In September 2014, the National Weather System sent out a false tsunami alarm, triggering tsunami warning sirens in Homer. As happened last Saturday in Hawaii when a technician clicked the wrong box on a program and sent out text alerts of an impending missile attack, the 2014 glitch also happened when a live code got sent out inadvertently.

With increased tension over a possible nuclear missile attack from North Korea, those events raise the question: Could a false alert of a missile attack be sent out in Alaska, and if so, how fast would it be corrected? Chances are slim that local authorities would send out a false message like the one that sent Hawaii residents into a panic, Dan Nelson, program manager at Kenai Peninsula Borough Office of Emergency Management, said.

“We’re confident that a similar event such as what happened in Hawaii won’t happen here,” he said.

Local emergency management agencies only have the authority to send out messages within their geographic jurisdictions, meaning any missile alert would have to get cleared on a state level before any related local warnings went out.

“The borough partners with the state and federal authorities for these types of warnings, but it would be very rare for the local office to send out something of this magnitude,” Nelson said.

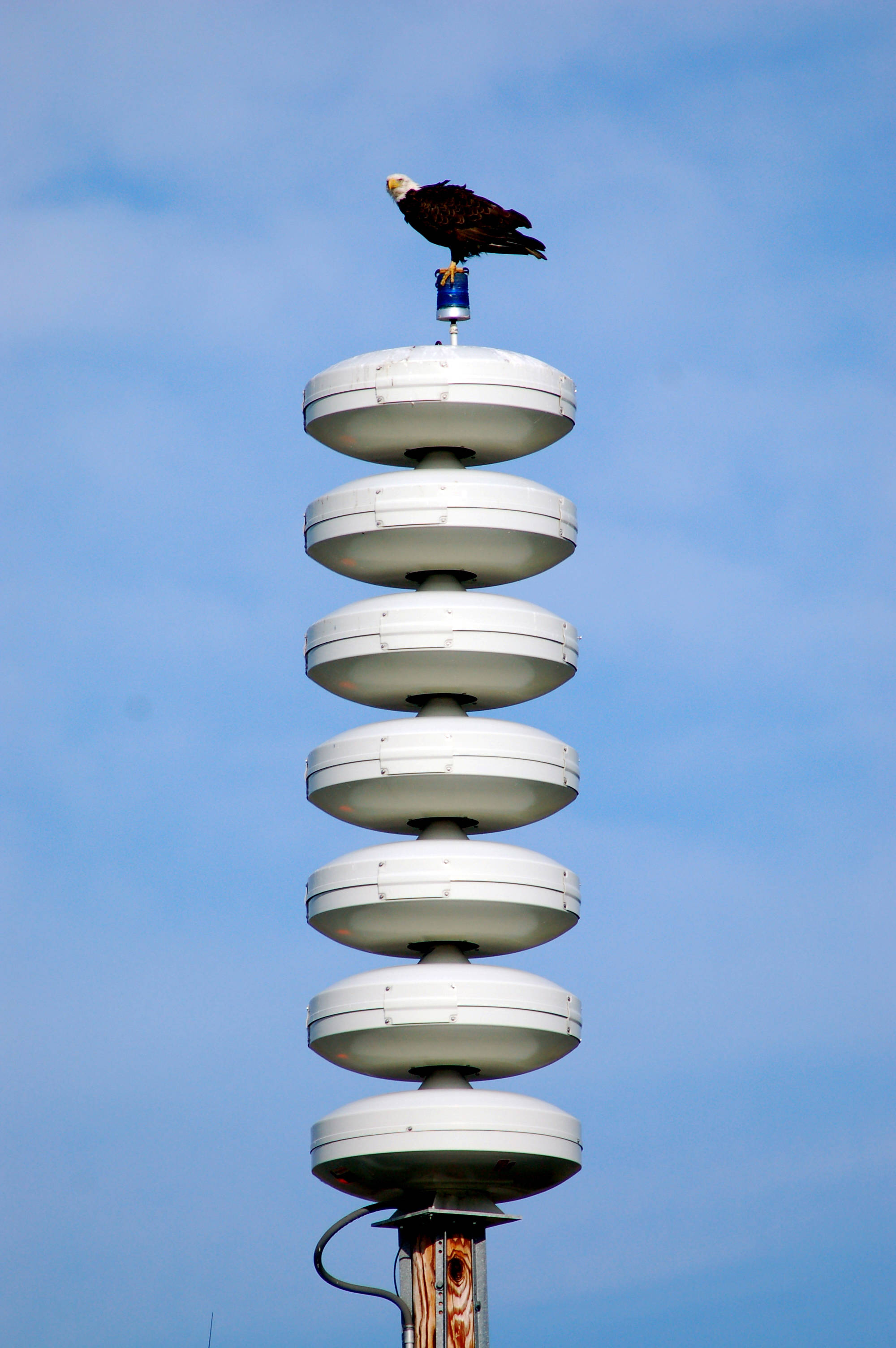

Homer Police Chief Mark Robl said local public safety officials can turn on the tsunami warning tower alerts manually and send out voice messages through the speaker systems. Visitors to coastal towns may notice the towers that look like stacks of flying saucers.

“If we got a message, say, from Homeland Security that says there’s incoming missiles, take cover, we would activate it locally if it hadn’t been done already,” Robl said.

That system also could be used to send out an “all-clear” message saying the alert was false.

Kenai Peninsula Borough Office of Emergency Management also doesn’t prepare templates or canned messages that can get sent out with a click of a mouse.

“Because the Borough is so large and there are so many potential incidents and variations of those incidents depending on location, we devise our messages when they are needed to ensure that local, pertinent information is broadcast,” Nelson said.

Similarly, tsunami sirens, which set off a panic in Homer in 2014 when they were mistakenly triggered, only go off automatically when a certain tone is broadcast through the emergency alert system, Nelson said. That was what happened in Homer: a live code sent out mistakenly during maintenance triggered a tsunami warning. Once emergency officials realized the error, they sent out a prerecorded message through the towers that said, “This is an all-clear. The test is now complete.” The false alarm caused a mild panic, and people on the Spit began evacuating.

The tsunami warning is tested in Homer at noon every Wednesday and starts with a four-note tone — the so-called Westminster chime, named after the clock tower in London.

Peninsula-specific emergency alerts are sent out via media, emergency broadcasting and through a Rapid Notify system that sends recorded voice and text messages to all landlines in the borough. Residents can sign up online to receive Rapid Notify messages on their cell phones as well.

KBBI public radio in Homer has a DASDEC unit, a brand name for an emergency alert encoder device programmed to monitor agencies which issue alerts on the Emergency Alert System, or EAS. If an emergency code is sent and the DASDEC picks it up, KBBI broadcasts the emergency message, said general manager Terry Rensel. KSRM radio is the primary radio responder for the entire peninsula, which KBBI monitors. KBBI also monitors the National Weather Service and the Alaska Public Radio Network.

On the state level, Rensel said agencies that can activate alerts include the State Emergency Operations Center at Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson and the Alaska State Troopers in Fairbanks.

“Any one of those upper operations could have done that,” Rensel said if a missile attack alert had been sent out in Alaska as happened in Hawaii. “There are so many place that have the authority on the statewide level to come in.”

Rensel cited another false alert that triggered the KBBI system several years ago. That was for a winter storm warning that should have gone only to Interior Alaska.

“It triggered the system down here. Whoever sent out the alert sent out the wrong codes and included the Kenai Peninsula,” he said.

In the event of a local emergency, Rensel said that KBBI wouldn’t wait for an alert to come through the tsunami towers.

“Quite honestly, in a situation like that, it’s quicker to break into programming and tell you what’s going on. Our system is set up to relay those things as quickly as possible,” he said.

In a statement, Sen. Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, said that after the false alarm in Hawaii, she is reviewing policies and procedures with the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the Alaska Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management “to ensure our current emergency alert plans are adequate to respond to a variety of threats.”

“I think we all can agree that we never want to see widespread panic due to a false alert, whether in Alaska or anywhere for that matter,” Murkowski wrote in an email. “… The Hawaii false alarm this past weekend also highlighted the need for the United States to continue promoting an end to North Korea’s nuclear program. Our way of life must not be held ransom by a foreign regime. I am proud Alaska is the cornerstone of our nation’s missile defense. Our military members based in Alaska continue to provide protection to our state, nation, and allies every day.”

Nelson stressed that residents shouldn’t rely exclusively on government alerts to find out about emergency situation. He suggested residents keep a battery-powered radio as a backup. Marine handheld VHF radios include channels for National Weather Service broadcasts.

While civil defense used to be geared more toward preparing for nuclear attacks, today the agency’s focus is on being able to respond to a multitude of emergency events, such as chemical spills, wildfires or flooding.

“We have not, as far as the borough is concerned, put together anything on the missile issue,” Nelson said.

Robl, a career cop who started as a Homer Police officer in 1984, said “In my lifetime here we have never interacted with the public at all in a nuclear attack scenario.” City emergency manuals don’t mention nuclear attacks, Robl said. Maybe that should change, he said.

“We’re in an era where this is something we should be talking about. North Korea, face it, they’re a threat,” Robl said. “If we’re entering an era we have to start talking about nuclear missile attacks — I hope to God we’re not, but it looks like we are — we should be updating our alert systems to accomodate that.”

Reach Erin Thompson at erin.thompson@peninsulaclarion.com and Michael Armstrong at michael.armstrong@homernews.com.