AUTHOR’S NOTE: Ethen Cunningham came to the Kenai Peninsula in about 1940. He homesteaded along the lower Kenai River and began commercial fishing north of Kenai. In 1945 in Wisconsin, he married Martha Sievers and moved her to his homestead. A year later, he met William Franke, who would become his neighbor and shoot Cunningham dead in January 1948.

The Motive

In his memoir, “Alaska Odyssey,” former Kenai resident Hal Thornton wrote that it was “assumed” that William “Bill” Franke had killed Ethen Cunningham on Jan. 19, 1948, because of “jealousy over one of the wives.” Both men were married and lived on adjoining homesteads.

Franke, he said, had gone to Cunningham’s cabin and “called the man to come outside.” After Cunningham emerged, said Thornton, Franke shot him “point-blank.”

Thornton had only a portion of the story correct, however. The same was true for many of Thornton’s neighbors in Kenai.

Conjecture about motive was rampant immediately after the shooting and in the months before Franke’s court date in March. Longtime Soldotna resident Al Hershberger said that when he first moved to Kenai in March 1948, he knew nothing about Franke or Cunningham, but it seemed as though nearly everyone was talking about the murder. And everyone, he said, seemed to have an opinion.

Some speculated that Cunningham had been having an affair with Franke’s wife. Others said they believed that Cunningham’s wife, Martha, was only pretending when she said she didn’t know the reason for the killing. “How could she not know?” they wondered aloud.

Kasilof historian Brent Johnson, in his yet-unpublished memoir, wrote: “Local scuttlebutt offers either a dispute about dogs or one about women., Franke was a trapper and was probably absent with his dog team at times. Alaskan men have been known to be passionate about their dogs and their women, so either motive fits. I find jealousy over Frank[e]’s wife easiest to believe. Had the dispute been about dogs, Martha would likely have known about it.”

Other residents, too, spoke of a disagreement concerning dogs, but the actual motive — if one were to believe the court testimony of the killer himself — would come out, mostly by implication, before a judge.

It is also worth noting at this point that Brent Johnson’s mother, Ruth, who had just moved to Kenai around the time of the murder, once told her son that the Cunninghams were “very” religious. When asked what made her think so, she replied that the Cunninghams used to hike the local trail to church in the village twice a week. A snowy round-trip from the Cunningham home to church was about 6 miles — a distance Ruth believed only someone dedicated to the church would desire to make.

While Ethen Cunningham’s connection to Christianity is difficult to ascertain, Martha’s is clear. She was a devout Lutheran. Even after Ethen’s death, she continued her affiliation with the church and in the 1950s in Anchorage became involved with the Alaska Eteri Fellowship, an organization for Protestant businesswomen. At one point, she served as president of the Anchorage chapter.

Martha was also devoted to her family back in Wisconsin. While Ethen remained in Kenai, she had spent several weeks of the winter just prior to the shooting visiting her mother back in Sheboygan. She returned to Kenai in early December, approximately six weeks before the murder.

Also interesting to acknowledge is another of Ruth Johnson’s contentions — that William Franke’s wife was pregnant at the time he shot Ethen Cunningham. Johnson was correct. In fact, Mrs. Franke gave birth to a child only seven months after the murder.

Speculating residents who were aware of the pregnancy and were hoping for a juicy infidelity to whet their appetites for scandal may have been counting back to the possible conception date.

William’s Path

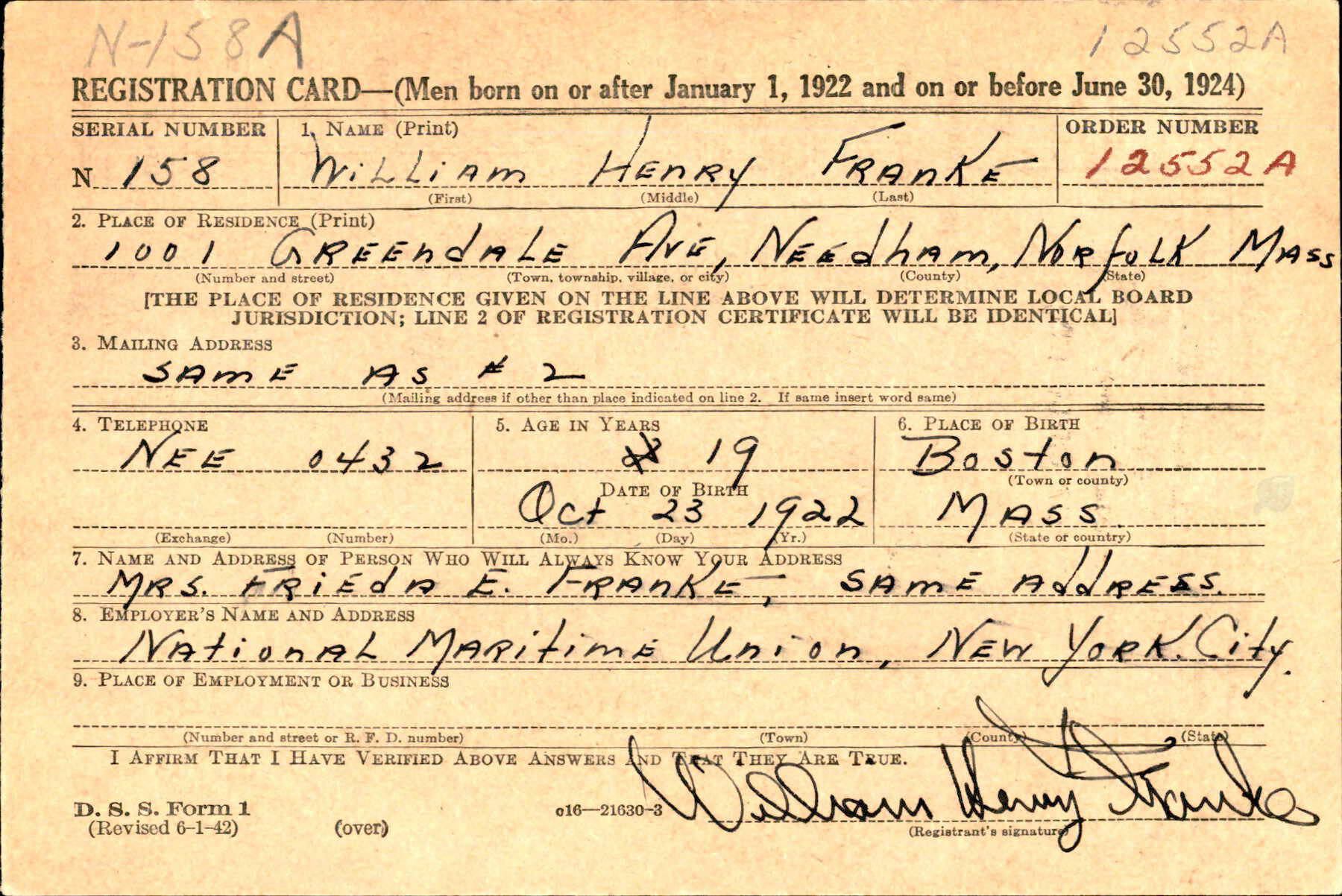

William Henry Franke was born in a Boston suburb on Oct. 23, 1922, to a German immigrant father and a Boston-born mother, William Augustus and Frieda K.E. (Fischer) Franke. By the time he was 19, young William stood 6-foot-1 and weighed 185 pounds, according to his draft-registration card. He was a white man with blue eyes, blond hair and a light complexion. He was frequently described as handsome in news reports.

According to court testimony from his father, William, before the shooting, had never been in trouble of any kind. “He was a very good boy,” the elder Franke told the judge, “(he) associated with the best type of boys in town, and he never had any trouble at all. He done what he could for me and for his mother, and always we were very proud of him.”

Cunningham, by contrast, was physically leaner. He stood 5-foot-11 and weighed about 50 pounds less than Franke. He had brown hair, blue eyes and a light complexion. Because of the early death of his mother, his home had lacked the stability of Franke’s.

In 1940 — the first year in which Cunningham showed up as a resident of Kenai — Franke was just 17, still in high school, and still living at home with his parents. Two years later, he enlisted in the Merchant Marine, a non-military organization (but with ties to the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard) concerned with transporting cargo, and sometimes passengers, from place to place via water routes.

After his initial training, Franke was almost immediately sent out to sea, spending weeks or months at a time away from land. He became an able-bodied seaman and served in this capacity until August 1945, when, as a second mate, he was honorably discharged.

By that time, he had also become a husband.

William Franke married Nancy Hazelton Swift in Tisbury, on Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, on April 11, 1945. Almost certainly, Nancy was pregnant at the time of the ceremony, as their first child, a daughter named Gale Belinda Franke, was born only eight months later.

Nancy had been born Aug. 24, 1923, in Oak Bluffs, on Martha’s Vineyard. Her father, Dean Hazelton Swift, was a civil engineer with family ties back to the American Revolution. Her mother had been born Kathryn Dexter Ripley, and she and Dean and their four children lived comfortably in well-heeled Dukes County.

At some point, William and Nancy Franke made the decision to consider moving to Alaska. The plan called for William, accompanied by Nancy’s brother Dean, to travel north first and check out the possibilities. Nancy and Gale would be sent for later.

William, with Dean Swift, arrived in the Territory of Alaska in July 1946. Their intention, said Swift in court, was “to look over the country and take out a homestead somewhere in the country that suited us.”

“I came up here for the main purpose [of] just wanting to mind my own business and making a living,” added Franke.

By autumn, the two men were on a boat to Kenai. On that boat, they met Ethen Cunningham.

Cunningham encouraged them to check out the riverfront property near his own homestead. He even offered them a place to stay while Franke built a home of his own.

In the Land Office in Anchorage on Sept. 16, 1946, William Franke filed on a 40-acre homestead parcel just west of Cunningham’s land and just north of Windy Wagner’s — all along the outside of a meander near Mile 6 of the Kenai River.

Although the relationship among the men was harmonious at this point, it would eventually sour. In fact, sometime after Swift returned home to Massachusetts, Franke and Cunningham found themselves at loggerheads.

TO BE CONTINUED….