What would Brother Asaiah do?

That question is at the heart of a dilemma many small cities would love to face. Where’s the best place to put a donation of an $18,500 work of art by one of Homer’s finest sculptors?

The issue will be on the agenda of the Homer City Council Monday night when the council considers a resolution to accept a sculpture of Brother Asaiah Bates to be done by Homer artist Leo Vait.

Brother Asaiah, who died in March 2000 at the age of 78, was “perhaps the closest thing Homer will ever have to a patron saint,” Homer News reporter Hal Spence wrote of him in an obituary. Brother Asaiah also was a Homer City Council member.

The council will consider two things:

• Should the city accept the Brother Asaiah sculpture into its art collection?

• Should the sculpture be installed on a rock at WKFL Park, the land Brother Asaiah gave to the city of Homer?

Both the Public Arts Committee and the Parks and Recreation Advisory Commission have recommended accepting the art work. The Public Arts Committee at a Jan. 9 special meeting passed a resolution saying that the statue would be acceptable to the city collection.

“However, there is a question regarding the location being appropriate and therefore recommend the city council hold a public hearing on the issue,” the resolution also said.

The Public Arts Committee passed the art donation request on to the Parks and Recreation Advisory Commission. At its meeting last Thursday, parks and recreation agreed with the art committee and forwarded the question to the council.

Many people who knew Brother Asaiah agree that it’s OK for the city to accept the art work. They disagree on putting the statue in WKFL Park.

“I’m a libertarian. I don’t care if somebody builds a sculpture. They can do anything they want,” said Michael Kennedy, a friend of Brother Asaiah. “When it goes into the public domain, then it becomes different.”

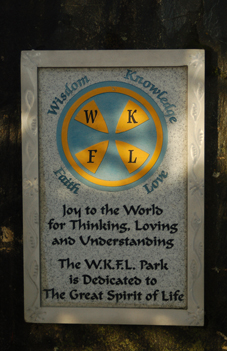

“WKFL” stands for “Wisdom, Knowledge, Faith and Love,” according to a plaque on a large boulder in the park, but it also stands for “Wisdom, Knowledge, Faith, Love Fountain of the World,” the name of the organization known as “the Fountain” and its followers as “the Barefooters,” for their practice of walking barefoot even in winter. It was the reason Brother Asaiah came to Homer in 1958. Born Claude Bates in 1921, Brother Asaiah got his name from Krishna Venta, founder of the Fountain. Venta led a group to Homer where they settled in the Fox River Valley. The movement faded away after Venta was killed in a bomb explosion in California in 1958, but Brother Asaiah and a few others remained in Homer.

In the 1960s when a generation of hippies and back-to-the-landers came to Homer, Brother Asaiah became something of a guru to them — a Greatest Generation World War II veteran who wore a beard and long hair in a ponytail and called everyone “brother” and “sister.” Brother Asaiah preached and lived a life of tolerance and respect, and became an unofficial ambassador between the generations of Homer residents.

“He was always the big reconciler,” said Brad Hughes, a friend of Brother Asaiah and a Homer artist. “His big gift to the community was he achieved likability and respect between old-time homesteaders, hippies and the fishing community.”

A fellow Barefooter, John Nazarian, commissioned Vait to sculpt the statue, a waist up representation. Vait will receive $8,000 in artist’s fees and also be paid for site preparation and installation. Vait said it will cost another $7,000 for a foundry to make the mold and pour the bronze statue. Other costs include shipping, signage and site preparation. A spotlight will illuminate the sculpture to guard against vandalism.

Vait said Brother Asaiah posed for him at a 1996 Putting on the Ritz Pratt Museum fundraiser knowing that his image might be out in the public. Brother Asaiah had one stipulation, Vait said.

“‘You be sure and put the ponytail in,’” Vait said Brother Asaiah told him. “That doesn’t sound like someone who doesn’t think he wouldn’t want his image out in public.”

Will Files and Martha Ellen Anderson, author of “Brother Asaiah,” a biography of him and a collection of his letters, are acting as Nazarian’s agents.

“Newcomers have not experienced his presence first hand, and sometimes even we sourdoughs forget. I give this statue to renew his loving spirit,” the public art application reads. “My wish is that this great work of art depicting his pain, peace, joy and transcendent love, can rekindle that loving spirit which Brother Asaiah gave to us in our ‘Cosmic Hamlet by the Sea.’ What better place than the WKFL Park.”

Some would disagree with that.

Hughes and Kennedy were part of a small group of friends who fulfilled Brother Asaiah’s burial wishes. Brother Asaiah himself laid those out in a letter he wrote to the Homer News in the fall of 1999. He said that he believed unseen midwives assist the soul in its transition from life to death. He explicitly said he wanted his body left untouched for three days and three nights, and then placed in a strong cardboard box for burial wherever.

“The location does not matter. Whoever places the body in the earth, walk away and never look back,” Brother Asaiah wrote.

Hughes, a former minister, talked often with Brother Asaiah about his spiritual philosophy. He said Brother Asaiah did not want anyone to reveal where he was buried so no one would pay attention to his remains.

“He believed that when people made a fuss about you and prayed over you, it attracted you back to the earth plane drama,” Hughes said.

“People warned him that to put energy out there would pull him back,” Kennedy said. “He wanted to be free to go on.”

Putting up a public sculpture in a park on land Brother Asaiah owned, but that he did not give his name to, would go against that belief, Hughes said.

“It’s totally against the whole spiritual picture he wanted to live by,” he said.

“He didn’t want a tombstone, a headstone,” Kennedy said. “Putting his head on a rock in the middle of town is kind of like a tombstone to me.”

The idea of a WKFL statue did get support from former Homer mayors Jack Cushing and James Hornaday, both of whom wrote letters backing the idea.

Ken Landfield, another friend of Brother Asaiah, said he thinks the question of where to put the sculpture should have a wider community conversation.

“Everybody’s first reaction is ‘What a great idea. Do you think Brother Asaiah would have wanted that? Hmm, I have to think about that,’” Landfield said.

Hughes also said he doesn’t like the idea of bronze sculptures to honor dead people. Hughes was commissioned to build a Jean Keene memorial to the woman known as “the Eagle Lady.” He said he’d do it if it wasn’t a statue. Hughes built a bench out of what he calls “beach concrete,” a concrete, seashell and beach stone composite. It has a plaque on the back showing several of the eagles Keene fed.

Everyone who spoke about the issue agreed on one point: It’s tricky to try to guess Brother Asaiah’s intentions.

“We’re all walking on a slippery slope when we’re talking what his wishes were 25 years ago,” Vait said. “Since he didn’t leave any record about the sculpture in particular, we’re speculating pretty much.”

His friends and supporters also agreed on another point: Brother Asaiah wouldn’t want people to get in a shouting match and be angry with each other. In his last letter, Brother Asaiah himself said, “Please be kind to each other. Love one another.”

“There is agreement there should be a wider discussion of this matter,” Landfield said. “I think this town should talk about it. Whatever this town decides, I’ll be OK with.”

Vait said he it would be fine if the sculpture went to the Pratt Museum.

“It doesn’t really matter to me where it goes,” he said.

“I think maybe they should put his bust in City Hall, right back there where he used to sit,” Kennedy said.

Hughes had another idea for honoring Brother Asaiah.

“If you want to have a memory of Asaiah, load up a truckload of food and take it over to the food bank, or make a scholarship to a high school student,” he said.

The council could decide to hold a public hearing on the resolution and postpone action. The sculpture won’t be poured until the council approves accepting it. Vait has prepared a maquette, or small sculpture, as a study, and is working on the full-scale sculpture that would be used to make the bronze statue. If approved, it would be finished by May 2014.

Michael Armstrong can be reached at michael.armstrong@homernews.com.