Alaska’s economy and demographics are changing. Declining revenues have serious long-term implications for local government.

Underlying causes — the oil industry decline and the graying population — are more pronounced for the Kenai Peninsula than for the state as a whole. While the city of Homer is pursuing its “Closing the Gap” project to solicit citizens’ ideas on economizing, the Kenai Peninsula Borough, too, is launching a comprehensive review of its tax code.

The review is intended to modernize the code, root out inconsistencies and examine problem areas. It will include scrutiny of the revenue streams the borough can influence — sales and property taxes. One aspect sure to attract attention is the trend over the past generation to exempt homeowners from property taxes and shift the burden of paying for services elsewhere.

Kenai Peninsula Borough Mayor Mike Navarre tapped his special assistant, Larry Persily, who has prior experience working with the Alaska Department of Revenue, to manage the review. Borough staffers will meet next week to plan the review and delegate its initial tasks.

Persily said the mayor decided this is an appropriate time to review tax-code provisions to see if changes are needed. The review is not designed to eliminate exemptions or raise taxes, he stressed, but is an open-ended process focused on the fiscal future.

“It’s really the proverbial blank sheet until we start reading through them,” he said.

The review’s timeline has yet to be established. It will include public meetings to seek input in communities around the borough, most likely during the winter months, he said.

Factors in the borough’s budget squeeze include a decline in state funding, an increase in tax exemptions and projected declines in the oil and gas economy. The only one of those the borough can influence is exemptions.

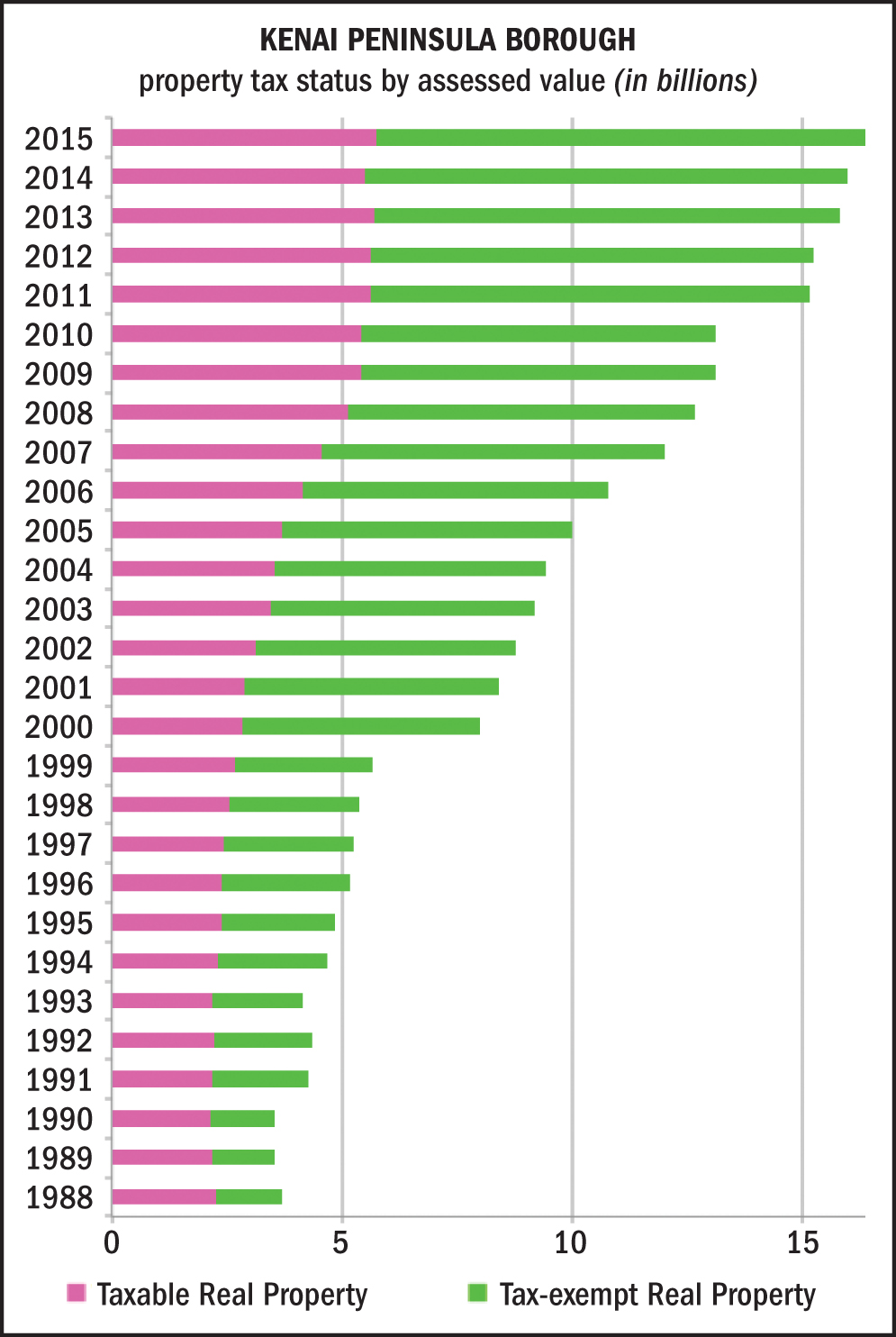

About half of the borough’s revenue comes from property taxes, mostly from real estate. The borough uses that revenue to fund schools, roads, hospitals, ambulances and firefighting. Land and improvements in the borough are assessed as worth about $16 billion, according to the current parcel database. But about two-thirds of that real property is now exempt from taxation.

Taxes are always unpopular and controversial. Conversely, voters love exemptions. Many exemptions are mandated by state or federal laws that the borough cannot alter, but an increasing number are options chosen by borough voters or assembly members.

For the current fiscal year, the exemptions for real property cost the borough’s general fund about $48 million. Of that total, about $4 million is due to local option votes.

By far the largest exemption is mandated for government land. The borough does not tax itself or the peninsula’s incorporated cities. But it cannot tax state or federal land either. The federal government owns about two-thirds of land within the borough; the state owns about one-fifth. In the current fiscal year, which began July 1, about $7.8 billion worth of government land is exempt from borough property taxes.

The borough budget estimates that the exemption on government lands is equivalent to about $35 million in lost property tax revenue annually.

The state does not reimburse the borough for lost tax revenue. The federal government has a program, Payment in Lieu of Taxes or PILT, that pays the borough, but it is disconnected from property tax assessments, said Craig Chapman, the borough’s finance director. Congress decides whether to pay all, some or none of the designated PILT, set up as an allowance per acre, now 36 cents. The PILT has been fully funded for the past five years, adding up to about $2 million annually, he said.

Another mandated exemption is for Native lands. It covers Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, or ANCSA, real estate belonging to tribes and Native corporations, which adds up to about 9 percent of borough land, and also the much smaller category of Native allotments. The Native exemption affects about $4 million in potential property-tax revenue a year, and the borough receives no compensation for that.

Other mandated tax exemptions affect property owned by veterans, charities, religious entities and the Alaska Mental Health Trust, as well as land used for cemeteries, hospitals, electrical cooperatives, public housing, public education and senior centers.

Recent past trends and future projections suggest the exemptions will continue to grow faster than revenues and erode the borough’s finances. The seniors’ and homeowners’ exemptions are controversial.

Exemptions for senior citizens (and disabled veterans) combine state mandates and borough options. These exemptions have complicated histories dating back to the 1970s, when the borough offered a $250 discount on tax bills to those who qualified.

In the 1980s the state legislature mandated that local governments exempt $150,000 of a senior (age 65 or more) citizen’s primary residence’s assessed value from property taxes. Kenai Peninsula Borough voters opted in 1986 to go beyond the state and exempt the total value. The state initially reimbursed boroughs for the mandated portion, but as oil revenue dropped the reimbursement rate fell and, in 1997, ceased.

After reimbursements ended, the fiscal problem the exemption created for the borough became severe enough to prompt revisions. In 2006, the assembly voted to limit the exemption to residents only, as defined by eligibility for the Alaska Permanent Fund Dividend. Then borough-mayor John Williams told the assembly that the lost tax revenue had risen from about $130,000 a year in the 1980s to more than $4 million. The following year, borough voters agreed to cap the senior exemption at $300,000.

A separate hardship exemption exists for seniors who can’t afford to pay their property taxes. Currently, six parcels qualify for that status, said Tom Anderson, the borough’s chief assessor.

Even with the restrictions, the Kenai Peninsula’s senior exemption is unusual.

“The borough has the highest senior exemption (in value) in the state,” Chapman said.

Over the past few decades the number of young adults in the borough fell, while the senior population mushroomed. Factors include the aging of the baby boomers, an exodus of young people seeking better job opportunities elsewhere, a tendency for aging residents to stay due to better medical and other support services, and retirees moving to the peninsula due to its charms and — yes —tax breaks. Since 2010, about 200 new households a year are signing up for the senior tax exemption, which now benefits more than 4,000 households.

The separate exemption for homeowners of all ages also rose. In 2004, after state legislation allowed for higher exemptions, borough voters raised the residential real property exemption from $10,000 to $20,000. In 2012, a statewide ballot measure allowed municipalities to raise that to $50,000. In 2013, a successful initiative on the borough ballot raised the Kenai Peninsula Borough homeowners’ exemption, effective for the 2015 fiscal year. About 10,000 households use that exemption.

The increase in the homeowners’ exemption led to $300 million worth of assessed real estate moving to tax-free status in 2014. Even without that surge, about $50 million of land moves off the tax rolls each year due to charitable and local-option exemptions, according to records provided by the assessors’ office.

The various exemptions add together rather than overlap. Because the senior exemption is only available for a primary residence, such a property also is eligible for the $50,000 homeowners’ exemption. That means the real maximum for seniors is $350,000, not $300,000.

“Yes, they do stack on top of each other,” Anderson said.

Back in the mid 1990s, the amount of exempt real estate first surpassed the taxable amount. Ever since, the faster pace of exemptions has widened the gap, leaving a smaller percentage of borough land on the tax rolls with each passing year. In 1990, 61 percent of the assessed land value was taxable. In 1995, the percentage was 49. The decline continued except for a brief uptick when the rules on the senior exemption were tightened. In 2015 the taxable portion was 35 percent.

This adds up to an unintended experiment as the tax burden shifts away from senior citizens and homeowners to others.

“It causes a tax increase for everyone else,” Anderson said.

Those left to shoulder the tax burden include renters, working-age residents, business owners and non-resident landowners.

Mako Haggerty, outgoing assembly representative from the southern peninsula, said he worries about young families carrying too much of the burden. He and other borough officials said that the state’s rules and lack of reimbursements stick local government with unfunded mandates. The situation brings up difficult questions about who funds government, who can afford it and how can responsibilities be distributed fairly.

Shana Loshbaugh is a researcher and writer who lives on the southern Kenai Peninsula.