Birders visiting Homer for the Kachemak Bay Shorebird Festival this weekend may hope to see a rare bird or one new to them — a “lifer,” as they’re called. In April 2016, Anchor Point bird watcher Steve Friend found the ultimate lifer: the tracks of shorebirds preserved in a slab of rock millions of years old.

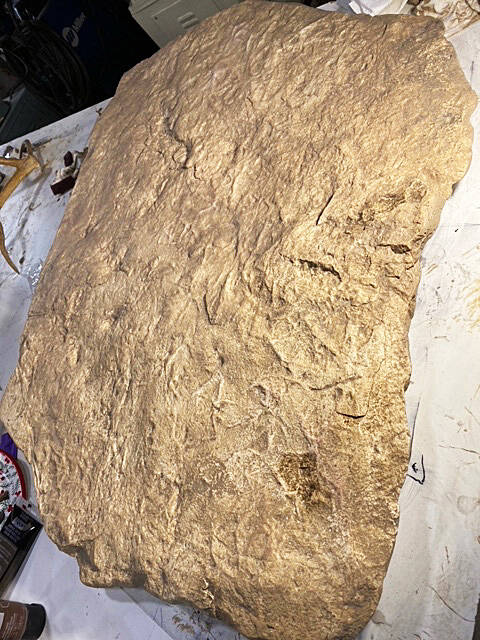

For the shorebird festival, a cast of Friend’s find will be displayed at the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge headquarters. Tracks of two different species crisscross the rock, the sort of tracks shorebirds make when they feed in habitat like that of Mud Bay on the Homer Spit, prime viewing for shorebirds this weekend.

Friend said he noticed the fossil tracks in a slab of rock about 3-feet wide by 4-feet long while walking the Anchor Point beach at an extreme minus tide with his grandson a few miles east of the Anchor River. Storms can expose rock that then can be seen at low tides.

“My grandson and I were walking along the beach and looking at rocks for fossils in general,” he said. “We happened to see one where the surface looked weird. … I stopped and changed my angle a bit — looking at different angles of it — and finally convinced myself what I was looking at.”

The tracks are of several different sizes and number at least 100, Friend said.

“It appears to be shorebird type birds,” he said. “Nothing like ducks or gulls or anything like that.”

Local fossil expert Janet Klein, who helped get the cast displayed, said she hopes visiting birders might offer some clues on what modern species the ancient tracks might resemble. Klein said the fossil tracks date to the Miocene period from 5-23.5 million years ago. It’s possible they’re from the same time period as a tapir fossil her grandson found that dates to 9-10 million years ago, she said.

After Friend found the fossil tracks in the rock slab, he took photographs, noted its location, and sent the photos and information to Pat Druckenmiller, a University of Alaska Fairbanks paleontologist and director of the Museum of the North.

“Am I seeing what I think I’m seeing?” Friend said he wrote Druckenmiller. “I think these are foot tracks, and if they are, would you be interested in seeing them?” Druckenmiller quickly replied “Yes.”

Because the fossil was in state tidelands and by law any vertebrate fossils on state land belong to Alaska, Druckenmiller had to get a state permit to collect them. Because of the risk that storms could again bury or damage the tracks, Druckenmiller asked for a quick turnaround on a permit. Within a few days he got a permit and he and a crew drove to the fossil site to collect the rock.

Friend said it took about three hours to wrestle the rock into the back of a pickup truck. They had to place plywood under the slab and winch it into the truck on ramps. The original fossil rock now is at the Museum of the North, and Druckenmiller made a study cast that the shorebird festival displays.

Klein said Ellen Jakovich painted the cast to more closely resemble the material of the original fossil. Klein thanked her neighbor, John McLean, for letting them use his shop while preparing it for display.

Druckenmiller told him that there has been only one other set of tracks from the Miocene found in the state — a pretty rare bird, indeed.

“They were really excited about seeing them,” Friend said of the paleontologists.

Reach Michael Armstrong at marmstrong@homernews.com.