At a meeting and public hearing Thursday night, the Homer Public Arts Committee didn’t just reject the idea of putting a bust of Brother Asaiah Bates in WKFL Park. It recommended not accepting into the city art collection at all a proposed donation of the $18,500 bronze bust.

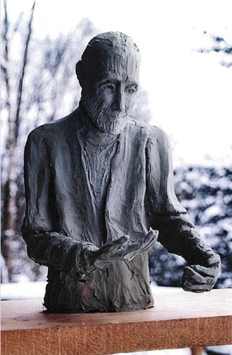

John Nazarian, a friend of Brother Asaiah, planned to commission a sculpture by Homer artist Leo Vait to be cast as a bronze statue and placed on the rock in WKFL Park.

Nazarian, 76, is an Armenian immigrant born in Syria who met Brother Asaiah when he lived at the WKFL compound in 1962 and was going to the Pasadena Playhouse, a theater school. Nazarian said he didn’t mean to create a problem in wanting to donate a statue of Brother Asaiah.

“It was for my love and respect for him and for the Cosmic Hamlet by the Sea,” Nazarian said in a phone interview on Monday from his home in Los Angeles. “Whatever they decide, I with reverence and love accept it.”

In a letter to the committee, Vait said Nazarian’s donation “is not a pot of money up for grabs, but a generous donation specifically allocated to create a bronze bust.”

The recommendation goes to the Homer City Council for its consideration. It will be on the March 24 meeting agenda. The council had considered previous recommendations from the Public Arts Committee and the Parks and Recreation Commission to accept the statue. Both bodies balked on the issue of where to put it.

The council sent the matter back to the Public Arts Committee.

Brother Asaiah made a partial donation to the city of the lot at the corner of Pioneer Avenue and Heath Street. The name of the park means “Wisdom, Knowledge, Faith and Love,” and refers to the Wisdom, Knowledge, Faith and Love Fountain of the World, also called the Fountain. Started in Simi Valley, Calif., in the late 1940s by Krishna Venta, WKFL came to Homer in 1957 to establish a branch on 480 acres of land in the Fox River Valley at the head of Kachemak Bay.

The group was known as the Barefooters for their practice of going barefoot, even in winter. After Venta was murdered in a suicide bomb attack in 1958, the Fountain eventually faded away in Homer in the early 1960s and the late 1960s in California. Some Barefooters like Brother Asaiah and Helen and R.B. Jackson became part of the Homer community.

At a public hearing Thursday night, six people spoke, all against the idea of putting a statue in WKFL Park. Some raised separation of church and state issues, with concerns about WKFL being a religious organization.

In an interview for a Jan. 30 Homer News article on the park, Jackson described WKFL as a humanitarian service group and not a religious organization. Nazarian said that after the Fountain ended, he and Brother Asaiah didn’t intend to create a religious thought or organization.

“But I do believe in the four words: wisdom, knowledge, faith and love,” Nazarian said.

Linda Jones expressed concerns about WKFL’s spiritual aspect. “Regardless of anything, WKFL was a religious organization,” she said.

Others said at the meeting that they felt a statue would go against Brother Asaiah’s wishes. A few referenced an opinion piece published in the Homer News by artist Brad Hughes about the relevancy of personal statues.

“I’m very opposed to that being put actually anywhere in the city,” said Troy Jones. “I don’t think it was his (Asaiah’s) wishes.”

Ray Kranich said he agreed with Hughes. He said he thought the issue of personal memorials was settled by the city when the council decided not to put a memorial to Jean Keene on city land on the Spit. Hughes eventually designed and made a memorial bench to Keene that’s at Land’s End Resort.

“You’re going to open a big bag of worms when you start putting personal memorials on city property,” Kranich said. “You wouldn’t have room in that park for a bench.”

Michael Kennedy, a friend of Brother Asaiah who with Hughes helped bury him, said, “That was true, the sentiment — don’t look back,” referring to Brother Asaiah’s burial wishes that once he was placed in the ground people turn away.

Arlene Ronda agreed with Hughes’ opinion, too. Hughes wrote that Brother Asaiah believed in “that transitory experience of the individual life and the universal presence of the divine in all, not just a special few.” Ronda mentioned that quote.

“I do think that we honor Asaiah for that reason, for his humanity and for his existence, that he sees the good in other people, that we respect one another. That’s why I’m here,” Ronda said.

Kennedy also said he thought there might be some constitutional issues.

“Maybe the city erred in accepting this property, to take the property and name it ‘WKFL’ and that it has a religious connotation,” he said.

In response to the idea of Brother Asaiah’s religious associations, Andy Haas, also a friend, called him “a joyful, spiritual man.”

“When I knew him, he attended just about every church in town, and he attended them joyfully,” Haas said.

Paul Hueper mentioned an association between WKFL and notorious murderer Charles Manson and said that merited a closer look. “There’s some bad history there,” he said.

Nazarian said Manson and his group lived near the WKFL group in California, and that Manson sent some of the women involved with him to stay at WKFL. Manson also visited. “Charles Manson never lived there,” Nazarian said. “No association.”

Billy Choate had written an opinion piece describing his abuse by a follower of Venta when Choate was a teenager.

“I had dozens and dozens of calls and emails from people who feel the same way I do, that it’s not a place for a bust,” Choate said at the hearing.

Ken Landfield, also a friend of Asaiah, has been following the issue since it first came up at the Public Arts Committee.

“The reasons I stirred up this pot, I think we should have this conversation,” he said. “If the statue were to go up without this conversation, that would be painful on a lot of levels.”

Nazarian said he will still commission Vait to create the statue of Brother Asaiah. “If nobody wants it, I will bring the statue in my backyard and have a glass of Scotch, a pickle and a pretzel,” he said.