Few people these days would associate the word “cosmopolitan” with Tustumena Lake, and for good reason. The lake is part of the massive Kenai Wilderness within the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge, so it’s hardly residential.

Except for structures erected on a handful of private inholdings around the lake, new buildings are not allowed. Structures still standing on land outside the inholdings are primarily public-use cabins, available for daily rental. The public lands surrounding Tustumena Lake have been closed to private human development for decades.

But federal restrictions weren’t always in place. In the last decade of the 1800s and during the first half of the 1900s, Tustumena Lake was home — mostly seasonally — to a collection of trappers and miners, living mainly along the northern shore of the lake and its upper end, toward Indian Creek, Tustumena Glacier and Devil’s Bay.

It might seem to the casual observer that most Tustumena residents in those days must have been a bunch of white, male Lower-Forty-Eighters seeking their fortune or hoping to escape from the rest of the world while experiencing the wilderness adventure of a lifetime. But the casual observer would be only partly correct.

Those former denizens of Tustumena were, largely, white men. Women, with one big exception, were almost exclusively visitors or participants in various hunting parties. That one exception was a pair of medical professionals who worked at various times out of Kenai and, on the north shore of the lake in the 1940s and 1950s, had their own recreational cottage now known as the Nurses’ Cabin.

The two women were Pennsylvania native Vera Elizabeth Liebel and Maryland-born Mary Douglas “Doug” Barnsley. Both women were nurses, and both were involved in what was called the “petticoat flying service.” Liebel was a pilot and owned her own single-engine airplane; it is unclear whether Barnsley was also a pilot.

What is more certain is that they built or helped to build the cabin for which they became known.

As for the men who populated the rest of the lakeshore, their origins were much more diverse than one might imagine. Lake residents were comprised primarily of immigrants from numerous European countries, plus a few go-getters from a scattering of American states.

Most of these men lived and worked on the lake between 1910 and about 1935, as waves of immigrants came to America, pushed westward and then headed north to the wide-open territory with its myriad opportunities for riches, land, and fresh starts.

Over the years, the most heavily represented country around Tustumena Lake was Finland, and the most well-known of the Finns was Andrew Berg, the feature attraction of Catherine Cassidy and Gary Titus’s 2003 book, “Alaska’s No. 1 Guide: The History and Journals of Andrew Berg, 1869-1939.”

According to Cassidy and Titus, Berg left his native country in 1887, a few months before his 17th birthday. Finland, at that time, was under Russian control (after centuries of Swedish domination), and Andrew was raised speaking and writing the Swedish language. Poverty in Finland drove Berg and many other Finns to seek succor in America.

Berg soon arrived in Kenai and may have begun spending winters trapping on Tustumena Lake as early as 1888. Certainly, he was one of the first men to build a home there. In fact, he built more than one home on the lake’s northern shore, plus numerous shelter cabins for his traplines all around the lake. Generally, Berg lived on the lake from autumn to spring, then moved to either Kasilof or Kenai to fish commercially and restock his winter larder.

Berg’s younger brother Emil — one of his 11 siblings — joined Andrew on the Kenai in the early 1900s. He, too, came to live on the lake seasonally. He built a two-story cabin on the north shore, living there even after Andrew died in 1939. The Berg brothers were two of the most respected and accomplished big-game guides on the peninsula.

Another early arrival at the lake was William Freeman, also a Finn. Little is known of Freeman’s history. For instance, “Freeman” was almost certainly an American-sounding name that he adopted after immigrating to the United States in about 1865. It is uncertain when he first arrived in Alaska, although he shows up in the 1900 U.S. Census as an employee of the Alaska Packers Association cannery at Kasilof.

The length of Freeman’s tenure at the lake is also fuzzy, although it definitely was brief because Freeman died in September 1906, at age 63, and was buried in the cannery cemetery. Andrew Berg’s diaries contain numerous mentions of a “Freeman Camp” on the northern lakeshore. Decades later, in that same location, there stood a structure known locally as the Freeman Cabin. Since William Freeman had already died by the time the cabin was first mentioned, the structure’s origins remain obscure.

It could be that the cabin’s name came simply from the previous existence of the well-known camp. The old identity could have persisted because name recognition made it easier for lake residents to identify. The truth of this supposition may never be fully ascertained.

During the first years of the 20th century, mining enterprises brought more men to the lake. Most of them were there for a summer or two and then were gone; others were merely speculators, arriving in order to stake claims they could either work themselves or, more likely, sell to companies that could afford to buy up groups of such claims and then invest in the equipment and personnel necessary to exploit them.

One of the earliest of these entities was the Northwest Mining & Development Company, which briefly established a mining camp near the outlet of Indian Creek, which flows into Tustumena Lake’s upper end from a watershed in the Kenai Mountains.

Boatloads of mine workers lived and worked from the camp during two or three summers before the enterprise was abandoned and the camp structures (buildings, lumber, roofing tin and lengths of pipe) were left for scavenging lake residents. Few things were left to waste. Pipes and tin, in particular, were highly prized for woodstove exhausts and for weather-proofing cabin roofs.

Yet another early Finn was Charles Nyman, sometimes called Charles Newman, who was believed by many in the area to have gone off his rocker before disappearing by 1910. Andrew Berg made frequent diary references to Nyman in the 1920s, usually through placenames associated with him — the “Nyman Coast,” the “Nyman house,” Nyman’s cabin, Nyman’s trail — but never to the man himself, indicating that Nyman was long gone.

One of Berg’s place-name references hinted strongly of Nyman’s mental state: “crazymans cannon [canyon]”. Another, later lake resident wrote in a journal that Nyman “went insane,” perhaps from “to [sic] much isolation.”

Since we have no Berg diaries from the first two decades of the 1900s, we can only assume that Berg had known Nyman personally and doubted his sanity.

In 1900, at age 25, Nyman, who called himself a miner and claimed to have immigrated to the United States in 1893, came to the Cook Inlet via San Francisco and worked in the Pacific Steam Whaling Company’s cannery in Kenai. Sometime after that, he traveled to Tustumena Lake and apparently built a cabin on the glacial outwash plain.

Some historians believe that after Nyman’s departure, his vacant, unclaimed cabin was taken over by a pair of Norwegian brothers, Ole and Erling Frostad. Over the years the structure came to be associated with the Frostads, and Nyman was largely forgotten. In about 1940, the flooding Tustumena Glacier river wiped out the cabin and washed away its existence.

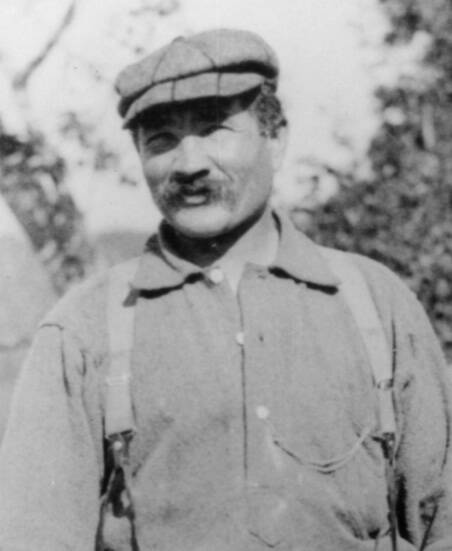

We are left with a smattering of inconclusive written evidence and two old black-and-white images: a photo showing three men at the cabin in probably the late 1920s or early 1930s, and a circa-1940 photo showing the cabin collapsing into the river current.

The Frostad brothers trapped on upper Tustumena Lake in the 1920s and 1930s and were mentioned frequently in the diaries of Andrew Berg. Ole lived on the Kenai Peninsula for many years before moving to Washington, whereas Erling lived out the remainder of his life in Alaska.