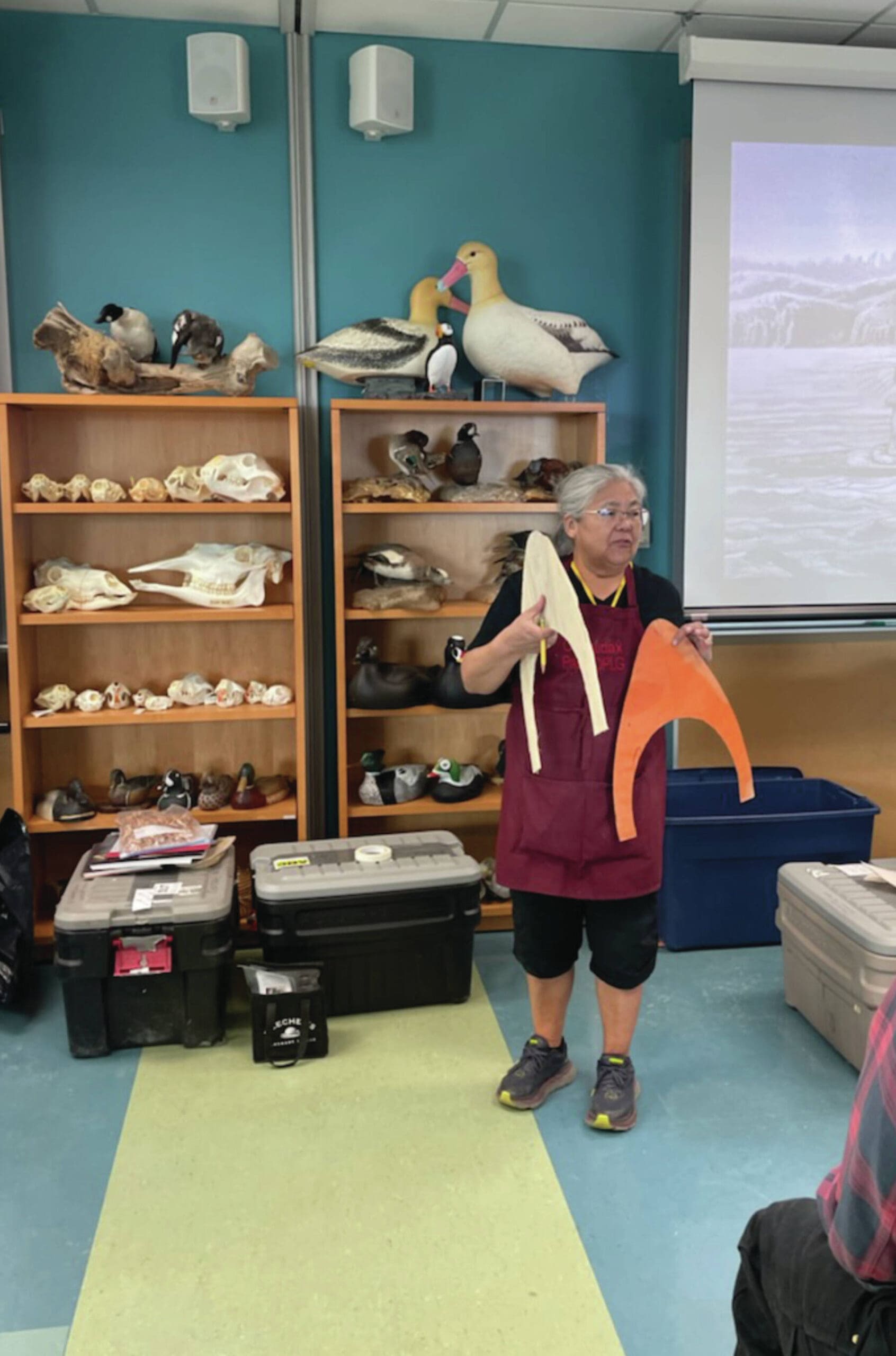

Unangax bentwood hat maker Patty Lekanoff-Gregory from Unalaska visited Homer this week to provide an instruction course in creating traditional Aleut bentwood hats.

Her visit started off with a community lecture on the art and history of the hats at the Alaska Islands and Ocean Visitor Center on Saturday. In his introduction, Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge Manager Steve Delhanty called Lekanoff-Gregory an “Alaskan treasure.”

“The refuge has been the homeland for people for thousands of years of Aleut people. They have rich and wonderful culture that endures today. It’s not just a history lesson, it’s present tense. People live and thrive there and Patty is going to introduce some of the treasure of the hats, an item of both beauty and function.”

Lekanoff-Gregory started learning the art of hat making from Andrew Gronholdt of Sand Point in the early 1990s. She took several courses with him through the University of Alaska and then engaged in personal mentoring. Gronholdt was a boat builder earlier in his life, already knew how to work with wood, and was inspired to start reconstructing the hats in the early 1980s after exploring images primarily from museum archives.

According to Lekanoff-Gregory, there were few other people engaged in hat making at that time and he is the person who deserves credit for preserving the almost lost art.

Lekanoff-Gregory explained the lack of fresh wood on the Aleutian Islands and how hats were traditionally made with driftwood. Now, the wood she uses for her classes is typically milled lumber. She told the audience her parents were also both from villages in the Aleutians. Her father was from Makushin and her mother from Kashega. They were both living in Unalaska and were evacuated to a relocation camp to live in Sitka for several years.

Discussing different types of wood and their qualities, she explained that some of the original hats were made of red and yellow cedar but in Gronholdt’s study he also found the use of cottonwood to be prevalent.

“Well, that’s convenient! I can use the cottonwood to make art and my husband can burn it to make smoked salmon to feed me,” she said.

The first step in making the hats is to carve until the wood is very thin.

“You’ll think you’re finished chiseling and I’ll tell you to sand some more,” she said. “It takes a lot of sand and oil. Many of the designs we’ll use in our class are an original Andrew Gronholdt design.

“You’ll see a little AG on the pattern and know it came from him.”

After appropriately sanded, hats are then boiled to soften and mold the wood.

Lekanoff-Gregory also uses a “jig form” originally created by Gronholdt. A “jig form” is a mold the hat sits on to properly shape as it dries. Dave Gregory, Patty’s husband, has made efforts to recreate the jig forms as well.

The inside of the hat is traditionally stained red and the art on the exterior of the hat is very elaborate.

“The hunters wouldn’t get in the boats without their hat. They thought it was very important because the art on the hat would attract the sea mammal. The whale, the sea otter or the seal would give himself to the man with the most elaborate hat,” she said.

She explained that the designs likely had specific meaning but it wasn’t a written language system so there’s not certainty in contemporary meaning analysis. “One of the symbols that was always important was to have an image of a man sitting on the front of the visor. I still try to replicate the art that our ancestors used to honor them.”

Another feature typically included on the hat design was real sea lion whiskers, she said. The whiskers were covered in a gut intestine regalia to make them longer and help with preservation by providing water proofing. Historically, the whiskers might have been 2 feet long but hunting regulations are more restrictive now and to replicate the decorative component artists often use fishing line.

Hats were traditionally made in variable different sizes. The youth were given shorter visors and the sizes progressed as they aged. The chief’s hat was also constructed more elaborately. She references the book “Aleut Art: Unangam Aguqaadangin” by Lydia Black who cites that the hunter was typically buried with his hat, a personal item of pride.

Now that wood is easier to obtain through purchase, Lekanoff-Gregory displays many additional sizes in her collection, including miniature models used for things like Christmas tree decorations.

Lekanoff-Gregory teaches the art of bentwood hats across the state of Alaska and often contributes to Aleut Urban Culture Camp, which is typically held in the third week of July at the Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association headquarters in Anchorage, according to the association website.

The website also states that “the free one-of-a-kind camp” is open to community members residing in the Aleutian Pribilof Islands Region, the Greater Anchorage area, the continental U.S. and internationally.

However, participants are primarily of Unangax̂ or Aleut descent. If too many applications are received, the camp gives priority to tribal members who are enrolled in one of the 13 tribes served by APIA, the site said.

More information can be found at https://www.apiai.org/.

Camp activities also include learning about traditional foods, glass ball beading, dance, basket weaving and drums. Additional camp sites are located in King Cove, Sand Point, Unalaska and Atka.

Lekanoff-Gregory is often commissioned to make hats for commemorative events such as university graduations or wedding ceremonies. Or, she noted that a community might commission a hat to display in a city office or museum.

Lekanoff-Gregory also serves as an instructor for the Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association, Qawalangin Tribe of Unalaska, and Qagan Tayagungin Tribe of Sand Point. She works also works as an administrator for the Aleutian Pribilof Islands Restitution Trust, according to the Aleut Corporation website.

The workshop offered to the community of Homer is a weeklong course that started on Sunday and will conclude on Saturday. The course is provided at the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge lab and is coordinated by visitor center manager Lora Haller.

The lab was open for several work and instruction sessions each day for participants to complete the hats. Work on the hats involved several hours of sanding, carving and painting. The cottonwood for the hats was supplied by Ben Gibson with Homer’s Small Potatoes Lumber.