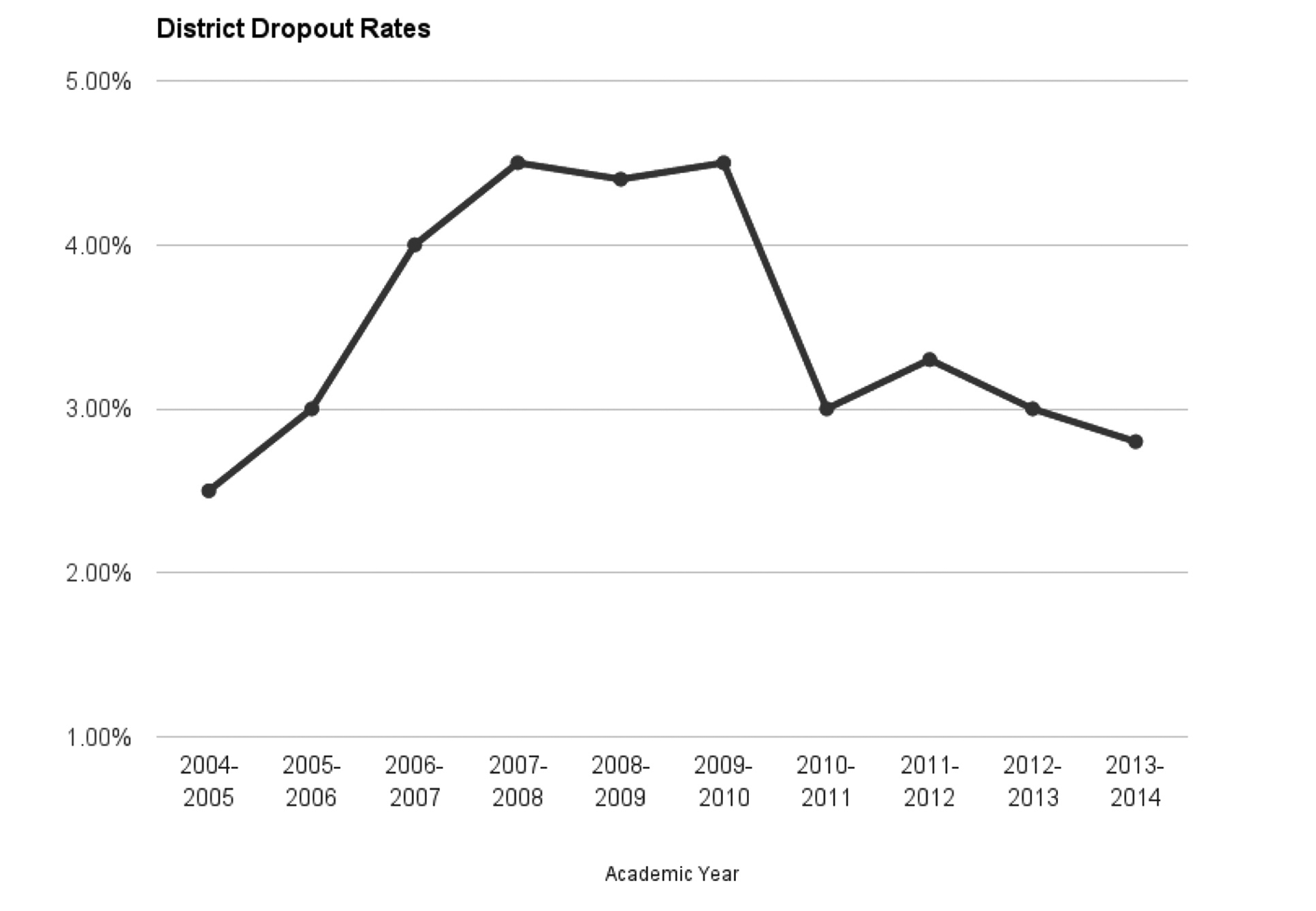

Kenai Peninsula Borough School District dropout rates have steadily declined for the past five years.

At the end of the 2013-14 school year, 2.8 percent of students in grades 7-12 dropped out district wide, according to the Alaska Department of Education and Early Development. The average between the end of the 2007 and 2010 school years was 4.3 percent.

The rate is also declining nationwide, and hit a record low at 7 percent, according to a 2014 report by the Pew Research Center.

“The decline in the count of (school district) dropouts is more impressive than the decline in the percent as enrollment throughout the district has declined in recent years,” said Tim Vlasak, director of K-12 schools, assessment and federal programs for the school district.

A number of support-based programs that target students at risk of dropping out have been in place in the school district for years, Vlasak said.

Programmatic staffing was introduced, which bumps the ideal 24:1 pupils per teacher ratio up by 15 percent, said director of secondary education John O’Brien in a previous Clarion interview.

“Intervention became a focus in grades 3-5, which pairs educators with struggling students, to complete a systematic approach of support,” Vlasak said.

The formation of alternative programs such as Kenai Alternative High School, Homer Flex and River City Academy offers students additional routes to take throughout their education and Connections Home School Program enables families to complete school together, he said

Last year 32 of Kenai Alternative High School’s 73 students dropped out.

The majority of students at Kenai Alternative are economically disadvantaged, said the school’s principal of six years, Loren Reese. The economically disadvantaged subgroup had the second highest dropout rate in the school district in 2014 at 4.1 percent, according to the Department of Early Education.

Students with limited English proficiency had a dropout rate nearly double the school district’s overall average in 2014, and male students are 1 percent more likely to stay in school than females, according to the Department of Education.

While Kenai Alternative’s dropout rate is significantly higher than the school district’s average, it has been dropping noticeably, Reese said.

Many of the students that enroll in Kenai Alternative are five or more credits behind to graduate, Reese said. Many are students in transition or out of state and need to make up credits that apply at other schools in the district, he said.

The school’s approach to keeping students in the classroom has been holistic, Reese said. Distance education in the form of online courses has offered students different ways to earn their credits, and the Afterschool Academy tutoring program has added assistance for learning material, he said.

Students can take classes on welding or construction through the Work Force Development Center located at Kenai Central High School, Reese said. It provides the opportunity to learn skills that are relevant after graduation, Reese said.

Establishing community partnerships has been imperative, Reese said. Groups from the Soldotna United Methodist Church, Our Lady of Angels Catholic Church and the River Covenant Church secure grant money and prepare breakfast at Kenai Alternative each week, Reese said.

“That’s a huge, huge thing,” Reese said. “Many students will tell you that’s their best meal of the day.”

Interested students are connected with the Kenai Job Center, which ensures a connection in the workforce before receiving a diploma, Reese said. Community mentors from the business community, and Kenai Mayor Pat Porter spends time working at the school, he said.

The dropout rates are higher in rural and remote areas where extracurricular and workforce related programs such as athletics and art programs are unavailable, Vlasak said.

“It’s not possible to offer all the same opportunities at a school of 30 students K-12 as a school of 300 students 9-12,” Vlasak said.

Tebughna School in Tyonek has many students that go to boarding school after eighth grade and are very successful, said Principal Marilyn Johnson.

“They participate in sports and other activities those schools offer, which we are not able to provide due to our small population,” Johnson said. “I call this a ‘Catch-22.’ We want students to remain in our villages, but we cannot guarantee a highly qualified teacher for each subject which leaves the only choice of online classes. They choose a boarding school to avoid the online classes and opt for the opportunity to socialize with others that they are not related to and have a teacher for each subject.”

Switching schools also creates barriers for students, Vlasak said. The school district has a high number of transient students.

“Research suggests that the greater the number of transitions (transfers), the greater the need for additional supports to be in place.”

It also makes it harder for the school district to track the student and can sometimes lead to decreased funding from the state, which is what keeps the support programs available Vlasak said.