AUTHOR’S NOTE: In the first two parts of this story, a woman named Miriam “The Goat Woman” Mathers died on the beach at Kenai in the spring of 1950, and area residents speculated about her past as her meager estate was settled. A registered nurse in Iowa as a young woman, Mathers married at age 34, moved back to her home state of Nebraska and began a family marked by tragedy.

Living with Loss

In late June 1950, about a month after the death of Miriam Mathers in Kenai, an obituary for her appeared in a newspaper in Waterloo, Nebraska, home of one of Miriam’s younger sisters, Ruby Teel. Some of the information contained therein was well known, as Mathers’ quest to homestead in Alaska had been covered by the Associated Press and United Press International during the early 1940s.

But a few notes in the obituary were of a more personal nature, of the kind shared in frequent correspondence between sisters. For instance: “Mrs. Mathers … was the mother of four children, three of whom died in early childhood.”

On Feb. 13, 1919 — 14 months into Miriam Davidson’s marriage to Thomas J. Mathers — a one-sentence notice appeared in the society column of the Tryon (Nebraska) Graphic: “Mr. and Mrs. T. J. Mathers and baby, of Heartwell, Nebr., are visiting their relatives Mr. and Mrs. D. A. Mathers, Mr. and Mrs. Chas. Lilley and Mr. and Mrs. Raymond Newman this week.”

There is no indication of the baby’s age or the gender, but in December 1919 the family welcomed the birth of a son, Charles DeVere Mathers. By the time the U.S. Census was enumerated the following year, however, Miriam and Thomas were listed as the parents of only 1-year-old Charles.

In late February 1923, a local Nebraska newspaper announced the birth of a daughter, Mary Ellen Mathers. Only seven months later, the Mathers family was living in Careyhurst, Wyoming, when a notice appeared in the Casper Star-Tribune announcing that Mary Ellen had died.

At some point, probably between 1919 and 1923, Miriam and Thomas Mathers produced a fourth child who also died as an infant. Whether the trio of deaths or something else entirely drove them apart, the wheels soon fell off the Mathers marriage.

By the time of the U.S. Census in 1930, Miriam was living with her 11-year-old son, Charles, near Big Piney, Wyoming. Miriam was listed as a rancher and head of the family. Thomas was not listed.

According to a Mathers family website, it is likely that Miriam and Thomas divorced in about 1927, although no record of that divorce has yet been found. After their split, Miriam began referring to herself as a widow, even though Thomas was still alive and would go on to outlive her by two months.

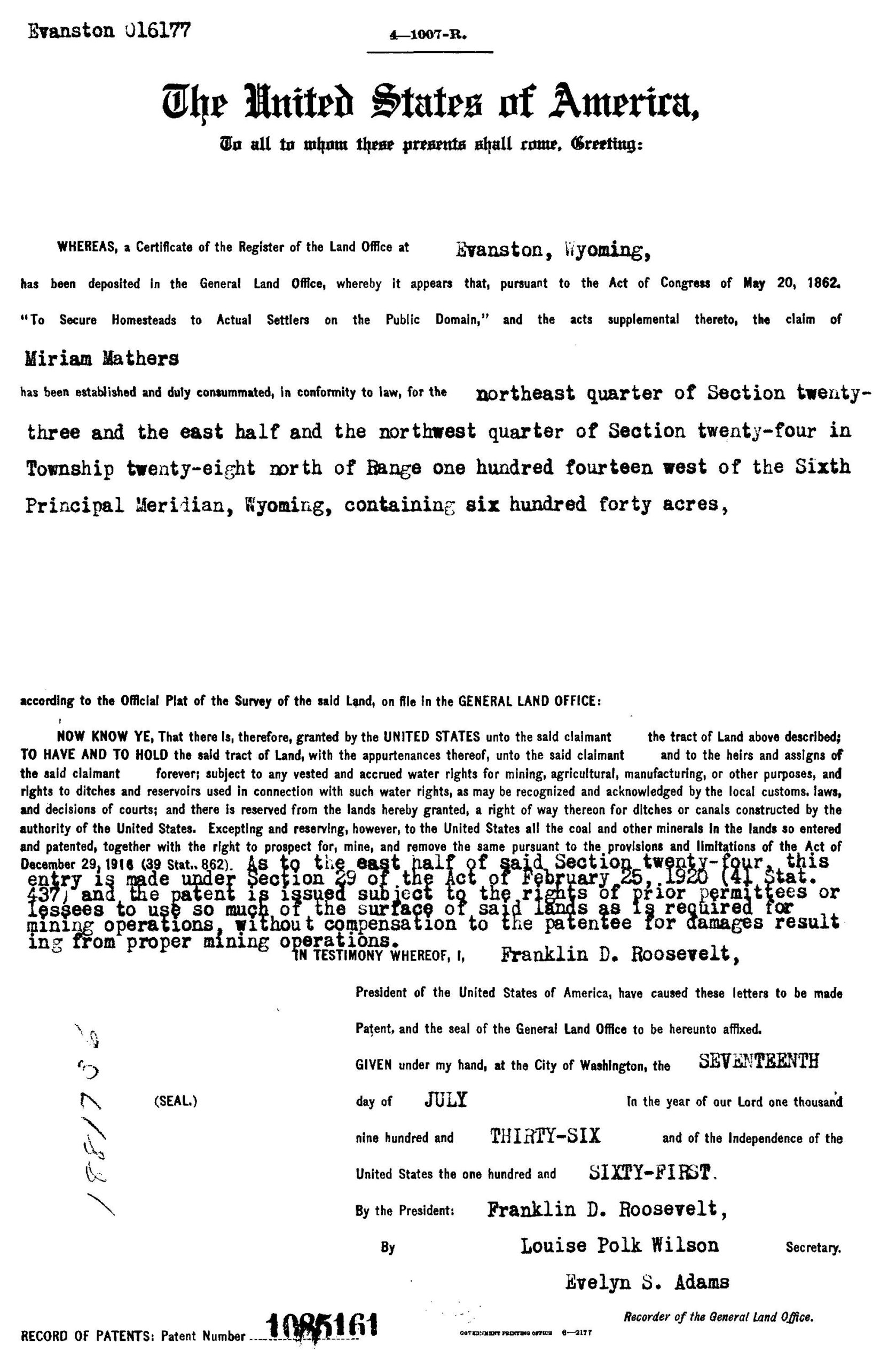

On July 17, 1933, Miriam Mathers applied for a 640-acre stock-raising homestead near Big Piney. She received patent to the land three years later, but by the time of the 1940 U.S. Census, she had left Wyoming and her homestead behind. She and her 20-year-old son were living in Stevens County in eastern Washington.

Her quest for Alaska had begun, but another date with tragedy lay just around the corner.

By October 1940, Miriam and Charles were in Yakima County in southcentral Washington, and by the summer of 1941 they had reached Seattle. Charles was a resident of the New York Hotel and was working as an engineer.

On July 15, Miriam learned that Charles had suffered a ruptured appendix and had died that morning. Funeral costs were covered by the King County welfare department.

Rather than attempt a trip to Alaska in the aftermath of her son’s death, Miriam opted to wait. She moved back to Yakima County, leased 10 acres of Native American land near Wapato, and settled into a life of farming.

But by mid-March 1943, according to newspaper reports, she was “tired of Indian rules and regulations” and was ready to leave. One paper stated that Mathers believed that in Alaska she could “get land of her own and be her own boss.”

Trek, Interrupted

Mathers departed Wapato planning to travel overland all the way to Alaska. She had read about the construction of the Alcan Highway, and she hoped that authorities would allow her to travel the highway route — or some alternate path north — no matter how rough it might be.

She had built her own iron-wheeled, covered wagon and packed it with provisions and household goods, including a narrow bed covered with a feather mattress. She had hitched two bay horses (Bill and Mollie) to the front of the wagon, tethered three milking goats to the tailgate, placed Tubby, her 12-year-old cat, on the seat beside her, and set off.

The Bellingham (Washington) Herald picked up her story quickly. An April 14 article described Mathers as having “plenty of determination in her clear blue eyes and in the set of her sun- and wind-weathered jaw. A wide-brimmed straw hat shaded her face and nearly covered her gray, bobbed hair.”

When someone asked whether she’d encountered any problems crossing Snoqualmie Pass into western Washington, she replied, “No, not a bit. Just new arrivals.” Mollie, her mare, had given birth to a colt, and a few days later a nanny named Pat had produced three kids. The other nanny, named Isabelle and also pregnant, was expected to deliver soon. The increase in young’uns was slowing her down.

The next day, Isabelle gave birth to triplets. Mathers gave away some of the baby goats and kept her menagerie on the move. By April 19, she still had all three horses, the cat and six goats.

Mathers told a reporter that in Alaska she planned to live near a cannery so she could work there seasonally, and then farm and trap on her own place the rest of the year.

The reporter asked whether she was afraid of all that lay ahead of her. “Afraid of what?” Mathers replied. “Life is hard, of course, but it won’t be any harder in Alaska than it’s been down here.” She turned her wagon toward Sumas, one of the last stops before the international border.

By mid-May, she was forced to change plans. Both U.S. and Canadian customs officials had refused her passage because she lacked the proper paperwork. Canadian officials added that, even with the necessary papers, they would require a 30-day quarantine period to ensure the health of her livestock.

Mathers expressed confidence that she would free herself from this snarl of red tape. She traveled south a short distance and set up a camp to wait. But the red tape persisted and she surrendered.

She returned to Wapato, where she again leased land and built a cabin of her own. A year later, she moved to Conrad, Montana, to work, and to the orchards of north-central Washington to earn money. By the fall of 1945, she could afford to hire a truck to haul her wagon, her animals and herself to Seattle.

On Oct. 3, Mathers — along with her wagon, four goats and three horses — were aboard the S.S. Denali in the Port of Seattle and drawing more media attention. According to an AP story the day before, “Alaska Steamship Co. officials said the crew had fallen in love with the smiling, ruddy faced pioneer and ‘is waiting on her hand and foot.’”

A photo of Mathers and her goats appeared in the Spokane Chronicle, and she was asked about her plans once she reached Seward. “I’ll hitch up my team and find me a home,” she said. “I think some of the restlessness will be out of me by then.”