R-Homer, on the other, marine pilot Peter Garay of Homer received a legislative citation, accompanied by loud applause, during a meeting of the Rotary Club of Homer-Kachemak Bay on Dec. 20. The honor recognized the role of Garay and the Alaska Marine Pilots in the safe delivery of fuel to Nome almost a year ago, “the first historical winter marine delivery of fuel to Northwestern Alaska,” according to the citation.

Garay noted it wasn’t a one-person operation.

“It’s great being the guy (to get the citation), but there were a lot of other people that were every bit if not more involved than me,” he told the Homer News.

When severe weather kept a barge from delivering Nome’s winter supply of fuel in November 2011, concerns grew about community fuel tanks running dry. Those concerns were put to rest, thanks to the Renda, a 370-foot Russian tanker, and the USCGC Healy, a 420-foot cutter considered the United States’ “most technically advanced polar icebreaker,” according to information provided by the U.S. Coast Guard.

“From Dutch Harbor to Nome, Capt. Pete Garay of the Alaska Marine Pilots had a key role in the mission of the Renda. He served as the communications link between the Russian crew and the Healy. Once the tanker reached pilotage waters, he functioned as the compulsory state pilot and navigated the vessel through more than

360 miles of ice-packed seas,” the citation said.

How did Garay become the operation’s marine pilot?

“I volunteered,” said Garay, who has been piloting ships since 1990.

When discussions of the emergency fuel delivery began, plans were to back the Renda into Nome’s harbor to off-load the fuel. Beginning the voyage and arriving in Nome took longer than anticipated, a change that proved advantageous.

“Two to three weeks earlier would have been problematic to get in the harbor with the kind of ice that was forming,” said Garay. “By the time we got going, they did some ice sampling, drilled through some of the ice ridges out of the breakwater and discovered they went all the way to the sea floor.”

Garay boarded the Renda in Dutch Harbor at the start of its voyage to Nome, following closely behind the Healy.

For Garay, the best part of the operation was the decision-making process. As each player came to the table — a mixture of government, business and private individuals — the possibility of making a winter fuel delivery was uncertain. Those concerns eventually gave way to, “We’re going to do it.” Then came figuring out how everyone would participate.

“I’ve never seen an organization where everyone was so coordinated, pulling on the same oar,” said Garay. “It wouldn’t have been accomplished if it hadn’t been for everyone working together.”

Still, there will were moments of doubt and worry.

“I had a bunch of concerns about being with a loaded fuel tanker in the middle of the arctic,” said Garay. “Then I thought, just do the best you can. That’s what I came away with. You do your best and it will either turn out good, bad or in the middle. It was like Texas Hold ’Em. I was all in.”

While he never considered the conditions life-threatening, Garay was aware of the serious conditions.

“The first time we got stuck (in the ice), the compression forces on the ship were mind-boggling,” he said. “We came to a grinding halt and the ice floe started piling up on the side of the ship. The whole ship started throbbing and it sounded like a big tom-tom drum. That lasted for about five minutes and I asked the captain if it was normal. He looked at me and said, ‘This is normal for abnormal.’”

Garay was confident of Capt. Sergey Kopytov’s command aboard the Renda.

“He showed up on the bridge in Bermuda shorts, a T-shirt and flip-flops and I said, ‘Oh, this is good. This man is comfortable. He’s a pro. He’s been around ice breakers.’ If he was comfortable with the forces at work on the ship, I was comfortable.”

The Renda’s role in the fuel delivery is due to Michail Shestafov, supply manager for Vitus Marine in Anchorage. Born in the Ural Mountains, Shestakov has worked in the fuel industry since 1994, beginning with Far-Eastern Industrial Trading Company and Oldham International Ltd. From 1999-2006, he worked for the Aleut Enterprise Corporation, managing importing cargo to the fuel terminal in Adak.

“I’m Russian, so this kind of operation is not extraordinary,” said Shestakov.

For one thing, winter fuel deliveries are not uncommon in Russia. Secondly, Shestakov had relied on the Renda when he was working for the Aleut Enterprise Corporation and was friends with the ship’s owner. After Vitus Marine heard Nome was concerned about a fuel shortage, Shestakov called Bonanza Fuel in Nome

“I said, ‘Hey guys, if we come up with a solution, would you be interested?’ They said very much so. And that’s how it started,” said Shestakov.

While an activity of this type is “just a normal operation” in Russia, Shestakov was aware of its importance in the United States. Not only did the United States lack a ship equivalent to the Renda, certain Coast Guard procedures had to be addressed. For instance, one that requires a specific distance between two vessels had to be shortened to allow the Renda access open water created by the Healy.

“It had to be in really close proximity,” said Shestakov. “That was a major problem.”

Kopytov’s frustration over what he considered the Healy’s lack of ice experience led to a change of captains on the Healy enroute with the arrival of Jeffrey Garrett, a retired Coast Guard admiral with experience in Alaska, Antarctica and the Great Lakes.

While Garay considers Shestakov “the unsung hero” for putting together details of the Nome fuel delivery, Shestakov gives his vote to Kopytov.

“If anybody is the hero of the whole event, it’s the Russian captain,” said Shestakov.

After arriving in Nome, Garrett and Kopytov met face-to-face.

“The funny part was, Garrett worked as an ice pilot on cruise ships out of the Falkland Islands to Antarctica and Kopytov worked on tankers bunkering them,” said Shestakov. “They were there at the same time, but on different ships.”

In spite of the challenges and the overall success of the operation, Shestakov maintains his perspective.

“It may not be politically correct to say it, but I didn’t truly see much heroics. We just did our jobs. It’s nothing really extraordinary,” he said. “We didn’t walk into a house in a fire and save children, where you really have to make a decision. This was a routine job at the wrong time of year.”

As far as Garay receiving the legislative citation, Shestakov said, “I’m happy for Peter that he is getting this. For him, it’s a win-win solution.”

Part of the win is what Garay learned that can benefit the United States as activities in arctic waters increase.

“There’s a lot of folks in Washington that see the arctic as a little piece of pie along Alaska’s coastline that really has nothing to do with national policy, but I think people are getting educated as they see other countries positioning themselves globally to take advantage of the resources up there,” said Garay, who, in addition to continuing to pilot ships in Alaska, now serves on the Arctic Policy Commission.

McKibben Jackinsky can be reached at mckibben.jackinsky@homernews.com.