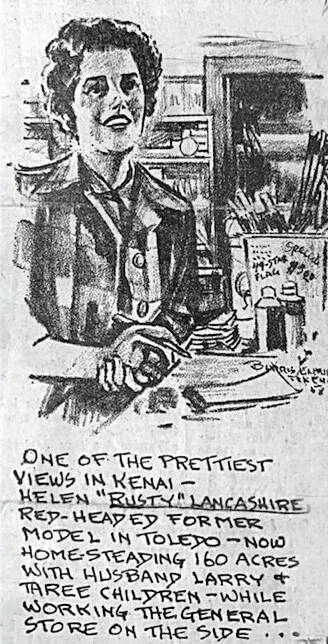

AUTHOR’S NOTE: By the first of August 1948, Larry and Rusty Lancashire and their three daughters (Martha, Lori and Abby) were well under way in building a new and independent life on their homestead on Pickle Hill. Living in a wall tent not far from the new Kenai Spur Road, they were erecting a sawmill and a cabin farther back in the woods. They had hand-dug a water well and were awaiting a pump.

By September 1948, Larry and Rusty Lancashire’s first real Alaskan home—a 15-by-26-foot log cabin, one story plus a basement—was taking shape. The walls and the ridgepole were up. They had used old carpet strips for chinking; when those ran out, they used native moss.

Basement walls were planned next, followed by a floor and doors, all in time for winter, they hoped. Windows ordered in early June would arrive by next spring, possibly sooner if a shipping strike ended.

Because of the strike, they were also running low on basic foodstuffs, so area neighbors chipped in to keep them fed. Brothers Alex and Marcus Bodnar contributed potatoes. Sergei Pete gave them a moose roast. Jettie Petersen, wife of the local marshal, delivered some lettuce and turnips. And so it went as autumn arrived and passed, and the cold began to settle in.

When their new pump arrived, they struggled to set it deep enough to be effective; consequently, they were able to generate only about five gallons of fresh water per hour. At some point, they sensed, they would have to hire a professional well driller to come in and bore down to a more productive source.

By Oct. 1, they had moved out of their tent and into their cabin. Rusty was delighted: Living in the tent had been “terrible,” she said. “Abbie (who was nearing her first birthday) couldn’t get down on the floor. It meant the poor little gal got confined to her crib day in and out…. Imagine not sweeping your floor for three and a half months.

“The floor was ground so fine (that) when you crawled into your beds at night a fine cloud of dust would circle you,” she continued. “It’s over and tucked into our mental files as an experience not to experience again … if it can be avoided.”

As winter loomed, the Lancashires felt their first Alaska earthquake and they worked to fill their larder. Although Larry was not a resident and didn’t yet qualify for a hunting license, he took a borrowed boat out on the Kenai River to see what he could get. He returned with one teal and a sow and cub black bear.

In November, after Harry S. Truman was elected president and the deeper freezes had set in, Larry and neighbor Dick Wilson harvested an illegal moose, carefully sharing it with select neighbors while attempting to keep their crime a secret.

“All the next day they worked cutting it up—we didn’t waste a thing,” wrote Rusty in a letter to family Outside. “We had to be careful who we gave it to, also.”

“(Marvin) Smith and (Ira) Little came up after dark with their packs and walked four miles through snow and down the section line so no one would see them,” she added. “Mal and Grace Cole came out in their dump truck and hid some to take home. I canned 21 quarts (and) ground mooseburger till my arm about fell off.”

In the same letter, Rusty also mentioned a crucial part of the expanding Lancashire infrastructure: the family outhouse. She called it “a small hotel, that place that is to give one great relief and comfort,” except for the initial connection of seat to seat, which she referred to as “the feeling of the electric chair—oh! the shock of sitting on ice!”

In January, their well froze up, forcing them to return to their earlier treks to Soldotna Creek for fresh water. Larry Lawton, manager of the Civil Aeronautics Administration office in Kenai, offered Larry the use of his well driller in the spring, if the Lancashires promised to keep its use a secret.

The cabin windows finally arrived during the next month. They installed them on Feb. 27.

Earlier in the winter, Rusty reported, the camera that they had been using to document their homesteading progress was stolen. “Dick Wilson borrowed it,” she wrote, “and someone stole it out of his truck. That guy—he borrows everything from Larry, then complains because we have poor equipment.”

Progress

Over the next few years, the Lancashire estate continued to grow. By February 1955, when the family starred in a feature article in Better Homes & Gardens magazine, they had expanded their cabin to include a bedroom, a kitchen and a bathroom (without a toilet at that point).

They considered their home a “working farm,” which included a barn with a hayloft, a smokehouse, a greenhouse, a chicken house and a storage shed—all constructed largely by Larry with timber he had cut at his own sawmill.

A gasoline-powered generator ran the pump for their well, so their home had running water. They had cleared, with outside help, about 40 acres of land, six of which were planted in the Lancashires’ cash crop—potatoes (branded “Peninsula Pride”), which they had been selling on contract to the military base at Wildwood, north of Kenai, for the past year.

Around the property, visitors could see well-worn equipment and vehicles, 30 chickens, a Gurnsey cow named Forget-me-not and two calves, a black dog named Mickey, and a tabby cat named Snow-white. A few years earlier, they had also had two horses (Prince and Belle) and a cat named Axel; they’d sold the horses to a Homer old-timer, and Larry had accidentally killed the cat by running over it with his tractor.

The Lancashire daughters were expected to provide labor on the homestead, particularly in the grading of potatoes. For their work, Larry paid them five dollars apiece per week.

Middle daughter Lori recalled wanting to use her money to buy a cute $40 dress she had seen in Seventeen magazine. She said she did not request her allowance for eight weeks and then went to her father to collect the full $40 he owed her in one lump sum.

“I bought the dress and wore it on the homestead,” she said. “Definitely not homestead style.”

Lori also recalled the time that Forget-me-not was bred and gave birth to a little bull they named Red. “As Red matured,” she said, “he got a little aggressive, so Dad slaughtered him. Martha, Abby and I would not eat Red. So Dad ate prime beef the whole winter, and we ate moose.”

By the end of the 1950s, Larry had built a new frame house, with a fireplace, on the property and had moved his family out of the old log cabin.

The Lancashires had settled in. They were involved in community affairs and had a wide circle of friends and acquaintances. The girls were attending school in Kenai. They had a reliable cash flow, and they knew that their own labors supplied most of their food.

A few years earlier, Rusty herself had mused, “Underneath, I have a liking for the outdoors. I don’t where I got it—never realized it until I thought about leaving here. I couldn’t stand living in the states again—you can’t feel as free as you do here. I haven’t heard a train or a telephone for almost a year. They just clutter up one’s life.”

Of his own feelings about homesteading versus the life he might have had if he had never moved north, Larry told the author of the Better Homes & Garden article, “The government spent a lot of money training me to me to be a pilot, but I almost never think about jockeying an airplane up here. I spent some money on myself on an education, and I guess I don’t use much of that (either). But you can’t spend your whole life just being proud of making a little more money than somebody else. Up here, there’s something—call it satisfaction.”

Times were good for the Lancashire clan. They wouldn’t always have smooth sailing, but, like other homesteaders figuring things out as they went along on the central peninsula, they wouldn’t have had it any other way.