When, in 2020, I considered moving to Alaska, there was no shortage of online forums, Reddit threads and other resources ready to answer everything I could possibly want to know about relocating to the Last Frontier. One of the searches suggested to me by Google was, “Do you get paid to live in Alaska?” Intrigued, I clicked on.

That was the first time I critically engaged with the concept of Alaska’s Permanent Fund. More than three years later, I’ll admit there is still a lot about the fund that I don’t understand. The concept of a state government that doesn’t collect taxes annually sending checks to every eligible resident is, in my opinion, perplexing.

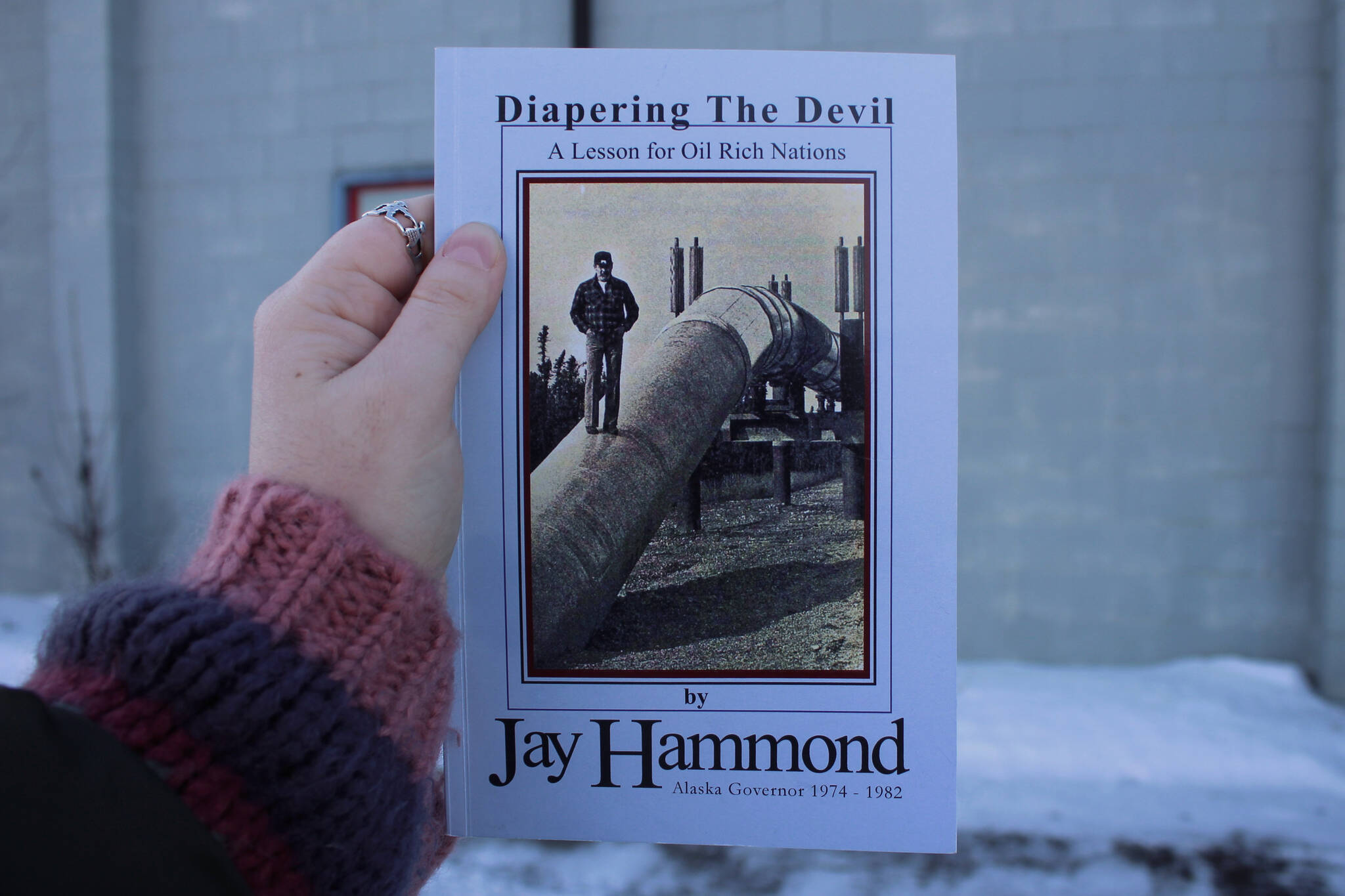

It was in part because of that lingering mystification that I found myself last week reading Jay Hammond’s “Diapering the Devil,” which has sat among the other Alaska texts accumulated by the Peninsula Clarion newsroom since I started working here.

“Diapering the Devil,” albeit 61 pages, is a dense, boot camp-esque explanation of the origins, creation, implementation, pitfalls, implications and function of the Alaska Permanent Fund by the guy who started it. Hammond was the fourth governor of Alaska from 1974 to 1982 and oversaw the fund’s creation in 1976.

The book is an unfinished manuscript that Hammond was working on at the time of his death in 2005. Homer resident Larry Smith, who coordinates the Kachemak Resource Institute, writes in the book’s foreword that he received a copy of the manuscript in 2008 by Hammond’s wife, Bella, and received the family’s permission to publish it in 2010 with some edits.

“It was clear that, at the time of his death, Hammond was in the process of rearranging the chapters and some text within the chapters,” Smith writes. “He did not have the opportunity to eliminate all the duplication, check all the facts, or name all the chapters. The editors did the best they could to make this type of correction, the corrections they believe Hammond would have made.”

The book takes its name from a quote by Venezuelan Diplomat Juan Pablo Perez Alfonso, who founded the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. The quote encompasses Hammond’s basic thesis that governments that put all their eggs in the oil and gas baskets need protections in place to ensure the house of cards doesn’t collapse when the price of oil declines.

“I call petroleum the devil’s excrement,” Alfonso is quoted as saying in the book’s preface. “It brings trouble … Look at the locura — waste, corruption, consumption, our public services falling apart. And debt, debt we shall have for years.”

Something Hammond revisits multiple times throughout the book is Article VIII of the Alaska Constitution, which says that, “The legislature shall provide for the utilization, development, and conservation of all natural resources belonging to the State, including land and waters, for the maximum benefit of its people.”

The duty to manage natural resources for the maximum benefit of residents, Hammond asserts, isn’t limited to oil and gas. He first pitched an investment account that would generate revenue to be paid out to stakeholders while he was manager of the Bristol Bay Borough — the first borough created in Alaska.

He envisioned “Bristol Bay Inc.” as an account into which the taxes of local fishermen would be deposited. At the time, an estimated 97% of the money generated by fishing within the borough’s boundaries was going to fishermen who didn’t live in the borough. By charging all fisherman a tax and depositing the revenue into the investment account, Hammond then planned to annually pay borough residents the value of one share.

The ordinance establishing that program, Hammond writes, was ultimately defeated by borough voters, who he said opposed any form of new taxes. He articulates that his rationale for the permanent fund dividend model is to “pit collective greed against selective greed,” referring to the decision of whether government should spend on behalf of residents, or if residents should decide for themselves.

“I wanted to transform oil wells pumping oil for a finite period into money wells pumping money for infinity,” he writes. “It was apparent that unless we did so, politicians would spend every windfall to satisfy insatiable short-term needs and demands, only to find themselves in a world-of-hurt when oil wealth declined.”

“Diapering the Devil” is a helpful guide on the origin and function of such concepts as the Constitutional Budget Reserve, the fund corpus, the percent of market value, the formulas used to calculate dividend amounts and others.

It is also a concise summary of the philosophy Hammond applies to the permanent fund as a way of fulfilling Alaska’s constitutional obligation to manage natural resources for the maximum benefit of its people. Given what some may say is the Alaska Permanent Fund’s outsized role in contemporary state governance, “Diapering the Devil” remains a relevant and informative text from a legacy figure in Alaska politics.

Reach reporter Ashlyn O’Hara at ashlyn.ohara@peninsulaclarion.com.

Off the Shelf is a bimonthly literature column written by the staff of the Peninsula Clarion.