The Kachemak Bay Writers’ Conference welcomed author Robin Wall Kimmerer as this year’s keynote speaker, to the enthusiasm of conference attendees and community members alike.

A “mother, scientist, decorated professor, and enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation,” according to the writers’ conference website, Kimmerer is the author of “Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants” and “Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses.”

Kimmerer’s work has also appeared in Orion, Whole Terrain, and numerous scientific journals, focusing on subjects including plant ecology, bryophyte ecology, traditional knowledge and restoration ecology, her bio states.

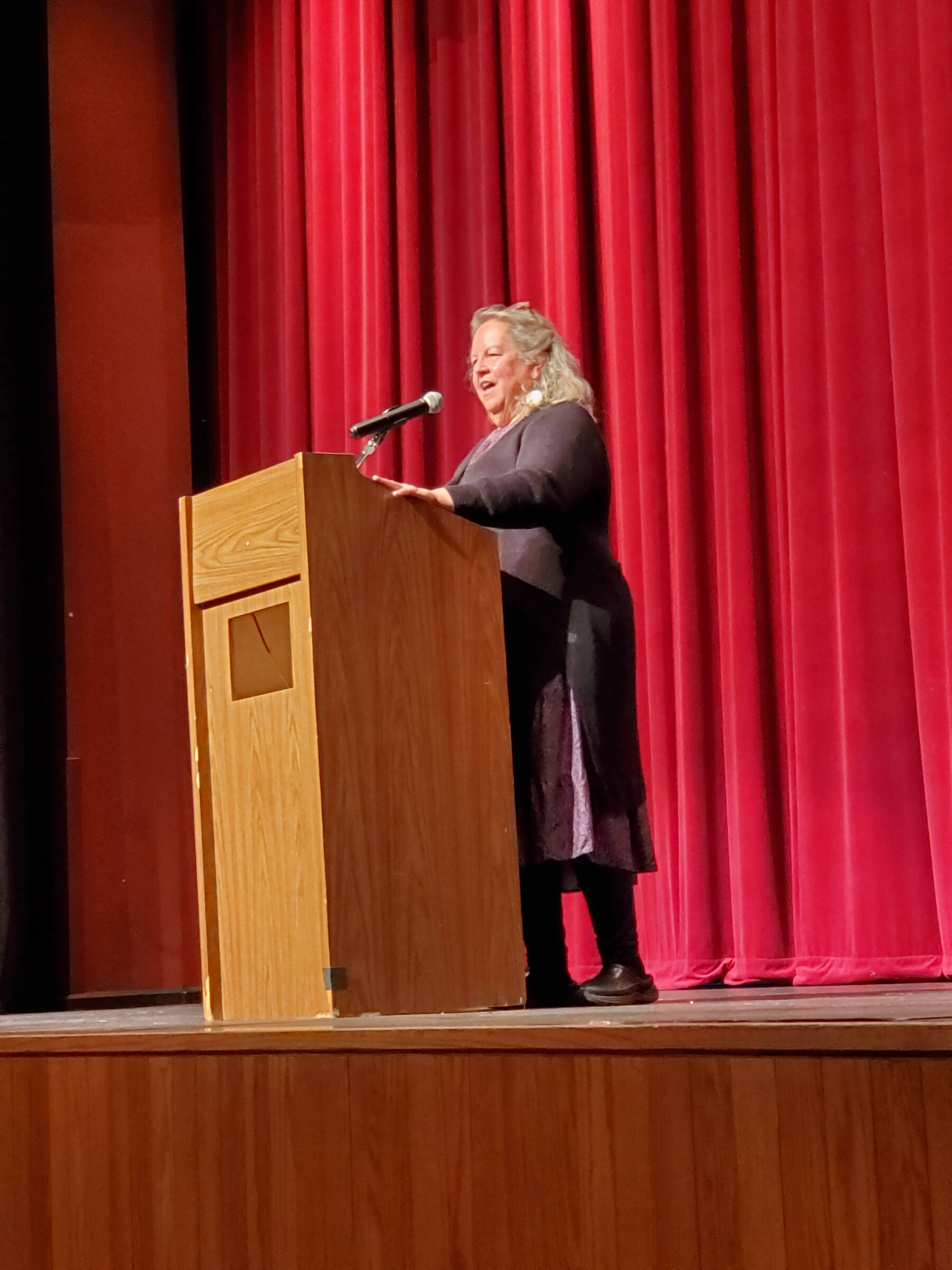

Kimmerer gave her first keynote presentation on Saturday morning at Kachemak Bay Campus, after being introduced by University of Alaska Anchorage Provost Denise Runge and greeting conference attendees in her Native language according to Potawatomi traditional protocol.

“I’m really excited to learn from you and learn from this place,” Kimmerer said as she addressed the audience gathered in KBC’s Pioneer Hall. “I’m really grateful for everything that we have been given that brings us here together.”

In her presentation, Kimmerer recognized that within the group of attendees were “many, many crossers of boundaries” and used that as a jumping-off point to ground her talk in the “pluralism of crossing boundaries” and what can be learned when the world is viewed through more than a singular lens.

“I want to acknowledge that [like] crossing cultural boundaries, from Anishnaabe ways of knowing to the ways of Western science, or crossing geographical boundaries, for me I’m being a scientist in a community of writers,” she said. “I can’t wait to learn from you. Let’s celebrate and erase those boundaries so we can move together and grow together.”

Kimmerer illustrated by sharing where she currently lives in the territories of the Onondaga nation compared to where her Potawatomi people traditionally come from.

“Our two nations speak different languages, we have different cultural histories, and yet we share this abundant generous Maple Nation that we live in, in the Great Lakes,” she said.

Long before settlers came to America, Kimmerer said, the Onondaga and Potawatomi nations had an agreement with each other about how they would live on the land. She showed the audience a photograph of a treaty belt made of wampum beads crafted from quahog shells, which tells the story of nagaan ge bezhig emkwan, or “the dish with one spoon.”

“This story that goes with this, all contained in this visual metaphor, is that we agree that while we are different nations, we are all supplied by the dish that Mother Earth fills for us,” Kimmerer explained. “And we celebrate everything that is put into that dish for us. But as two nations, we agree that our primary responsibility is gratitude for what is in that dish, and to keep that dish clean, and to keep it full.

“This story, this Indigenous literature written in the wampum, is a story about justice and sharing, and that there’s not a big spoon for some people and a little spoon for others. Two nations, one spoon,” she said.

Kimmerer also spoke on the grammar of animacy, the subject of one of the chapters in “Braiding Sweetgrass,” which is “a way of thinking about life and the world.” One of the main points that she shared in her talk was with regard to linguistic imperialism and linguistic restoration. Through a Western lens, land is “nearly synonymous” with natural resources and property, Kimmerer said. However, through the Indigenous lens, land is identity.

“We are inseparable from the land; the land is who we are as people,” she said. “Land certainly as our sustainer, land not only as our home but home to our more-than-human relatives as well, land as our ancestral connection, our source of knowledge, our teacher. … Land never as the place to which we claim property rights, but the place for which we accept moral responsibility for all creation.”

Kimmerer told the audience that “words matter,” that language — the words and grammar — that people choose have “real consequences on the land.” She discussed the ways in which language can undo the consequences of linguistic imperialism and work at healing the Earth.

“Grammar is the map of relationships among ideas and words,” Kimmerer said.

With the grammar of animacy, Indigenous languages like the Potawatomi language uses the same grammar for nonhuman beings as it uses for human family members, overriding what Kimmerer called “human exceptionalism.” Kimmerer advocated for a shift in the Western worldview from referring to nonhuman beings as “it” to recognizing the personhood of all beings.

“What if every time we spoke of the living world, we breathed out into the world relationship, respect, reciprocity, mutuality?” Kimmerer said. “Is this a way that language and writers can topple the pyramid of human exceptionalism and remember who we are in relationship to everyone else?”

Kimmerer expanded on the idea of “remembering” during her public keynote reading at the Mariner Theatre Saturday evening, talking not only about remembering as an act of memory but also “re-membering” as an act of reclamation and conservation. She read an essay titled “Tallgrass” that was commissioned by online journal The Clearing, published by Little Toller Books, to mark the Remembrance Day of Lost Species.

“Tallgrass” is centered on a trip Kimmerer took to Emporia, Kansas to see the prairie — or what remains of the old Tallgrass Prairie ecoregion before it was destroyed by development and diminished to the point of endangerment, Kimmerer explained as she read to the gathered audience.

“As we stand together for Remembrance Day For Lost Species, I want to raise a song for all of those beings knit together by the roots of prairie sod,” Kimmerer wrote in “Tallgrass.”

“I refuse to write a eulogy for one alone, because the very notion of separability is at the root of the crisis we have created. … Our work is not to eulogise them, but to fuel the fires of renewal.”

Kimmerer also spoke about the role of the nature writer today, referring to how nature writing was once directed to inform and share knowledge with people about the nature of the world.

Kimmerer uses her Potawatomi name, which in English means “Light Shining Through Sky Woman,” to consider her role as a nature writer as being to “illuminate, to cast light on places on the earth so that we can see more fully the beauty that is there, the teachings that are there.”

“I think today, in the age of information overload, when information is at our fingertips, we’re beyond needing more information,” she said. “I think it is wisdom that we need.

“I think [the role of the nature writer today] is to change the story. To wake people up to say ‘why are we not acting?’ Because we need a different story about who it is that we can be as people in the world — not just takers from the earth, but givers to the earth. To remember our roles as human peoples … To remember ourselves as members of the more-than-human world.”

Kimmerer told the audience that when she was writing “Braiding Sweetgrass,” she had written in her journals that she wanted the book to be “medicine for a broken relationship with the world.”

In the Potawatomi language, she said, the word for medicine is the same as the word for plants and means “the strength of the earth.”

“What is it that heals? The strength of the earth. What is the medicine that we need? The strength of the earth,” Kimmerer said. “So I think that by illuminating the strength of the earth, that’s where stories can be healing, where stories can be medicine. So in this time of crisis and opportunity, I think the role of writers is to be healers as well.”

Kimmerer received a standing ovation from the audience at the conclusion of her reading.

For more information on Robin Wall Kimmerer, visit https://www.robinwallkimmerer.com/. Her essay “Tallgrass” can be found at https://www.littletoller.co.uk/the-clearing/tallgrass-by-robin-wall-kimmerer/.