Jim LaBelle’s school days from 1955-61 aren’t fond memories.

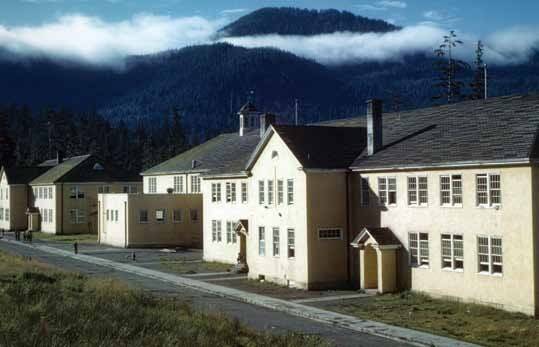

In those years, the Juneau man attended Wrangell Institute, one of Alaska’s boarding schools.

“The social workers basically forced my mother to make a decision to either give us up for adoption or send us to boarding school,” LaBelle said in a phone interview. “She didn’t really understand what she was sending us into. My brother and I were sent there when I was 8 years and my brother was 6.”

LaBelle was far from the only Alaska Native or Native American to have such experiences — or worse. Following the discovery of the mass graves of Indigenous children near a residential school in Canada, the U.S. has been reckoning with its own brutal history with the schools.

Some of the churches in Alaska, many of whom were affiliated closely or distantly with the residential schools, have issued statements, many urging further investigation of issues that have long been kept out of the public eye.

“Wrangell opened up the campus every fall to allow in the churches that were there in Wrangell, and we got parcelled out, often without our parents’ permission,” LaBelle said. “My mother was a Quaker, but there was no such animal in Wrangell, so we were assigned to the Southern Baptist church.”

While the Wrangell Institute itself did not have a direct connection to any particular church, Sheldon Jackson, who founded the Sheldon Jackson School in Sitka, was a Presbyterian missionary.

“The schools of Alaska are established, with but two or three exceptions, among a half-civilized people. It has long been known in educational circles that the greater the ignorance and the lower the condition of parents, the less they appreciate the importance of education for their children, and the greater the need of outside pressure to oblige them to send their children regularly to school,” Jackson wrote in a letter to Congress in 1886. “It is of no use to establish schools if the children do not attend, and many will not attend unless it is made obligatory on them.”

Many residential schools across Alaska were supported by various churches in the Lower 48, LaBelle said, some of whom have acknowledged their role, varying by region. Many were also sent out of state, including to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, where 13 Alaska Natives are still buried, LaBelle said.

“Every Sunday and every Wednesday we were forced to attend. There were no two ways about it. We were often punished if we were caught speaking our language at these events,” LaBelle said. “(The U.S.) government likes to pride itself on its separation of church and state, but it is often invited in these missionary schools. They were reimbursing these churches. That separation went out the window.”

The Presbyterian, Episcopalian, Quaker, Catholic churches, among others, had schools they supported across Alaska, according to Alaska History and Cultural Studies.

“Boarding schools attract pedophiles in places like Wrangell where I went. It also attracted pedophiles in all the mission schools. The Catholic Church was one of the biggest ones,” LaBelle said. “Catholic priests would molest kids not only in the schools, but in the villages as well.”

Records from the Alaska State Archives state the rates of physical, mental and sexual abuse were highest among Christian-operated schools.

“Some of the churches like to say they were more benign, that they treated the Natives better, with a sense of pride. False pride to my mind. I think they were some of the churches that did the most damage,” LaBelle said. “When these church groups came to Alaska to give us the word of God and everything, they brought their European cultural ways, which was in contradiction to Indigenous cultural ways.”

Bringing past deeds to light

As the sins of the past are dragged out where everyone can see them, some churches have issued statements acknowledging their role, and calling for members of their congregations to listen to the experiences of Indigenous people hurt by their churches.

“The discovery of graves on the grounds of former boarding schools in Canada has torn open the wounds of historical trauma in the lives of Indigenous and Native people across this land and confronts the Church with its legacy in this trauma,” said Bishop Mark Lattime of the Episcopal Diocese of Alaska in a news release. “Our Native Alaskan brothers and sisters have too long carried the weight of historical trauma from our nation’s policies of assimilation. For too long, the Church has hidden its face in shame or chosen to ignore its complicity in the cruelties of assimilation and eradication of indigenous cultures.”

The Episcopal Church made a number of resolutions with the announcement, including supporting truth and healing commissions, making reconciliation a focus of the church’s executive council and 80th General Convention, spending more time with Indigenous people and listening and learning how they can help heal relationships and commending Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland for her establishment of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative.

The FIBSI is a review of the legacy of federal policies concerning the boarding schools operated nationwide.

“The Interior Department will address the inter-generational impact of Indian boarding schools to shed light on the unspoken traumas of the past, no matter how hard it will be,” said Haaland in a news release. “I know that this process will be long and difficult. I know that this process will be painful. It won’t undo the heartbreak and loss we feel. But only by acknowledging the past can we work toward a future that we’re all proud to embrace.”

Other churches asked that those with concerns about their treatment in the church-operated schools bring them to the church in question’s governing body.

“The Archdiocese of Anchorage-Juneau recognizes the trauma that this reporting has caused to many of our Native Alaskan brothers and sisters. The Archdiocese of Anchorage-Juneau welcomes those impacted by these stories about residential schools to seek comfort and refuge from our parishes and ministries across the Archdiocese,” said John Harmon, chancellor of the Archdiocese of Anchorage-Juneau in an email. “The Archdiocese also encourages anyone with concerns about the residential schools that were formerly part of the former Archdiocese of Anchorage or the former Diocese of Juneau to bring those concerns to the attention of the Archdiocese of Anchorage-Juneau.”

The Presbyterian church disavowed its earlier teachings in a 1991 statement, wherein they state their church’s belief that abandoning Native culture was a prerequisite for Christian was wrong. The statement also states the church’s regret for destruction of Native artifacts and its role in the loss of Native languages.

“We further call upon all members of our churches to pray and work for reconciliation between the peoples and cultures of our region and bring to an end the misunderstanding, especially of Native cultures, mentioned above,” reads the Native Culture Resolution of the Alaska Presbytery.

While the Alaska Presbytery, which has since been folded in the Presbytery of the Northwest Coast, was not part of the body that now governs it, the Northwest Presbytery is now looking more closely into the role the church played in the residential schools in Alaska said executive presbyter Corey C. Schlosser-Hall in an email.

“Even some of the church groups are starting to acknowledge the role they played,” LaBelle said. “They’re discovering these kids that are buried in so many residential school grounds, not just across Canada, but across the United States as well.”

Contact reporter Michael S. Lockett at (757) 621-1197 or mlockett@juneauempire.com.