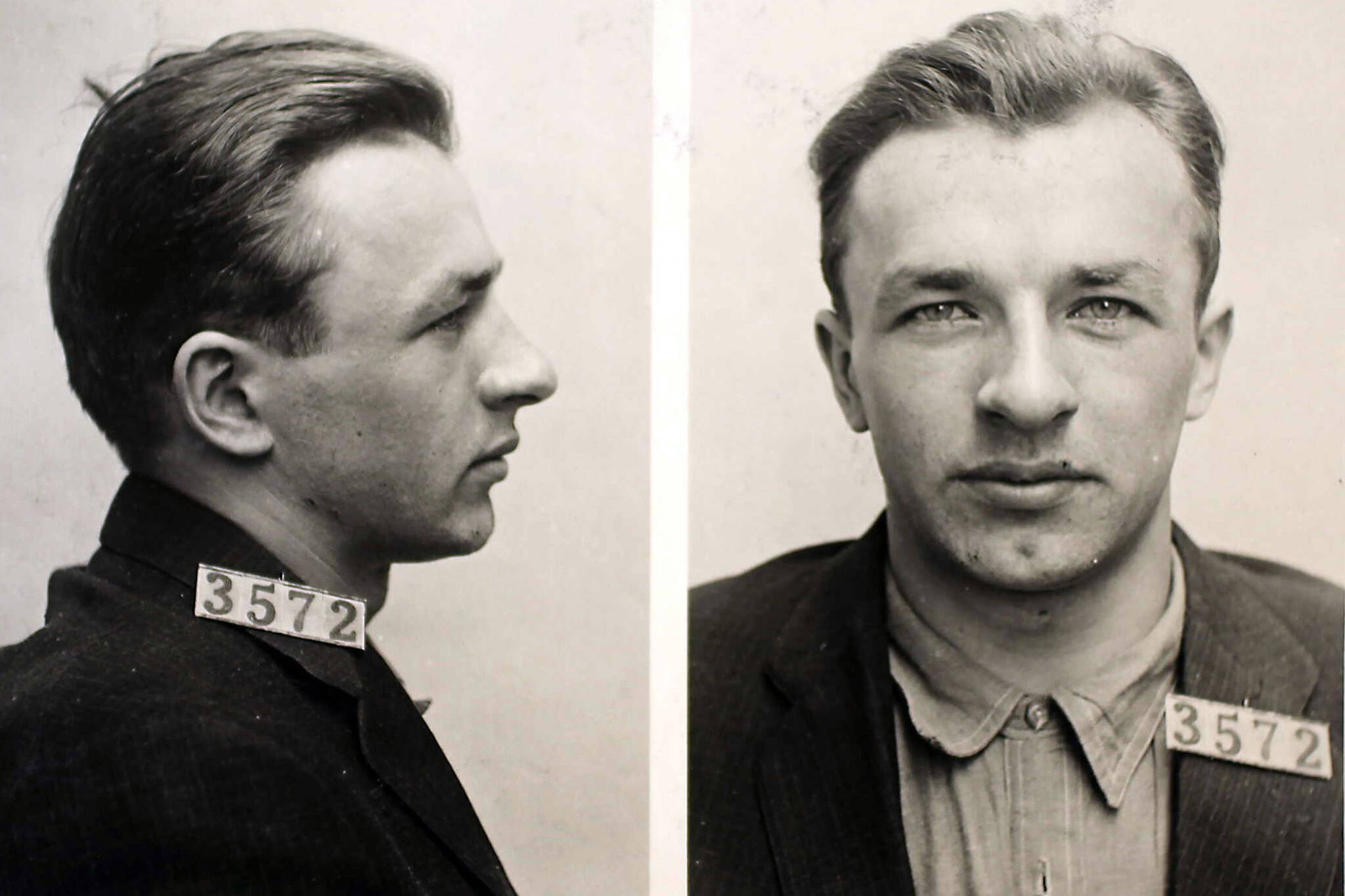

AUTHOR’S NOTE: William Dempsey killed two Alaskans in 1919 and was sent to prison in 1920 for his crimes. The first six parts of this story introduced Dempsey’s victims and the judge who presided at his trials. Part One also explained the alarm caused when Dempsey escaped from prison in 1940.

Letter-writing Campaign

On May 10, 1923, Alaska Territorial Gov. Scott Cordelle Bone received a typewritten letter from U.S. Attorney Sherman Duggan. Bone had written earlier to Duggan for guidance after receiving a request from convicted murderer William Dempsey, who was serving two life sentences at Leavenworth prison in Kansas for two murders in Alaska in 1919.

Bone, a former newspaperman from Washington, D.C., and Seattle, had been appointed to his Alaska governorship by Pres. Warren G. Harding two years after Dempsey’s trials and was therefore unfamiliar with Dempsey and his crimes.

To help the governor, Duggan supplied a brief summary of Dempsey’s murders—of Marie Lavor in Anchorage and Marshal Isaac Evans in Seward. He also discussed Dempsey’s convictions and the commutation of his death sentences to life in prison. He asserted that “no case in the history of Alaska has aroused such indignation as this, and no crime ever committed since the foundation of the territory was so wanton and depraved.”

He urged Gov. Bone to deny Dempsey’s request for copies of anything but his grand-jury indictments, each about one page in length. He described the full set of court transcripts and case records as “voluminous … perhaps 500 pages” and said that copies should be made available to Dempsey only if the prisoner himself paid the copying costs.

Finally, he informed Bone that Dempsey had also been writing to court officials and was attempting to build a case for executive clemency. Duggan argued that clemency should be denied: “I think I voice the sentiments of people here who know of the matter that (Dempsey) should have paid the penalty of his cruel and dastardly crimes with his life.”

Bone heeded Duggan’s advice. He instructed his secretary to send Dempsey a brief note explaining that only by paying the copying costs could Dempsey ever gain all the documents he sought.

Dempsey wrote back to the governor a few weeks later, crafting a three-part argument to persuade Bone to grant him the paperwork he desired.

Part one: He denied killing Lavor and claimed that Evans’s death was in no way murder in the first-degree.

Part two: He said he was destitute but still deserved the right to legally appeal his case and fight for clemency; therefore, Gov. Bone should grant his wish “gratis.” To do otherwise, he said, would prove that “only money can buy Justice.”

Part three: He sought sympathy. “I am a young man fast failing in health due to my imprisonment,” he wrote, an assertion refuted by his Leavenworth medical records. “My Beloveth [sic] Parents have almost become Paupers since my incarceration…. My Parents need me, & if I regain my liberty I shall return to their hearth & never, never leave it again.”

The subsequent response from the governor’s secretary indicated that Dempsey’s arguments were failing: “The Governor requests me to inform you that he is unable to comply with your request.”

Dempsey thus began directing his efforts and his arguments toward the man who had sentenced him, Charles Bunnell, now president of the college in Fairbanks.

The opening line of Dempsey’s first letter to Bunnell—dated March 19, 1926—got right to the point: “Many long, dismal years have elapsed since you presided at my trials, & I therefore beg to inquire whether you would at this late date, extend me your recommendation for clemency.” He told Bunnell that he was not the person who had killed Lavor and that his shooting of Marshal Evans did not constitute murder in the first degree.

Bunnell responded patiently and at length on April 7, but he ultimately denied Dempsey’s request. He reminded Dempsey that there had been witnesses to his slaying of Marshal Evans and that he had confessed to the killing of Marie Lavor. If some other person, or persons, was truly responsible in the Lavor death, he urged Dempsey to provide names and evidence. He promised to investigate any new information.

Thus it was, with this initial exchange, that Dempsey established a demeanor and a line of argumentation that would evolve only slightly over the next decade.

The tone was generally polite, but sometimes Dempsey’s frustration burst through, making him insulting or even threatening. A common refrain: “The Bible says, ‘Do unto others as you would want done unto you.’ You undoubtedly are a Christian. If so, prove your worthiness of its term or name.”

The arguments Dempsey employed generally fell into these five categories:

First: His trials had been a sham. He had been poorly represented by an unprepared defense. Other men had killed Lavor “in a drunken brawl” and made him take the rap. Also, the charges against him for killing Evans were improper. Besides, Evans had shot first. Dempsey had merely returned fire in self-defense.

Second: Since his incarceration, he had matured and had devoted himself to study. As a result, he said, “I consider myself sufficiently erudite & versed in Legal Business methods to enable me to henceforth live the life of an honorable, respectable citizen & become worthy of recognition in this modern civilized world.”

Third: His family back in Cleveland needed him desperately. As the years marched by, Dempsey told Bunnell that his mother lay at death’s door, crying out for him so that she could one last time hold her youngest son in her loving arms. He said the same thing years later about his father. He also spoke of the family’s declining financial fortunes and the need for him to sweep to their rescue.

Fourth: Dempsey’s childhood sweetheart—a woman whom he never named—continued to wait faithfully for him to be released from prison so that they could finally get married. “Truly,” he said, “I must have much goodness about me for a woman to remain loyal to me all these many years.”

Fifth: Dempsey was no longer the young punk he had been at age 19. Besides, he had already paid his debt to society, and everyone deserved a second chance. Granting him executive clemency would allow him to use the education and employment skills he had gained in prison to benefit society, rather than continue to be a drain on it.

Year after year, he and Bunnell exchanged letters. Year after year, Dempsey extolled his own virtues and spread the blame. And year after year, Bunnell continued to deny his appeals.

In 1936, out of frustration, Dempsey mailed a holiday card to Bunnell with this message beneath an illustration of a bright red bell tied up with a festive bow: “Although you wish me & my family misery this Christmas, I shall prove the better Christian by wishing you & your family a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year.”

Meanwhile, Dempsey had another strategy in motion: a trio of women who sought his salvation.