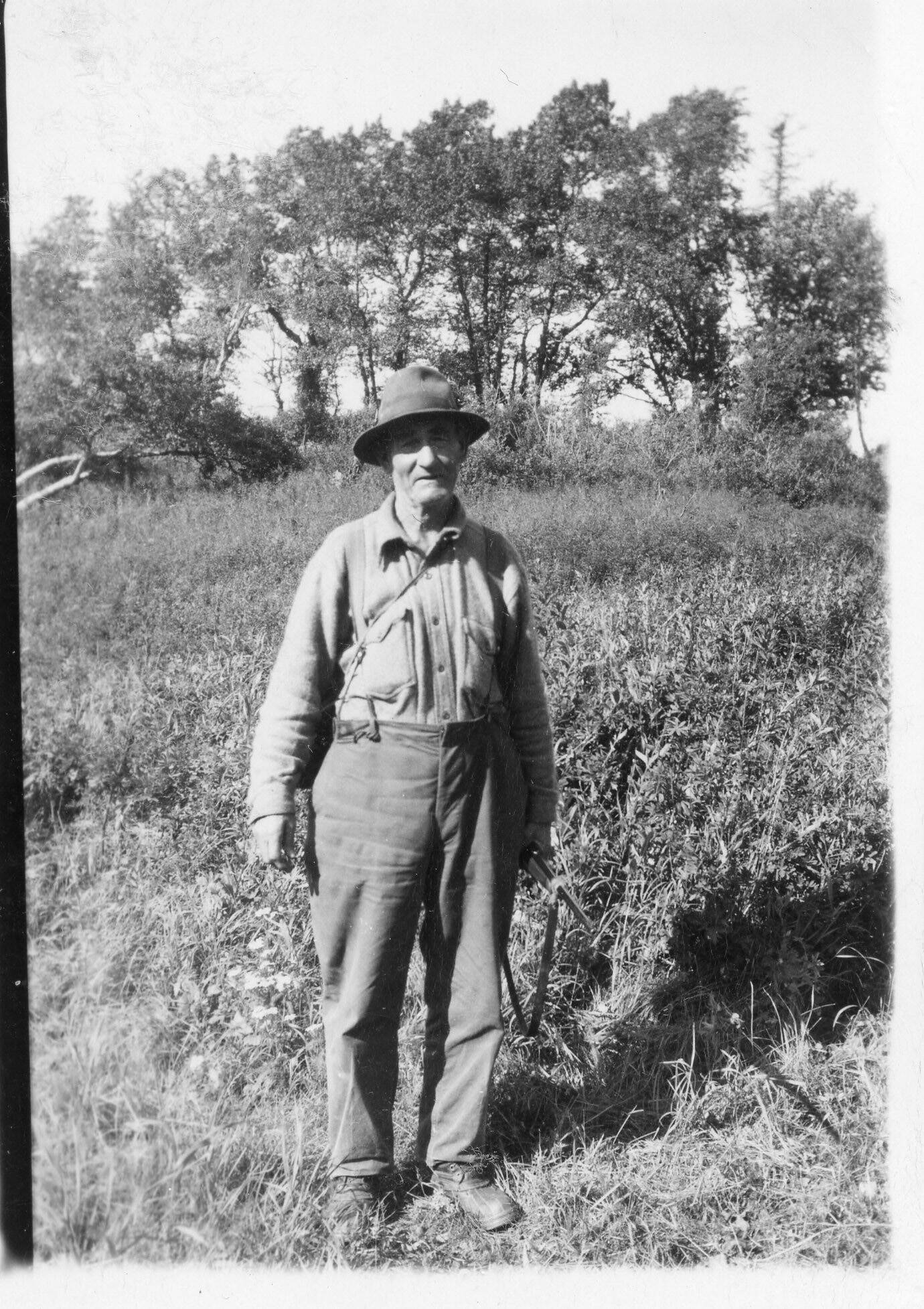

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Thirty-five-year-old Rex Hanks homesteaded in the Happy Creek valley in 1946. He remained a bachelor until 1953, when he married registered nurse Irmgard Matz in Seward. Together they had two daughters, both stillborn. Rex built a modest home for himself and his wife south of the creek and near the beach above Cook Inlet.

Of Geese and Men

One autumn in about 1950, Happy Valley homesteader Rex Hanks was waterfowl on the Ninilchik flats, which he said were thick with geese that day. He took a shot at a goose in the air. His aim was true, and the bird began plummeting earthward. As it fell, it happened to strike another goose that had been trying to jack itself free of the ground.

When Hanks hurried over to collect his kill, he found that the goose that had been on the ground had suffered a broken leg. For Hanks, one goose for his pantry was plenty. He packed up the dead bird and took the injured goose home. Throughout the winter, he nursed it back to health.

“When the spring migration began and the geese were going north,” he recalled in The Pioneers of Happy Valley, 1944-1964, “I took my goose down to the flats and left him among the feeding birds.”

Rex Hanks had a reputation as a forthright, hard-working, inventive and sensitive man.

He believed that neighbors should help neighbors. So he shared produce from his garden. He cut house logs and lumber for newcomers building new homes. He helped prospective homesteaders locate available parcels. He assisted with digging basements and water wells.

But sometimes difficult choices were necessary. At one point, he agreed to help a neighbor hand-dig a water well but had to stop before the job was finished. The neighbor, Hanks said, refused to crib the walls of his well, even though cribbing was a common safety practice. Eventually, Hanks couldn’t stand it any longer and left the neighbor on his own.

“I told him I did not want to be a part of his death,” Hanks said. “I worried more about him than he did.”

When Hanks first moved to his Happy Creek property in 1946, he set up a sawmill business that began below the falls at the mouth of the creek. He ditched creek water around the falls and into a trough that led to a Pelton wheel that powered the mill. In order to bring finished lumber from the mill to the top of the bluff after the Sterling Highway had been pushed through, he built a small steam engine that powered a trolley to do the work.

“The remains of the trolley system were also a great source of entertainment for the local kids,” wrote Shirley Schollenberg in her Happy Valley chapter for Snapshots at Statehood. “It consisted of a 55-gallon barrel attached to cables. Kids would go to the top of the trolley, get in the barrel and ride it to the bottom.”

Viola Hansen, whose father, Torval Jensen, was an early settler in the area, recalled in The Pioneers of Happy Valley that Hanks seemed to enjoy the company of the local kids. “When my brother and I were younger,” she said, “we used to go from dad’s fish trap up the beach to Mr. Hanks’ place. He would make us cocoa and give us cookies. Then he would play the violin for us. He was very good on it.”

He was a man of many talents.

On one of his trips back to his home state of Washington, Hanks built a 60-power, reflector-style telescope and brought it back to Alaska. “I loved to study the moon, stars and planets,” he said.

Neighbor Wayne Jones claimed that Hanks had even ground the glass for the device. “He was interested in astronomy,” Jones said, “and many of us would use (the telescope) on clear nights. Rex would always explain the planets and what to look for.”

“It was amazing what he could do,” said Clovis Kingsley, another Happy Valley pioneer. “He was a fine man.”

In addition to spreading his love of the firmament, he enjoyed photography and sharing his images with neighbors whom he thought would appreciate having them.

“I had two cameras,” Hanks said. “I took lots of pictures, that is if I had the money to buy film.” His longshoreman job in Seward gave him some financial flexibility, allowing him to even buy color slide film on occasion. “I gave a lot of the pictures away to the early homesteaders that didn’t have a camera or the means to buy film,” he said.

And then there was his woodworking. The hobby he’d begun during his days in Seward became a business once he and his wife, Irmgard, moved to Happy Valley.

“I began in earnest to work at it,” he recalled. “(My wife and I) roamed the forests for wood burls … to make large and small bowls, lamp bases and other odd articles…. My wife was very good about helping me put the pieces together, wrapping them carefully in large or small packages. We sold them all over the state and (in) Canada. When the first ferry ship left Alaska on its maiden voyage, they displayed some of my wood carvings on it. We didn’t make much money from it, but it helped.”

To further supplement their income, Irmgard Hanks, a registered nurse, worked for a while at the hospital in Homer. Rex took temporary jobs on local fish traps or wherever else he could find employment.

Legacy

Earlier pioneers of Happy Valley—and other parts of the southern Kenai Peninsula—did what they had to do to get by. Neighbor Wayne Jones remembered that Rex Hanks—years after moving his sawmill operation up from the beach—found an old liquor still on Happy Creek. Indeed, such ventures may have been how Happy Creek and nearby Whiskey Gulch got their names.

“We all heard the stories about the stills in Happy Creek and Whiskey Gulch,” Jones said. “I guess there was some type of liquor to be had in both places…. Some of the young men in Ninilchik used to tell some wild tales about getting booze at Happy Creek and bringing it back to the village for parties.”

Jones also recalled many people in the area talking about the possibilities of gold mining on the beaches and in the streams. “When Rex Hanks had his sawmill on the beach,” Jones said, “he always had a few flakes of gold. He picked it out of the cliffs. Maybe he got some from the sand. I heard he did.”

“I used to dig some small flakes from the rock around the sawmill on the beach,” Hanks admitted, “but it was never more than a few flakes. I never had any to sell, and I never heard of anyone in this area that did. Many of us tried the beaches, but what we found was not gold, but good-eating clams.”

Irmgard Hanks died March 1, 1984, at the age of 67. She was interred in the Anchor Point Cemetery, and her military grave marker identified her as a second lieutenant (nurse) in the U.S. Army during World War II. Rex died four years later at the age of 77 and was buried beside his wife. Also a member of the U.S. Medical Corps, his marker identified him as a sergeant during the war.

Near the resting place of Rex and Irmgard are the three white wooden markers for their two stillborn daughters and the stillborn daughter of Irmgard’s sister, Gertrude.

At some point after both Hankses had died, a new street sign was erected near mile 144.5 of the Sterling Highway. The sign, announcing Hanks Mill Road, led to Rex’s old homestead and the waterfall at the beach. That land has since been purchased by an investment company, and public access to the falls has been blocked.

The remains of Rex’s original homestead cabin is disappearing, slowly subsumed by the encroaching vegetation.