If you built a raft with a big sea anchor and pushed off from Point Pogibshi, you’d drift east along Kachemak Bay on the south shore, turn left at the Homer Spit and eventually circle around the north shore and go west toward Bluff Point, spinning back around in a big gyre.

Or, maybe not. You could wind up at the head of the bay. You could be pushed out into Cook Inlet. In a big storm and tide you could get washed up on the beach.

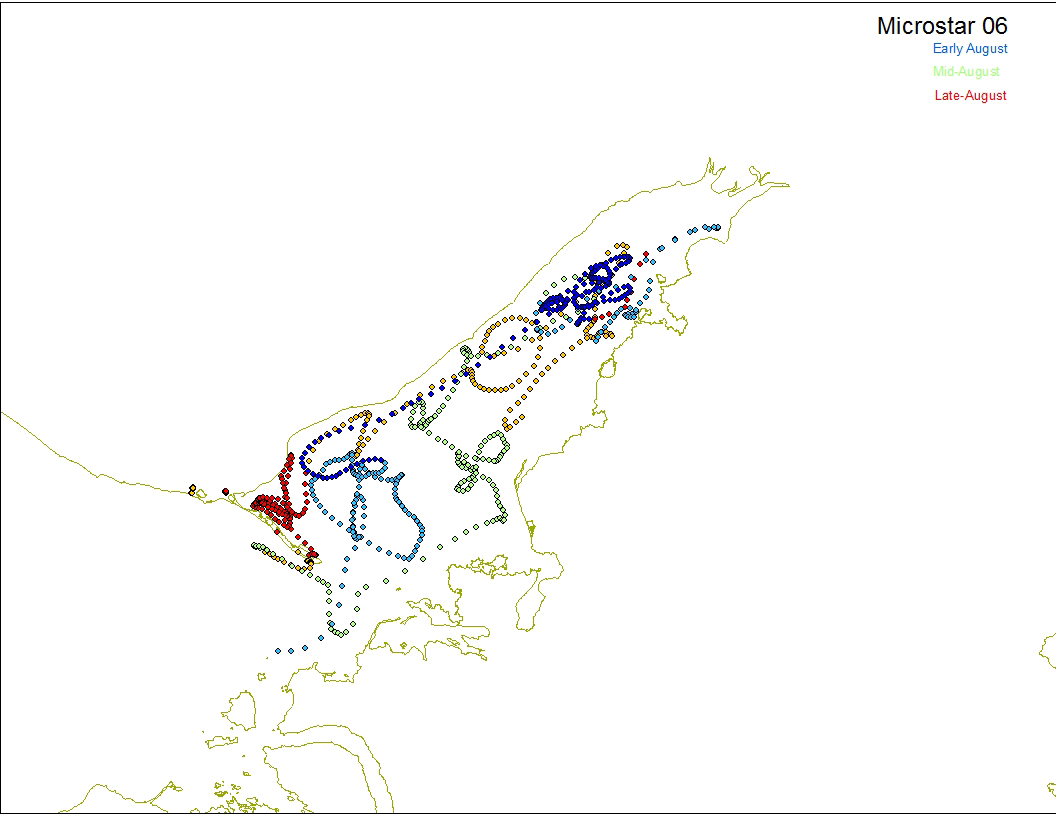

How long something — rafts, larval crabs or spilled oil — would take to circle the bay and where it would go are some of the questions being studied by a two-year ocean circulation project done by the Kachemak Bay Research Reserve and the University of Alaska Fairbanks Institute of Marine Science. On Monday at noon and 6 p.m., scientists present some of their findings at the Alaska Islands and Ocean Visitor Center. Another presentation is at 6:30 p.m. Tuesday at the Seldovia Library.

Drift studies have been done before, but those involved numbered cards dropped into the bay. Because the cards floated on the surface, they were affected both by ocean currents and winds. The new study looks at sub-surface currents, the forces that move kelp, seaweed, young crabs and other plankton at the mercy of tides and currents. The effect on crabs is one reason to do the study, said scientist Steve Baird of the research reserve.

“Circulation patterns are very important for a lot of things, but especially for moving larval fish and crabs around,” he said. “Larval fish are basically planktonic.”

Since April of 2012, Baird and other scientists have been setting loose in the spring and summer small buoys with satellite tracking transmitters. Surface drifters, a red-and-white 10-inch wide buoy, have a 3- to 6-foot long drogue — essentially, a big underwater sail — that catches the upper currents. The deep drifters are black and 18-inches wide and have a drogue about 50-feet long to catch deeper currents.

“What’s really moving them around is that underwater drogue, whatever depth it’s at,” Baird said.

Both types of drifters can be tracked on a password-protected website. That’s the science — seeing where the drifters go at certain times of the year related to tides, storms and other forces. Tracking the drifters by satellite also helps them get found when they get lost.

“They get picked up by people or end up on a beach,” Baird said. “Sometimes they end up being souvenirs.”

Researchers found one such drifter far from Kachemak Bay and tracked it to a cabin on Petersville Road near Talkeetna.

If found drifting in the bay, Baird said mariners should let it wander in the water. If found washed up on the beach, usually from storms or an extreme tide, people should pick up the drifter and return it to the research reserve offices at the Alaska Islands and Ocean Visitor Center or call 235-4799.

People have been generally supportive of the study, Baird said.

Figuring out the currents of the bay will help biologists better understand life cycles of things like Tanner and Dungeness crabs. One theory for why Kachemak Bay’s crab populations haven’t recovered from overfishing is that the local adult population was depleted and juvenile crabs pushed in from other areas by currents also get pushed out. The general bay circulation pattern is a gyre spinning counterclockwise looking north, with the south shore current running east and the north shore current running west.

The study also will help predict where things like invasive species or oil spills might wind up in Kachemak Bay. The research also can be used for search and rescue to find mariners lost at sea and floating in life rafts or survival suits.

“I think there are all sorts of benefits for understanding the circulation patterns of the bay,” Baird said.

The current turns somewhere off the end of the Spit, but some drifters have gone into the inner bay. Scientists know that can happen to things like bull kelp, which has been found at the head of the bay.

There’s a bit of chaos to the pattern, though. Side bays like Sadie Cove and Tutka Bay have their own patterns which can affect the larger bay. Currents from outflow like glacial runoff affect the circulation pattern, as do lower Cook Inlet and upper Cook Inlet circulation patterns. What goes on in the winter, with the effects of ice and storms, scientists don’t know. Because the research reserve doesn’t keep boats in the water in the winter and ends the drift study in October, a late fall-winter study hasn’t been done.

Mark Johnson, professor of physical oceanography at the UAF Institute of Marine Science, will analyze the two years of data and write up a report in the near future. Johnson has already done a similar report on Cook Inlet circulation patterns. As much as scientists learn, the new information won’t answer every question.

“Like any study we’ll probably end up generating more questions than answers, but that’s great,” Baird said.

Michael Armstrong can be reached at michael.armstrong@homernews.com.

Kachemak Bay Circulation Patterns

What: A study with satellite-tracked drifters to determine current circulation patterns in Kachemak Bay

Who: The Kachemak Bay Research Reserve and the University of Alaska Fairbanks, funded by the Coastal Impact Assistance Program

When: Spring and summer of 2012 and 2013

How: Scientists deploy satellite-tracked drift buoys with drogues to analyze deep- and shallow-water currents

Learn more:

Monday, Noon-1 p.m.,

brown-bag lunch presentation

6-7:30 p.m., discussion forum

Alaska Islands and Ocean Visitor Center

Tuesday, 6:30-8 p.m. presentation and discussion

Seldovia Library