Forget all those interlocking pieces, hard to wrap shapes and battery-needing games. Here’s an activity that’s ancient, international and entertaining: string storytelling, as demonstrated recently at the Homer Public Library by David Kitaq Nicolai.

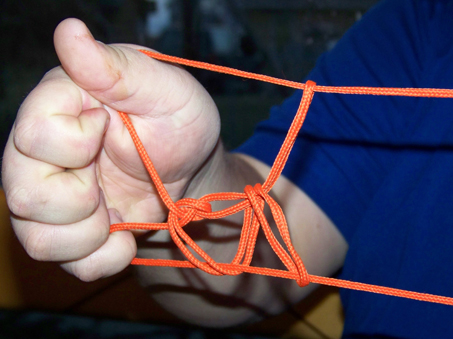

Nicolai’s hands flew as he looped, stretched and twisted his orange, six-foot nylon rope around and between his fingers. Most of the time, his well-trained hands seemed to move on their own while his twinkling eyes focused on his audience and he told the story his hands were illustrating with string.

Here a fox. There a whale’s tale.

Only occasionally was Nicolai silent as he slowed his pace and focused on his fingers as they wove intricate patterns that told his stories.

Nicolai, 29, is of Yup’ik, Athabascan and French Canadian descent. He was raised in Anchorage, graduated from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y., and, since 2007, has lived in Anchorage, where he works as a mechanical engineer.

At 12 years old, Nikolai began copying what he saw his father and his father’s mother do.

“She had probably 85 good stories,” said Nikolai of his grandmother’s repertoire. However, she knew them so well that she was sometimes “unable to go slow enough” for Nikolai to learn them. Still, he estimates his own storehouse of stories includes 45-50 different tales.

While most of his learning came through observation, some came through elders who would subtly let Nikolai know if he was correctly following tradition. “Hmm, I never heard it told that way,” an elder might say, suggesting there might be another way to tell a story.

By the time Nikolai was 16, he was performing publically. Sometimes it was with his father, Matthew David Nicolai. Sometimes he has been a one-man-show, like he was at the Homer library. He and his father have performed at the Alaska Native Heritage Center, the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., at various school events for the Anchorage School District and a private audience for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito in Anchorage.

On his own, Nikolai and his loop of string have entertained at AHNC, Alaska Native Charter School, various school events for Brunswick Central School District in New York and the Anchorage School District, at Anchorage Public Library events and with Ignite Anchorage, a community forum for sharing knowledge and information.

Nicolai also is a contributor to “Native Alaskan String Figures,” a book on the subject by David Titus and available at the Homer Library. It includes everything from how to get started to an assortment of shapes illustrated by Amanda Boehm.

The book also offers a historical perspective.

“String figures have been made by people of the North for longer than anyone can remember. They have been around for hundreds, maybe thousands of years,” Titus writes in the introduction, reaching beyond Alaska to include Siberia and Canada.

“When first contact was made with these people from the outside, they were already making these figures in all areas of the north. Maybe they had different names for them, or only knew part of the figure, but they were very popular.”

The book includes rules adhered to in some cultures: children are never taught the figures; most figures are accompanied by a chant, poem or story; string figures were only made in the winter.

While Nicolai’s fingers worked through stories, he suggested a source for an even broader perspective of string figures: the International String Figure Association, based in California. It’s founders are Hiroshi Noguchi and Philip Noble. Noguchi is a Japanese mathematician; Noble is an Anglican missionary in Papua, New Guinea. The not-for-profit group’s goal is to perpetuate the enjoyment of string figures by gathering, preserving and distributing information from around the world. The ISFA’s web site includes links to information on the subject from Japan, Israel and France, and a figure-of-the-month page with step-by-step video clips. According to Nicolai, string figures from the arctic and sub-arctic are deemed the ISFA’s most-difficult-to-construct.

As recently as five years ago only a handful of Alaskans could tell stories the way Nicolai does; however, the interest is growing, thanks, in part, to Nicolai.

“With my work I travel to villages a lot and I stop at schools and ask if they might be interested in five minutes of storytelling,” he said, noting how five minute shows frequently lengthen and the audience tends to grow. “The kids love it.”

Nicolai’s visit to Homer was part of the “One Hundred Year Celebration” of the Alaska Native Brotherhood and Alaska Native Sisterhood Traveling Exhibition that was at the library during the month of November.

McKibben Jackinsky can be reached at mckibben.

jackinsky@homernews.com.