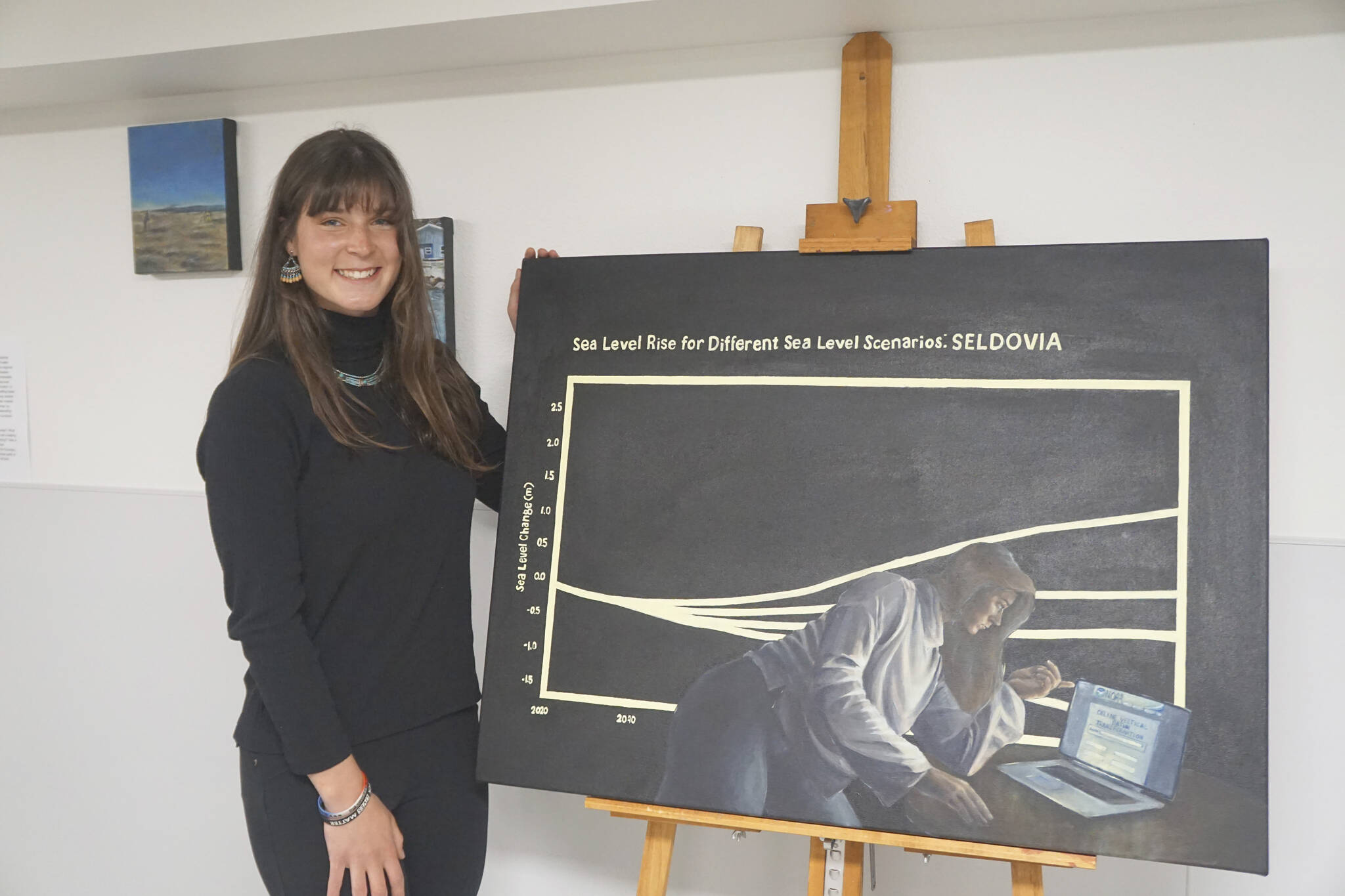

First Friday art goers last week who stumbled upon a show in the basement of the Homer Council on the Arts got a rare and transient glimpse at a creative project that uses art to better understand issues like sea level change and coastal erosion.

The exhibit by Kate Lochridge, a Bowling Green State University, Ohio, fourth-year student, came about after her internship this summer as a National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration Ernest S. Hollings Scholar and Artist in Residence. Now back in Ohio with her paintings, Lochridge’s show went up for just one night. For those who missed the pop-up show, on Aug. 24, from 12:30-1:30 p.m. Alaska time, Lochridge presents a webinar on her internship, with photographs of her paintings, sketches and installations.

Lochridge came to Alaska — her first visit, but she said she knows it won’t be her last — after applying for and winning the two-year Hollings scholarship in her second year of college. Hollings scholars do an internship between their junior and senior years, and go to an online portal to find paid internships. NOAA scientists in turn submit project proposals for interns. A studio art and marine biology co-major, Lochridge found a project for an artist in residence by NOAA Regional Geodetic Advisor Nicole Kinsman of Anchorage. She emailed Kinsman, told her about her background, and got the internship.

Raised in North Campton, Ohio, as a child, Lochridge grew up camping and hiking with her family. Her father came from Tampa, Florida, on the Gulf of Mexico coast, and the family would visit Florida.

“I’ve always loved the ocean ever since I can remember,” she said in a phone interview on Tuesday. ” … That would be our vacation (camping). I really gained an appreciation for nature because of that.”

In Florida she remembered going to an aquarium in the Florida Keys.

“That kind of stuff blew my mind,” she said of learning about marine life. “‘Oh, can we watch ‘The Little Mermaid?’” she remembered telling her parents. “‘Can we watch such-and-such episode of ‘The Magic School Bus?’ Let’s watch those ‘Blue Planet’ documentaries. It kind of grew on me.”

In middle school and high school Lochridge took art classes.

“I always enjoyed doing art. It was a way for me to relax and unwind and explore my creativity and imagination,” she said.

In high school she also studied marine biology, including a class in southern American marine coastal ecosystems that culminated with a field trip to Andros Island, Bahamas. There she learned how small countries on small islands are dependent on marine ecosystems.

At Bowling Green, Lochridge started out as a marine biology major, but took an art class with a professor, Christopher Pickett. Pickett made a point of asking students if they wanted to learn new media not always part of the course.

“He always wanted to make sure people had opportunities that weren’t part of the class,” she said.

When she went to take more art classes, Pickett was surprised to discover she wasn’t an art major, Lochridge said. He encouraged her to be an art major as well and told her, “‘Let’s take a look at your schedule. The way you personify yourself in art class is phenomenal. I think you would benefit from this.”

The NOAA internship took place all in Alaska, starting out and finishing at the Kachemak Bay Estuarine Research Reserve. In between Lochridge stayed at Kasistsna Bay Laboratory, a NOAA and University of Alaska Fairbanks research and educational facility where she worked under the direction of Kasistsna Bay Laboratory Director Kris Holderied.

“Kris is amazing,” Lochridge said. “Not only is she one of the kindest people I’ve met, she goes above and beyond in creating opportunities and partnering with groups.”

In her internship, like a good scientist, Lochridge did a lot of reading. In the field, she matched up what she had read with what she observed.

“For example, being able to go out and find tidal stations and sketch those from life, or looking at houses that were along the coast at different elevations and seeing if they had different adaptations for coastal erosion.”

The pop-up show includes about a dozen paintings, but also Lochridge’s detailed sketch books. In Homer, Lochridge met and got to know other naturalist artists like Kim McNett and Conrad Field. She used Field and other’s research in isostatic rebound — the rising of land after glaciers melt and retreat — in an installation that includes a plastic-pipe grid used to mark off vegetation survey plots.

At first glance, Lochridge’s paintings appear to be classic Alaska landscapes or portraits that evoke an Impressionist style. One painting of a group of tourists standing by the “1899” year marker for where the face of Exit Glacier had been then has that misty glow of a Monet or Renoir — or, it could just be the mist of a summer Seward rain.

A historical painting of the Seldovia boardwalk seems to be a traditional view of the town, but paired with another painting of the same scene flooded on an extreme high tide after the 1964 Great Alaska Earthquake tells a scientific story. Like the Homer Spit, the town sank several feet, and how much didn’t become apparent until the next big tide swamped the boardwalk.

Lochridge’s paintings have a photographic quality, and like good photojournalism, show people doing things: jumping off a Seldovia dock in scuba gear or a person standing on wave-washed rocks to measure tidal ranges. Part scientific illustration, her paintings also make science real — it’s dynamic, not static. That’s a concept catching on more and more in science, she said.

“It’s getting a large pedestal,” Lochridge said.

But aside from meeting scientists, reading about science, and learning about new research, in her residency Lochridge did what artists should do: spending time painting. The lab became her studio where she could indulge in the pure joy of creation.

Looking ahead to studies beyond college, Lochridge said she would like to go to graduate school, but after a few years taking a break from academia. She’d like to do research into sharks and also has a fascination with bioluminescence. On the practical side, she might also go into scientific illustration.

“It opens illustrators up to many, many different fields,” she said. “It’s a great way to learn a little about everything, which has always been fun to do. You never know what you don’t know. It’s really exciting to have your eyes opened up to what’s happening around us.”

People interested in attending Lochridge’s webinar can email her at kate.lochridge@noaa.gov.

Reach Michael Armstrong at marmstrong@homernews.com.