AUTHOR’S NOTE: The jury in the Jim Bush murder trial would soon have a decision to make. Bush did not deny killing Jack Griffiths in October 1961, but he claimed to have had no choice in order to protect himself.

Conflict

After the Oct. 8, 1961, confrontation between Soldotna residents James Franklin “Jim” Bush and John Edward “Jack” Griffiths, one was dead and could never tell his side of the story. The other, at a murder trial seven months later, was hoping an Anchorage jury would believe that the killing behind the Circus Bar had occurred in self-defense.

In mid-trial — late May 1962 — local homesteader and oilfield worker Boyd Miller took the stand. Miller had also played a part in the investigation of another 1961 death behind the same bar. He was the man who had discovered the body of Ann Pederson, who had been living in a trailer there and had taken her own life.

Now, he was sitting on the witness stand and describing how, at about midnight on Oct. 7, he had escorted a highly intoxicated Jack Griffiths home from the bar on the eve of Griffiths’ demise.

According to the Anchorage Daily Times, Griffiths had been “in pretty rough shape,” so Miller sat with him on Griffiths’ bed and talked with him for a while. Miller testified that, during this time, he spotted an M1 military rifle on another bed nearby. Miller said he picked up the weapon and, performing a “manual of arms” check, found it unloaded.

“I just snapped it,” Miller said, “and threw it over onto the other bed.” The prosecuting attorney showed Miller a crime-scene photograph that depicted Griffiths dead on his bed and the rifle near his legs. “Not where I left it,” Miller responded, referring to the firearm.

After leaving Griffiths alone in his bed, Miller said he returned to the bar. There, he spotted Jim Bush, who had recently been driven back to the bar by a friend.

When Bush himself took the stand, he described his own visit to Griffiths’ home that night. He testified that he had knocked on Griffiths’ door and been told to come in. From the Anchorage Daily Times: “Bush quotes Griffiths as saying, ‘What the hell do you want?’ to which he responded with ‘Jack, what’s the matter?’” Bush claimed that Griffiths then swung a rifle in his direction and said, “I ought to blow your head off.”

“It flashed through my mind,” Bush testified, “(that) Jack was so drunk that he might try to kill me…. He had a dazed look, wild look.” Despite this concern, Bush said, he had no plan to kill Griffiths. Instead, according to the paper, “he snatched a piece of firewood, lunged at Griffith, pushing aside the rifle with his right forearm and striking Griffiths over the head with the wood in his left hand.”

“Jack fell back a little ways, started to come up again, and I hit him again,” Bush testified. He said Griffiths fell back and dropped the rifle. Bush then dropped the wood back on the woodpile, turned off the lights in the Quonset, and departed.

Aftermath

After Griffiths’ body was discovered, Dorothy Foss, wife of one of the men who now owned a share of the Circus (renamed the Hilltop Bar and Café), drove to Kenai to inform Griffiths’ family of his death. During the previous evening, an angry Jack Griffiths had ordered Jim Bush to leave his home and had then kicked out his wife and their children. A friend had offered the Griffiths family a cabin in Kenai in which to stay.

Foss testified that when she arrived at the cabin, she noticed that Jim Bush was there, “standing with his arms around Delores,” Griffiths’ teenage daughter whom he had been dating for four months.

Final arguments in the trial occurred May 31, 1962. Assistant district attorney Clyde Houston referred to Bush as a “highly intelligent, cold-blooded man” and called his version of events “a lie.” Defense attorney Wendall P. Kay, on the other hand, contended that Bush had killed in self-defense when Griffiths had threatened him with a gun.

The jury required only nine hours to deliberate the case, reaching a verdict at about 3:30 a.m. on June 1. They found Bush guilty of the lesser charge of manslaughter, which carried a sentence of five to 20 years.

At the sentencing on June 15, Superior Court Judge Edward V. Davis gave Bush 12 years in prison. “It disturbs me that even to this day you have shown no remorse over the killing,” said the judge. “You’re not an executioner for the state of Alaska or anyone else…. You didn’t even have the decency to tell the family what you’d done.”

The Youth and Adult Authority then argued against providing Bush any opportunity for probation. The prosecution argued that Bush’s prior criminal record indicated that he could not be trusted.

Bush himself contended that he could still be a productive member of society, and the Rev. Walter Rush attested to Bush’s good character and asked the court for leniency.

Although he unsuccessfully appealed his conviction in 1964, Bush did earn parole and an early release by the early 1970s.

Bush married three more times and had several more children. For about a year in the mid-1970s, he moved back to his home state of California and operated a gas station in Taft, the town in which he’d been born. After returning to Alaska, he became a heavy-equipment operator and a long-haul trucker working out of Prudhoe Bay during the pipeline construction years.

By 1990, he had completed his final divorce and had been living back in Kasilof for about a decade. He continued to live there after his retirement, and he died on his 79th birthday, in 2018.

By January 1963, Alice Griffiths had remarried. Her new husband was Boyd Miller, the man who had escorted Jack home on the night he was killed.

Alice died in July 1974 at her home on Mackey Lake Road in Soldotna. Buried next to Jack in the Kenai City Cemetery, she was survived by her son and five daughters—all adults who were either married or had been. Her parents and her brother were still living in California.

Shortly before Jack Griffiths’ death, the bar had begun operating as the Hilltop. The Hilltop’s grand opening had actually taken place in early September with the bar offering a free three-day barbecue. The changeover from Circus to Hilltop became official, however, in late October — about three weeks after Griffiths’ death — when the Circus liquor license was transferred to the Hilltop’s co-owner, Arthur Alvin “Swede” Foss.

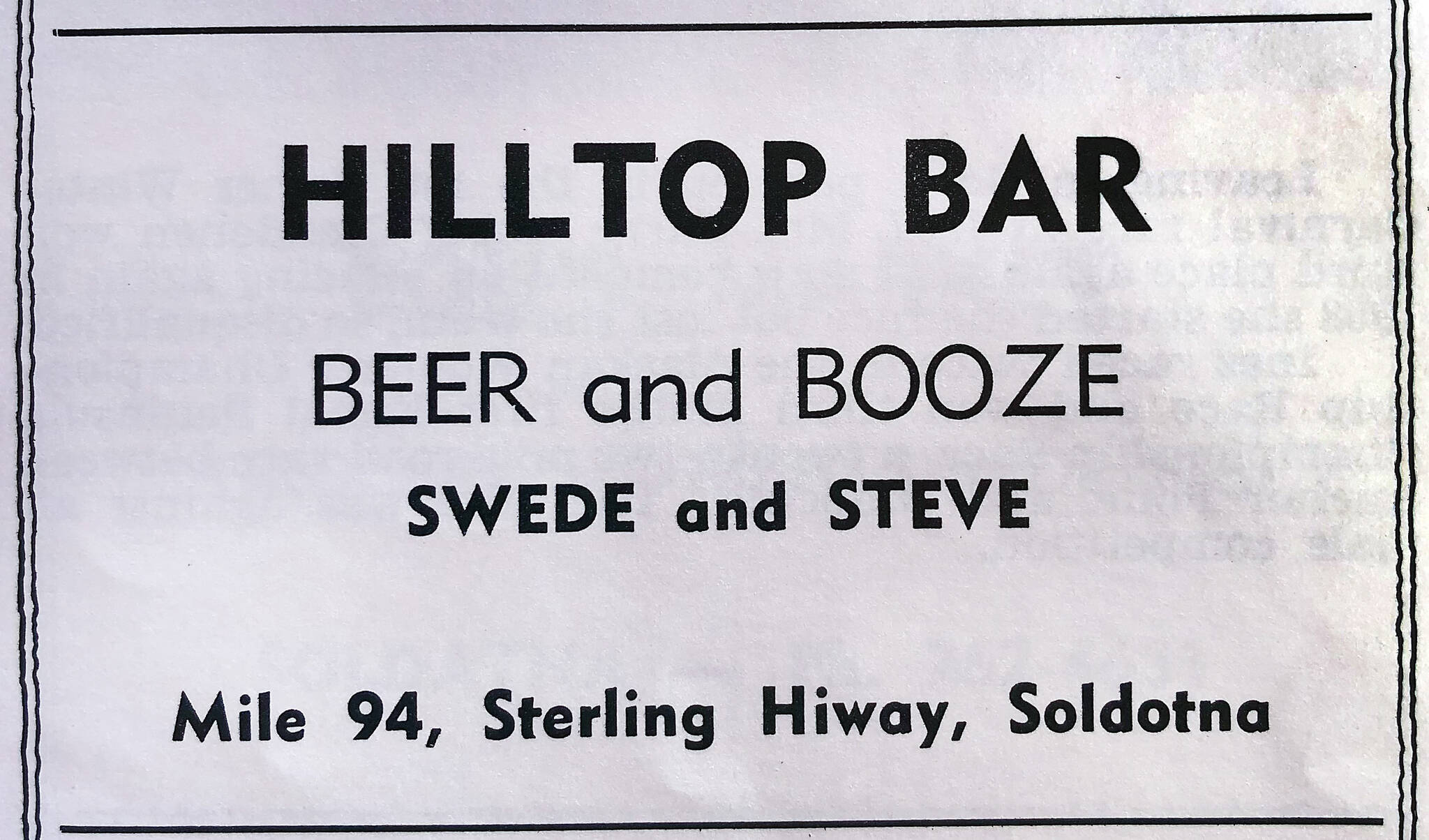

A 1962 advertisement in the Anchor Point Snow Festival program promoted “Beer and Booze. Swede and Steve, Mile 94, Sterling Hiway, Soldotna.” The name “Steve” almost certainly referred to Steve Henry King, a co-owner of the Circus Bar mentioned frequently in coverage of the Griffiths investigation and trial.

Those were headier, happier days for the new bar, but more violence was on the way.