In the genre of war novels, the best books often come from soldier-authors, the men and women who have stared at bullets and mortar rounds and come back to write about war. These writers face a dilemma, though. They write not necessarily for other soldiers, but for civilians. As one Vietnam veteran said when asked if he wanted to participate in last year’s Big Read for Tim O’Brien’s “The Things They Carried,” he’d lived that war and why did he want to read about it again?

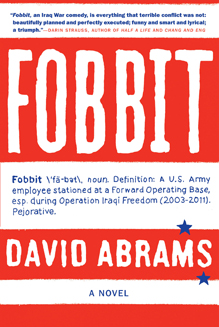

To get around the issue of being too much in war, even the most combat-intensive novels step out of it. Whether Joseph Heller’s “Catch 22,” Richard Hooker’s “M*A*S*H*” and Karl Marlante’s “Matterhorn,” they take a narrative stance that sometimes puts the reader near the war but not always deep in it. That’s the idea of David Abrams’ “Fobbit,” set at a forwarding operating base, or FOB, in Baghdad, Iraq, during Operation Iraqi Freedom. It’s not quite the Green Zone but not quite Fallujah, either. Published last year, “Fobbit” has drawn praise from reviewers. Christian Bauman of the New York Times called it “a very funny book, as funny disturbing, heartbreaking and ridiculous as the war itself.”

As part of a series of Veterans Day talks at the Kachemak Bay Campus, Abrams visited Homer last Thursday for a reading and craft talk. The college also sponsored a talk Monday on the 70th anniversary of the World War II Aleutian Campaign with military historian Col. John Cloe, Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge public programs supervisor Poppy Benson and history professor Michael Hawfield.

A 20-year military journalist, Abrams joined the Army after graduating from the University of Oregon, Eugene, with a bachelor of arts in English.

“I had student loans to pay and I had a pregnant wife,” he said at the talk. “I needed a steady job and an income.”

While he had never visited Homer, Abrams’ Army duty brought him twice to Alaska, first in 1991 with the 6th Infantry Light at Fort Wainwright in Fairbanks, and a second tour at Fort Richardson and Fort Wainwright. After retiring in 2008 from the Army, Abrams returned a third time to get a master of fine arts in creative writing from the University of Alaska Fairbanks — paid for with tuition assistance earned during his military service. He now lives in Butte, Mont., with his wife, Jean, where he teaches creative writing.

“Fobbit” comes from the Iraq War slang for a solider who serves at a FOB. Abrams served with the U.S. Army 3rd Infantry in 2005 at FOB Camp Liberty, later Camp Victory, with a public affairs team in Baghdad.

Going to Iraq was the first time Abrams had ever seen combat

“Or what I thought was combat,” he said.

Before going to Iraq, he thought he’d be living in tents and eating meals-ready-to-eat, but at Camp Liberty, he worked in a cubical jungle.

“I lived in sand-free sheets, and I was one of the lucky ones,” Abrams said. “I fully acknowledge that there were those who had it much, much worse.”

In Iraq, Abrams wrote carefully sanitized, military censored press releases about events such as weapons caches being destroyed and soldiers killed. As the civilian press saw him, he was the nameless “official Army spokesperson,” he said.

“I wasn’t the lowest man on the totem pole. I was the middle man on the totem pole,” he said.

Working from daily reports of action, Abrams would write draft press releases that would go to his bosses, get edited in red pen, and come back down to him.

“It went through this long chain of command, of authority,” Abrams said. “That was one of the frustrating things. That’s where I got the genesis for the novel — the frustration of the bureaucracy.”

Other journalists didn’t always use those releases, Abrams said.

“I had no illusions — they got the delete button and threw it out,” he said. “It was still my job. We provided information. It would trigger them to call and ask for more information.”

“Fobbit” started as Abrams’ daily journal.

“What I was doing most creatively in my time in Iraq, every night I would go back to my trailer and write in my journal, and write about what happened,” he said.

Like his own experience, “Fobbit” follows a public affairs officer, Staff Sgt. Chance Gooding Jr.

“To paraphrase the New Testament, he was in the war but not of the war,” Abrams writes in “Fobbit.”

“They cowered like rabbits in their cubicles, busied themselves with Power Point briefings to avoid the hazards of Baghdad’s bombs,” he describes the Fobbits. “Like the shy, hairy-footed Hobbits of Tolkien’s world, they were reluctant to venture beyond their Shire, bristled with rolls of concertina wire at the borders of the FOB.”

Gooding’s job was “to turn the bomb attacks, the sniper kills, the sucking chest wounds, and the dismemberments into something palatable — ideally, something patriotic — which the American public could stomach as they browsed the morning paper with their toast and eggs,” Abrams writes. “Gooding’s weapons were words, his sentences were missiles.”

While Gooding is the main narrator, “Fobbit” also is told from the point of view of Lt. Col. Eustace Harkleroad, Gooding’s boss, who writes first-person “dispatches from the front.” Combat sequences come from the viewpoint of Capt. Abe Shrinkle. Most scenes are the classic third-person, limited omniscient “God looking down” perspective, Abrams said.

“I wanted to maintain that tonal distance,” he said. “It gave me a little bit more freedom, to give the novel a tone I wanted it to have — just a little bit snarky, but not too snarky to not be patriotic as well.”

Abrams even goes a bit afield with viewpoints, writing from the perspective of an explosive ordinance disposal robot, for example, or that of a terrorist’s mortar.

When asked if he wrote his diary, and the novel it spawned, as an outlet for his conscience, Abrams said, “To a degree. Some of it was the ramblings of a high school junior.”

“I had an evolution while I was over there,” he said of Iraq. “When I got over there, I was scared and unsure. I was scared of the unknown — not getting killed necessarily — but scared of the unknown.”

Eventually he felt secure in his job, he said, and wanted to be a people pleaser. In time he became cynical, Abrams said.

“I started seeing all those repeated patterns, the cycle of war, doing the same things over and over,” he said. “Towards the end it was resignation.”

Fobbit though he was, at a forward operating base Abrams still faced danger. In the novel he describes a mortar attack on a FOB, based on an incident that actually happened. The attack hit a National Guard unit from Georgia which had an embedded reporter.

“There was a mortar that landed in the PX courtyard. It killed one person and wounded several others,” he said. “The worst part of it … They had literally arrived the day before. Welcome to war.”

“Those things happened,” Abrams said. “I made it through. I made it through so I could be here tonight.”

Michael Armstrong can be reached at michael.

armstrong@homernews.com.