AUTHOR’S NOTE: The aftermath of the 1967 shoot-out at the Hilltop Bar and Café, near Soldotna, began to play out over the next days, weeks and months. According to victim Bill Hansen’s son, Eugene, and his daughter-in-law, Della, the results of the trials failed to come close to meting out a fair punishment to the perpetrators.

Debatable Justice

News coverage was spotty during the months between the shootout at the Hilltop Bar and Café on Dec. 11, 1967, and the trial 10 months later. Meanwhile, life continued for the four participants in the incident — but not equally.

According to Eugene Hansen, his father, Bill Hansen, was “recovering great” in the hospital in early 1968 when he suffered a severe setback — a stroke, probably caused by a blood clot, that hindered Hansen’s ability to communicate and paralyzed his right side.

Bill Hansen was moved to a medical facility or rest home in California as he attempted to recuperate, and the rest of the Hansen family attempted to keep the bar afloat in his absence. “We tried to run it for a couple of years,” said Eugene, but it was just too difficult.

By 1969, the family took on a new owner (Joe Keeney), then put the business in the hands of at least one other operator, before finally agreeing to sell out.

The two men arrested after the shooting incident — T.L. Gintz and Harvey Dale Hardaway — were indicted by a grand jury on three counts: assault with a dangerous weapon with intent to kill; assault with a dangerous weapon against Hansen; and assault with a dangerous weapon against Hansen’s cook, Marshall Dorsey. Their trials ran during consecutive weeks in October 1968 in Anchorage Superior Court.

Bill Hansen’s poor health prevented him from traveling to Alaska to testify. Prior to the trial, a State Trooper had traveled to California to conduct an interview with Hansen, telling him to nod in the affirmative or shake his head in the negative to the questions he posed. The officer recorded the audio from the interview, including his explanation of Hansen’s responses.

Prosecutors attempted to enter the recording as evidence, but the judge disallowed it because Hansen’s own voice could not be heard on the tape.

Furthermore, the prosecution had no other reliable witnesses to present to the court. Eugene Hansen said Dorsey would not testify, but it is more likely that he simply took the stand and declared himself unable to remember the event because he had been knocked cold when a bullet grazed his forehead. Another apparent witness (unidentified in a Cheechako News article about the trial) could not be located.

With no word from Bill Hansen and no evidence from Marshall Dorsey, the jury was left to sort out the testimony of the two accused men. The presiding judge dismissed the “intent to kill” charge in both trials on the grounds of insufficient evidence.

Eugene Hansen, who was sitting in the courtroom, burst out in anger: “I said, ‘So, in other words, you can get away with murder in this state!’ And (the judge) said, ‘Another word and I’ll fine you for contempt of court,’ so I didn’t say any more.”

“We were very upset, very upset,” said Eugene’s wife, Della, who was also in attendance.

Hardaway was found guilty of assault on both Hansen and Dorsey, while Gintz was found guilty of assault only against Dorsey. Testifying on his own behalf, Gintz claimed that he had only started a fistfight and that he had been unconscious when the shooting started. The maximum allowable sentence for each guilty count was a $500 fine and six months in jail.

How long each man spent behind bars is unclear. Perhaps they each got off with a fine and time served. One thing is certain, however: Six weeks after his sentencing, Hardaway was a free man.

On Dec. 2, 1968, Hardaway and nearly 40 other passengers boarded a Wien Consolidated Airlines turboprop bound for the village of Iliamna. About 15 minutes from landing at its destination, the plane crashed into frozen Foxes Lake, killing all aboard.

A welder-pipefitter employed by Perco Corporation, in Anchorage, Hardaway had been 37 years old. He was survived by a wife and two children in Seattle, as well as his parents in Kansas and two siblings in California.

Gintz, who was four years older than Hardaway, had married Doris Elaine Fuqua in Louisiana in 1954. They had had four children in six years before Doris died in 1960, at age 31.

In February 1969, Kenai magistrate Jess Nichols issued an arrest warrant for Gintz, a member of the Tulsa (Oklahoma)-based Local 798 of the Plumbers and Steamfitters Union, for failing to appear in court for a hearing on assault charges which Gintz himself had filed against two members of a rival, Anchorage-based union, Local 367. Members in both locals, said the Anchorage Daily Times, had been “locked in a bitter dispute for months over a local-hire issue on a pipeline construction job in the Kenai area.”

Judge Nichols dismissed Gintz’s charges. Subsequently, similar charges were filed against Gintz.

Despite such troubles, Gintz survived for another three decades, dying in 1999 in Alabama at the age of 71.

Bill Hansen, who never fully recovered from his injuries and his stroke, died in March 1984 in Roseburg, Oregon. He was 85.

Epilogue

No bar stands today north of the Sterling Highway and across from the Birch Ridge Golf Course. The ghosts of Ann Pederson and Jack Griffiths, once said to have haunted the establishments there, have been quieted.

But five more decades of activity occurred at that site before the State Department of Transportation, preparing for safety improvements, razed all the structures and cleared away the trees, brush and debris closest to the highway.

Joseph Franklin Keeney, a former commercial fisherman and truck driver, was in charge of the Hilltop in 1969. A brief notice in the Anchorage Daily Times called Keeney the owner.

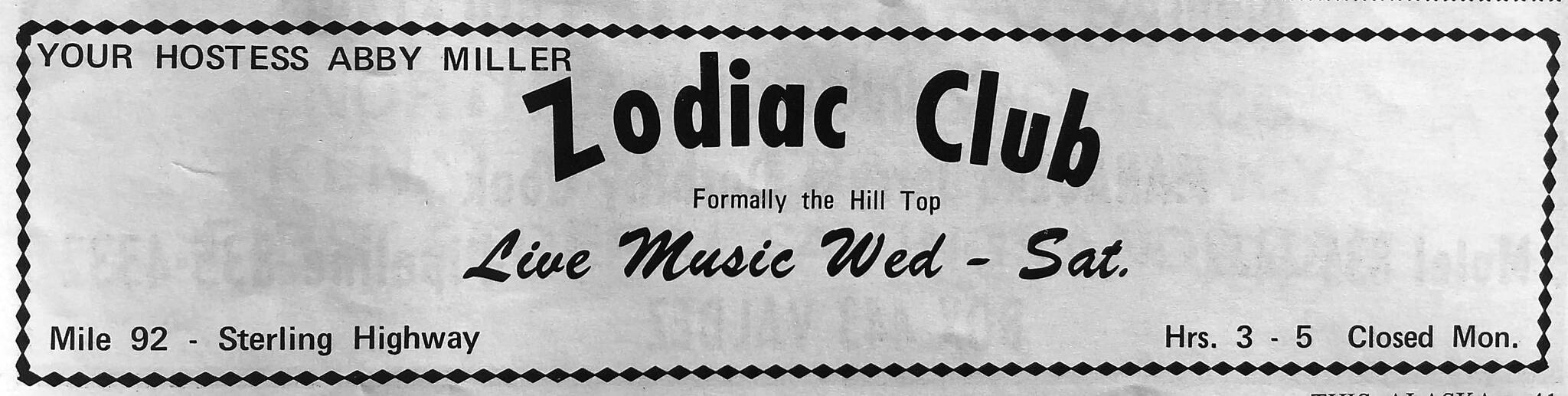

By the early 1970s, however, a man called Mike Baugh appears to have been the owner and operator of the establishment. He renamed the place the Zodiac Club, featuring Abby Miller as his hostess.

A former Zodiac Club patron described the interior this way: “The inside was painted black, and there was a galaxy and zodiac theme painted in UV paint on the walls and ceiling and was lit up with blacklights. Basically, it was like a big blacklight poster on the inside. Very dark in there.”

Baugh’s ownership proved problematic, as alleged illegal activities frequently drew the attention of law-enforcement officials. The Zodiac was part of a 1973 drug raid, and Baugh was arrested. By 1974, Baugh was out, and ownership of the bar and its liquor license had reverted back to the Hansen family.

According to the next owner, Charles Cunningham, who renamed the bar again and launched his own business there in late 1974 as Good Time Charlies, Baugh had been a convicted felon and should never have qualified for a liquor license in the first place.

Cunningham paid the Hansens $62,000 for the bar and the lot on which it stood. After a $5,000 down payment, he paid monthly installments of $600, plus 7 percent interest, for the first two years and then $800 a month after that.

Before he opened the doors of his new place, Cunningham and his brother-in-law Lee Grady Thomas performed many weeks of refurbishing the interior and making it more aesthetically pleasing. One of the big changes involved removing the Zodiac’s large indoor fire pit and air-exchange system and replacing it with a fireplace and a dance floor.

Cunningham owned and operated his bar for nearly 50 years before an agreement he had made with the state in 1991 prompted him to close down in 2022 and gut his business before the state took over.

During the heyday and demise of the Zodiac Club and the subsequent rise of Good Time Charlies, plenty of action was taking place across the highway on the larger portion of the former Jack Keeler homestead.

Under the ownership of Thomas and Gail Smith, a golf course and camper park were taking shape. Heavy-equipment operator Charles Foster cleared the land for the fairways, tees and greens, campsites, parking lot, and the Smith home, and in May 1974, after two years of work, the Birch Ridge Golf Course and Camper Park opened for business.

Stray golf balls from the ninth fairway caused occasional problems with the vehicles of bar patrons, according to Cunningham, and his personality clashed at times with Tom Smith, who had been interested in the bar property himself for a sort of “tenth hole” for his own customers.

But the two businesses managed to coexist for nearly five decades.

Except for the bar, the former Jack Keeler property north of the highway, was purchased in the 1960s by Edward J. Call, the half-brother of Boyd Miller, the man who, behind the bar in 1961, had found the body of Ann Pederson after her suicide and who had escorted Jack Griffiths to his home before Griffiths was beaten to death by Jim Bush.

Call’s obituary in 2010 charitably described his passion for collecting “good junk.” As a result of this passion, the property contained abandoned vehicles and a scattering of buildings, including some of which had been deteriorating for as long as many passers-by could remember.

Longtime residents also recalled a serious fire on the bar property. According to Cunningham, the source of the fire had been a house trailer parked out back for the benefit of his bartender/manager Candy Wade.

No one had been injured in the blaze, but the trailer was destroyed — except for the frame, which was hauled off by Ed Call and added to his collection of good junk.