A Premise to Explore

AUTHOR’S NOTE: On Jan. 3, 2010, as I was exiting the Fred Meyer store in Soldotna, I encountered a former Kenai Central High School classmate who had been reading my articles on Kenai Peninsula history and had a suggestion for me: Try writing about a villain for a change.

He recommended a man named Jackson Ball, calling him “a real bad-ass” who he said had caused lots of problems in the Kenai-Nikiski area in the mid- to late 1950s.

The former classmate called Ball a bigot and said he basically terrorized people who were ethnically different from himself. He provided the names of people I could speak with who could verify Jackson Ball’s bad character, and he urged me to look into it.

First, I had never heard of Jackson Ball. Second, I try never to accept any single characterization as gospel. I decided to do what I frequently did back then — and still do today: I began to ask around, starting with people who’d been in this area for a while.

I emailed Al Hershberger, who had lived on the Kenai since the late 1940s. Al had known Ball personally. He wrote back: “I think his notoriety was somewhat embellished…. I guess it would be fair to call him a bigot, or at least very outspoken and vociferous…. He did not like newcomers (to Alaska) and frequently told them to ‘go back to America.’ … A lot of people thought of Jackson [as] more of a clown than a terrorist…. If I had to describe Jackson Ball with one word, it would be ‘colorful.’”

Hershberger continued: “I would not characterize him as a bad guy. He was a character who on occasion did questionable, and sometimes bad, things. He hit a guy over the head with a bar stool one time (in the 1950s) and was charged with assault with a dangerous weapon. The jury found him not guilty, saying a bar stool was not a dangerous weapon.”

“I did enjoy talking with [Jackson],” Hershberger added, “as he always made me laugh.”

In the history compilation “Once upon the Kenai,” Lillian Hakkinen referred to Ball as one of “the people I got to know and like, regardless of their lifestyles.”

In the same book, Sheryl House Martin, like Hershberger, called Ball “colorful” and remembered Ball’s mother, Margaret, as her attentive, influential babysitter.

I was intrigued — mostly by the notion that writing fairly about the life of Jackson Ball might not be a straightforward task, that creating an accurate portrayal might lead me in unexpected directions, and that, in the end, I might find myself seeking pieces to an incomplete puzzle and wallowing in ambiguity. Still, the challenge was alluring.

The article you are about to read comprises the third time I have written about Jackson Ball — but the first time in more than a decade. My first revision was compelled by new information that caused me to recalibrate what I had thought I knew.

I have also come to more fully realize just how difficult it can be to define another human being.

Turbulence

On June 25, 1935, in Old Mystic, Connecticut, 52-year-old George C. Ball was among other laborers picking strawberries on the Willow Spring Farm when a thunderstorm arrived. As the workers hurried for shelter, Ball joined a group that ducked under an open shed with a corrugated metal roof.

As they huddled together, a bolt of lightning struck the roof, split two of the shed’s supporting posts and appeared to pass directly through the body of George Ball, burning him badly on one temple and ripping one of his shoes as its charge passed into the ground. Ball was killed instantly.

A woman from Waterford also died in the incident, and six others were injured. George Ball, of Westerly, Connecticut, had been the father of seven children, including 12-year-old Arlon Elwood “Jackson” Ball.

George Ball, a veteran of the Spanish-American War, had been born in Rhode Island in 1887 and had married a Scottish immigrant named Margaret A. Skinner in about 1914. In 1930, as their young family grew, George labored as a landscape gardener on a private estate. Perhaps it was the financial straits of the Depression that cost him that job and had him picking fruit to earn money only five years later.

Or perhaps it was his criminal activity earlier in the same year of the lightning storm.

In April 1935, two months before the storm, Ball was one of three adult men convicted and fined for stealing property from the New Haven (Connecticut) Railroad. His 20-year-old son Robert also reportedly played a part in the theft but had his penalty suspended.

After George Ball’s death, other family fracture lines began to appear. Robert was dinged for a minor traffic violation, but the biggest cause for concern appears to have been the second-eldest daughter, Esther.

In January 1936, while on parole from a facility for wayward girls, 16-year-old Esther violated the terms of her release. Caught hiding at the home of relatives, she was arrested by local police and returned to the institution. By the time of the 1940 U.S. Census, her life had not improved. Esther was a 20-year-old inmate at the Connecticut State Farm and Reformatory for Women.

As a young farmhand, meanwhile, Jackson Ball was hoping that 1940 would be the start of a better life. Undaunted by having only a grammar-school education, Jackson joined the U.S. Army. According to his military record, he enlisted in September at age 19. In reality, he probably had just celebrated his 18th birthday.

His draft-registration card says that Arlon Elwood Ball was born Aug. 24, 1921. The Social Security Death Index corroborates that date; however, Aug. 25, 1922, appears on the military plaque on his grave, and one of his daughters in 2012 confirmed that the later date was correct.

Regardless, Jackson Ball — and no one still living in his family could recall the origin of his nickname — escaped the East Coast and began to establish an identity apart from his family.

Standing 5-foot-6 and weighing 139 pounds at the time of his enlistment, Ball started as an Army private. He became a Private First Class and a member of Battery E of the 243rd Coast Artillery Corps. He served overseas for two and a half years, during which he was involved in some intense fighting.

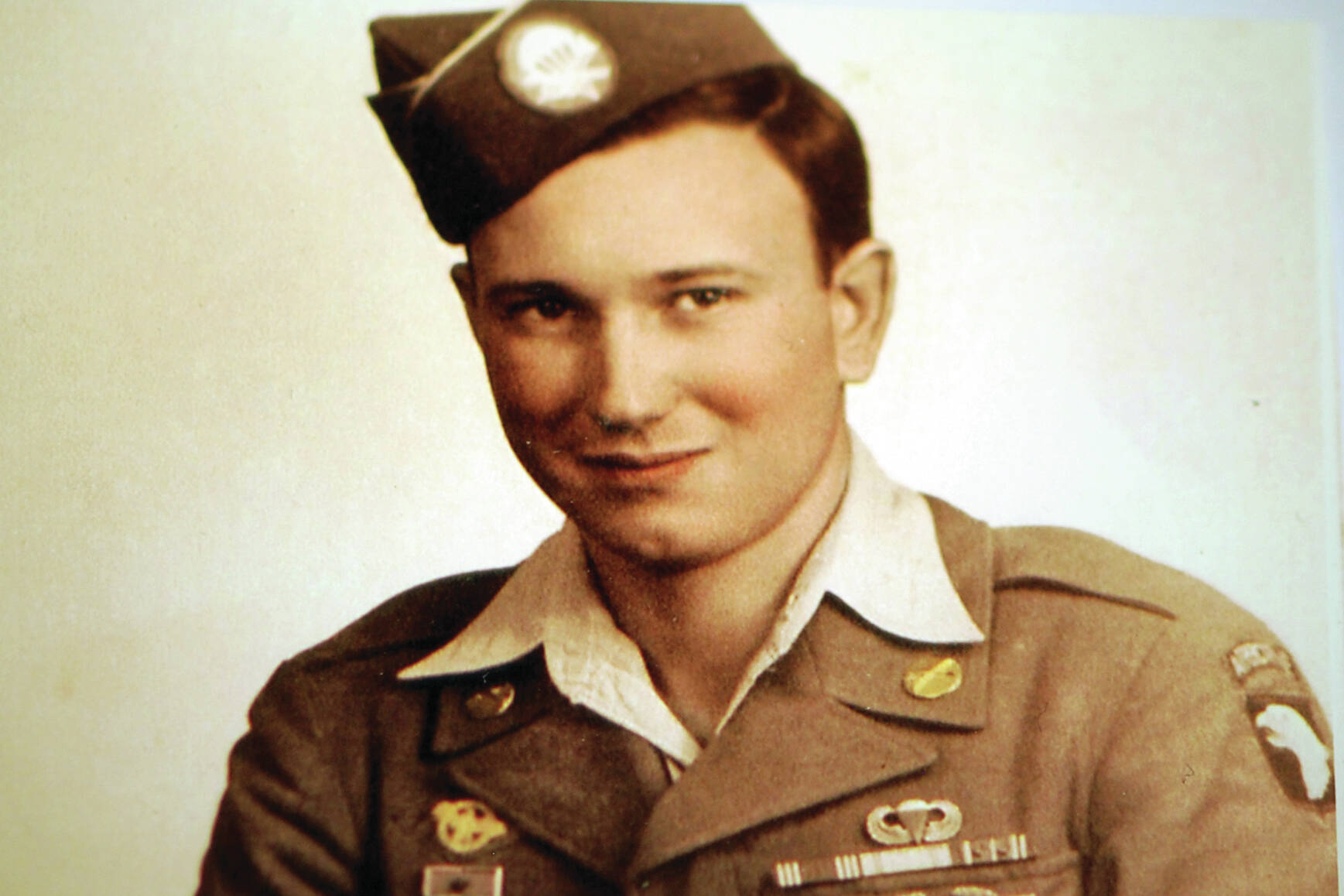

When he was discharged in 1945, he was 2 inches taller and nearly 40 pounds heavier. He posed for a portrait in dress uniform, with his many military citations on full display. On his left shoulder was a patch for the Screaming Eagles (101st Airborne). On his right breast above the pocket was a patch nicknamed the “ruptured duck,” which was sewn onto the uniforms of World War II veterans who were honorably discharged.

Below the ruptured duck patch was a Presidential Unit Citation pin, awarded by the president for distinguished action by a soldier’s unit. On his left breast were his paratrooper wings, presented after a specific number of qualified jumps. Below the wings was a strip of ribbons that represented other medals earned by Ball, including an award for good conduct, the WWII Victory Medal, and the European African Middle East Campaign Medal.

According to Al Hershberger, a former World War II veteran who also served in Europe, the two stars on Ball’s campaign medal indicate the number of battles in which Ball fought. In the nearly monochromatic portrait, it is difficult to distinguish the colors of the medals, but a bronze star indicates a single battle and a silver star indicates five battles. Based on his knowledge of the history of the 101st Airborne, Hershberger believed it likely that Ball earned one bronze and one silver star.

Finally, a pin below the ribbons was the Combat Infantryman’s Badge, awarded after 30 days of infantry combat.

Curiously, Ball, in the photo, is also wearing a wedding ring. Most people who would come to know Ball in Alaska would be aware of only his 1959 marriage to Mary D. Sullivan (nee Wood) and the four daughters they had together.

But when the portrait of Ball was taken, his union with Mary was more than a decade in the future.

In about 1950, Ball moved to Alaska. Eventually, two of his siblings and his mother would also come to live on the central Kenai Peninsula. For two of these four individuals, their time on the Kenai would end in tragedy.