After showing at the Museum of the North in Fairbanks and the Anchorage Museum, “Ron Senungetuk: A Retrospective,” has circled back to the town where Senungetuk spent the last 22 years of his life. The Pratt Museum & Park has added a local twist to the traveling exhibition, including Senungetuk pieces from local collections as well as a stunning display of his early student work.

“That’s what makes it so special down here in Homer,” said artist and jeweler Rika Mouw, one of the curators of the Pratt exhibit and a friend of the Senungetuk family. “It’s school work to some of the last pieces he made in 2015.”

Senungetuk died at age 86 on Jan. 21, 2020, in Homer. After his passing, artists, professors, students and art leaders praised him as one of Alaska’s finest artists and for his advocacy of treating Indigenous art as fine art. Born and raised in the Inupiaq village of Wales, Senungetuk built on his background as a traditional artist to create a distinctive style using Arctic and Alaska themes and imagery, but thoroughly modern.

“Ron Senungetuk embraced ideas of change and connected them with traditional Indigenous concepts in his work,” his daughter, Heidi Senungetuk, wrote in a statement at the exhibit. “Senungetuk often said, ‘In order for traditions to remain traditional, they must always change and adapt to present ways.’”

Da-ka-xeen Mehner, associate professor of Native art and the current director of the Native Art Center that Senungetuk founded at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, called Senungetuk “the grandfather of contemporary Native art in Alaska.”

Senungetuk said he wanted to be known as an artist first and Native second.

“I’d rather be an artist who happened to be Inupiat,” he told the Homer News in 2008.

“What a leader he was,” Mauw said. “He just inspired a new way of thinking.”

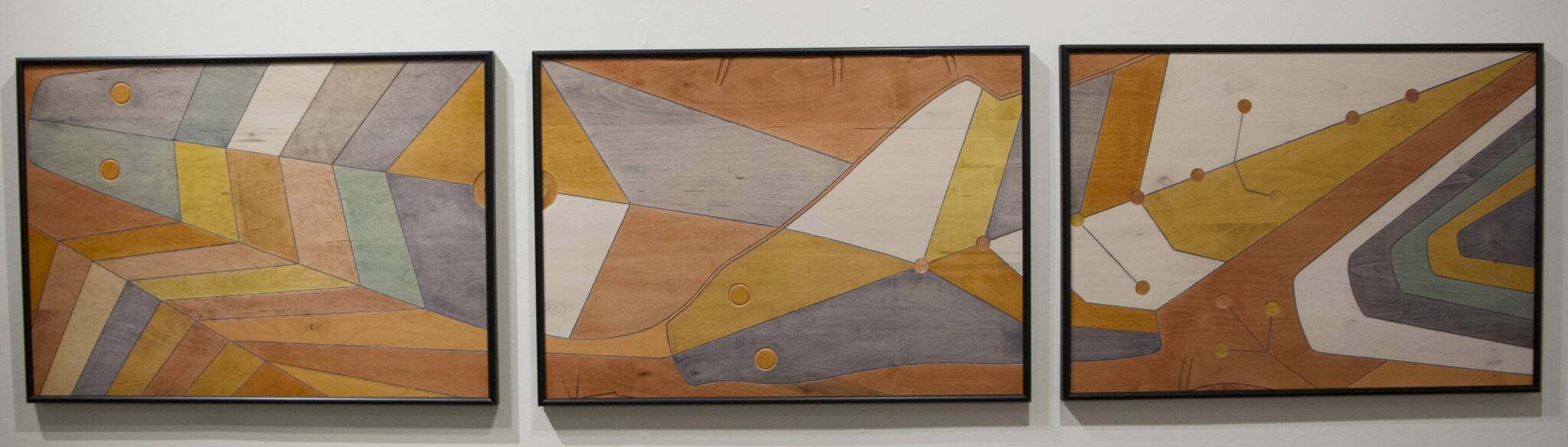

“Ron Senungetuk: A Retrospective” includes works that span the arc of his career. Many of the pieces feature what came to be his trademark media, carved wooden panels lightly tinted in pastel colors. Senungetuk learned woodworking with George Federoff at Mt. Edgecumbe School in Sitka, a boarding school for rural Alaskans. The carved panels came about later in his career after he had established himself as an artist in metal.

Fedoroff encouraged Senungetuk to attend the School for American Crafts at the Rochester Institute of Technology, New York. After his studies were interrupted when he was drafted to serve in the U.S. Army, Senungetuk returned to RIT, graduating in 1960 with a bachelor of fine arts. He had started in wood working but, after his return to RIT, turned to metalsmithing.

His widow, Turid Senungetuk, said that came about because when Ron returned to RIT, the woodworking class had filled.

“He went upstairs and they were hammering around on silver,” she said. “He thought this was an interesting thing. He just fell in love with silver.”

The School for American Crafts had Danish teachers, and they followed the apprenticeship concept of learning, Turid Senungetuk said.

“When you are done, you have to make a piece to show what you have learned in those four years,” she said.

That student project is one of the special works in the Pratt show, a set of silver serving ware complete with salad forks and salt and pepper shakers.

“There’s a lot of work,” Turid said. “It’s all made from a flat piece of silver.”

One piece is a round pot with a lid.

“He was really proud he could take that lid off, turn it 180 degrees, and it would fit,” she said.

It was at her suggestion that the Pratt included the serving set.

“I wanted people to know he actually studied silversmithing,” Turid said. “Here in Homer they mostly know him for his panels.”

Turid and her daughter Heidi showed Mouw Ron Senungetuk’s work at their home, making suggestions about what was too much or not important. Mouw credited the Senungetuks and Bunnell Street Arts Center Artistic Director Asia Freeman as co-curators of the Homer elements of the Pratt show.

Mauw had suggested including another work of Ron Senungetuk’s student art, a work bench he made at RIT. After graduation, he had it shipped to Alaska, and it followed him from Fairbanks to Homer.

“I would have gone crazy,” Mouw said of including more work by him. “…They said, ‘This is an art show, not a memorial.’ They reined me in.”

The show also includes jewelry that Ron Senungetuk made, some of it combining silver with traditional materials like bone and ivory. That’s a common technique of his work. A long wooden bowl that has a Scandinavian style takes on an Inupiaq flair with two pieces of carved ivory like the thwarts of a boat, giving the work the appearance of an umiaq, the traditional skin boat.

A Norwegian-born artist and jewelry maker, Turid Senungetuk met her husband in Oslo, Norway, where they both studied at the Statens Handverks of Kunstindustri Skole. Senungetuk had earned a Fulbright Scholarship to continue his studies after RIT. They fell in love and she followed Ron back to Alaska after she finished her studies. In 1961, Ron Senungetuk was offered a job at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and in 1965 started the Native Art Center.

“He looked around and saw there were no Native young people on campus,” Turid said. “I heard him say, ‘I took it upon myself to help on that.’”

Ron Senungetuk began carving wood panels in the 1970s and 1980s when Alaska adopted a 1% for art law that set aside a percent of a state funded building’s cost for art. One of his first commissions was for the Alaska Native Medical Center in Anchorage. He also did a large mobile of the aurora borealis for a 1% commission in Golovin. The show includes a maquette of the mobile, a scale model Senungetuk made to work out the balance and design of the piece.

The community room at the Pratt shows Senungetuk works from Homer and Kachemak Bay collections, including pieces from the Pratt Museum & Park and the Homer Foundation. Three videos show in the exhibit of Senungetuk talking about his art over the years, including a clip from a 1975 TV show. One video is just of Senungetuk carving.

Turid Senungetuk said it was nice to see her husband’s work gathered together in one place.

“I’ve seen all the pieces being made, but it’s a little different seeing it in the show,” she said “You forget what they look like — like old friends.”

Reach Michael Armstrong at marmstrong@homernews.com.