What makes a good story? Is it one that is so riveting you cannot look away? One that makes you cry? One with a good message? That’s surely a subjective question. Different people like different books for different reasons.

After picking up Velma Wallis’ 1993 “Two Old Women” at the bookstore earlier this month and subsequently finishing it in one sitting, I’ve decided it probably falls into more of a “best all around” category. It was engaging, emotional, left me thinking and was charged with the special energy that comes with a story passed down through generations.

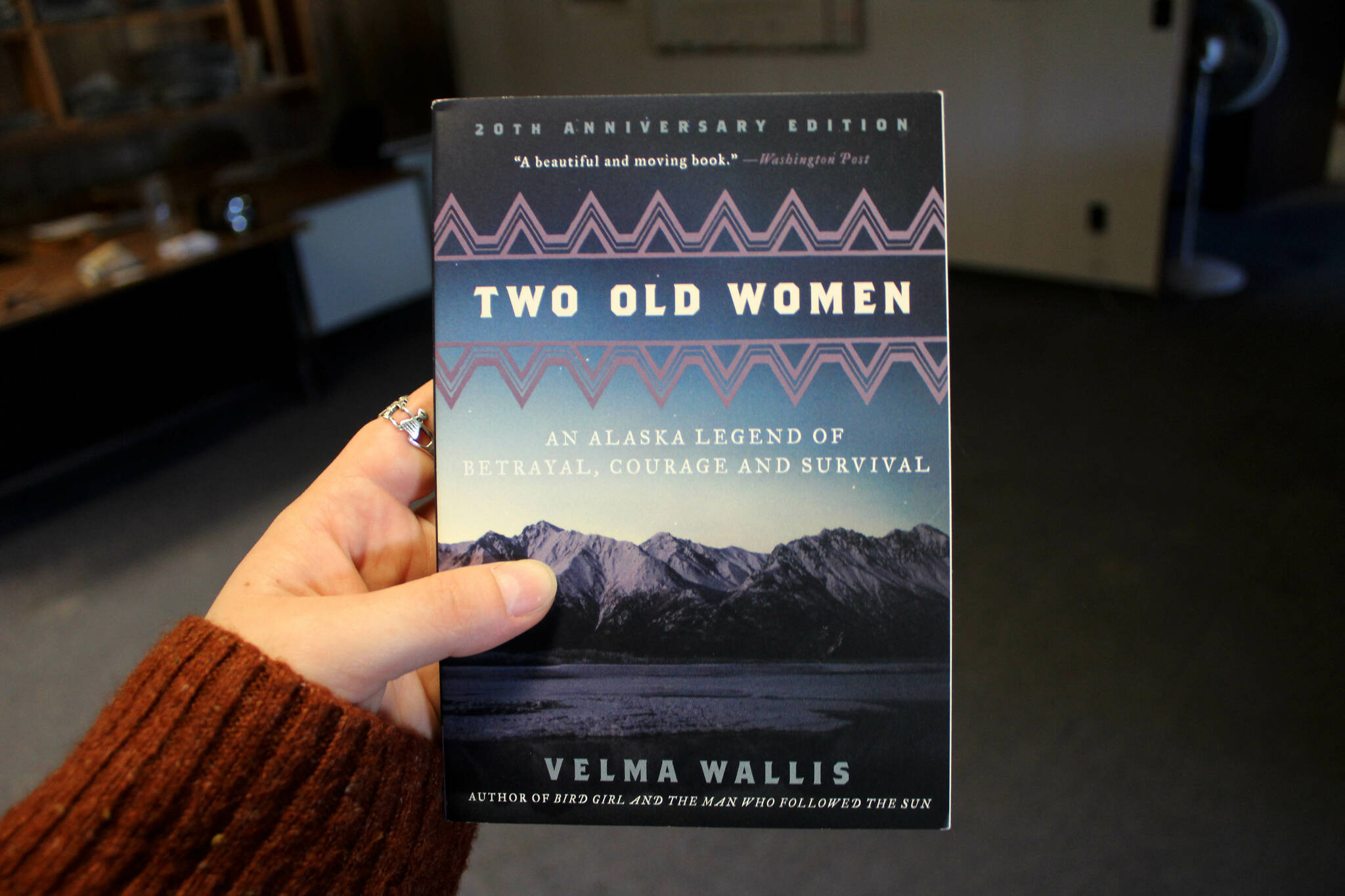

“Two Old Women” is a traditional Athabascan legend as told by Wallis, who was born in Fort Yukon and now lives and writes in Fairbanks. In an introduction to the book — my copy is a 20th anniversary edition — Wallis says she first heard the story from her mother and rushed to write it down shortly after.

As the title suggests, the story is about two old women, Ch’idzigyaak and Sa’, who are abandoned by their people during a harsh winter. Determining that the women, who often complain, are too much trouble to take with them, the chief instructs the people to leave the women behind.

“Like the younger, more able wolves who shun the old leaders of the pack, these people would leave the old behind so that they could move faster without the extra burden,” Wallis writes.

The two women, shocked that they’ve been left behind by their family and friends, resolve that they will not resign themselves to death. Drawing on the wisdom and knowledge that their age has afforded them, they trek to one of their group’s former fish sites. They eventually establish a dwelling and live comfortably, but they still mourn the betrayal of their family and friends.

When the people return, weak and weary from an unproductive voyage, they reconnect with the women, who share with them their store of warm furs and food. The women ask in exchange for their generosity that no one be allowed to visit them. Eventually, though, the women decide that they miss the companionship of others and “The body needs food, but the mind needs people,” Sa’ tells Ch’idzigyaak.

“Two Old Women” left me thinking. On its face, the story’s antagonists appear to clearly be the people who leave the women behind. “What lesson am I meant to take from these plot points,” I found myself asking as I turned the final page. Is the moral of the story one of forgiveness? One of resilience and determination? Both?

More than just a retelling of a legend, “Two Old Women” also contains illustrations by Athabascan artist Jim Grant, a section about the history of the Gwich’in people — one of 11 Athabascan groups in Alaska — and a lengthy dedication to elders who Wallis says have made an impression on her.

I found myself thankful to have read “Two Old Women” after setting it down. Thankful to Wallis for preserving the story and for sharing a story I wouldn’t have heard otherwise.

“Stories are gifts given by an elder to a younger person,” Wallis writes in the book’s introduction. “Two Old Women” certainly feels like a gift from Wallis.

Reach reporter Ashlyn O’Hara at ashlyn.ohara@peninsulaclarion.com.

Off the Shelf is a bimonthly literature column written by the staff of the Peninsula Clarion.