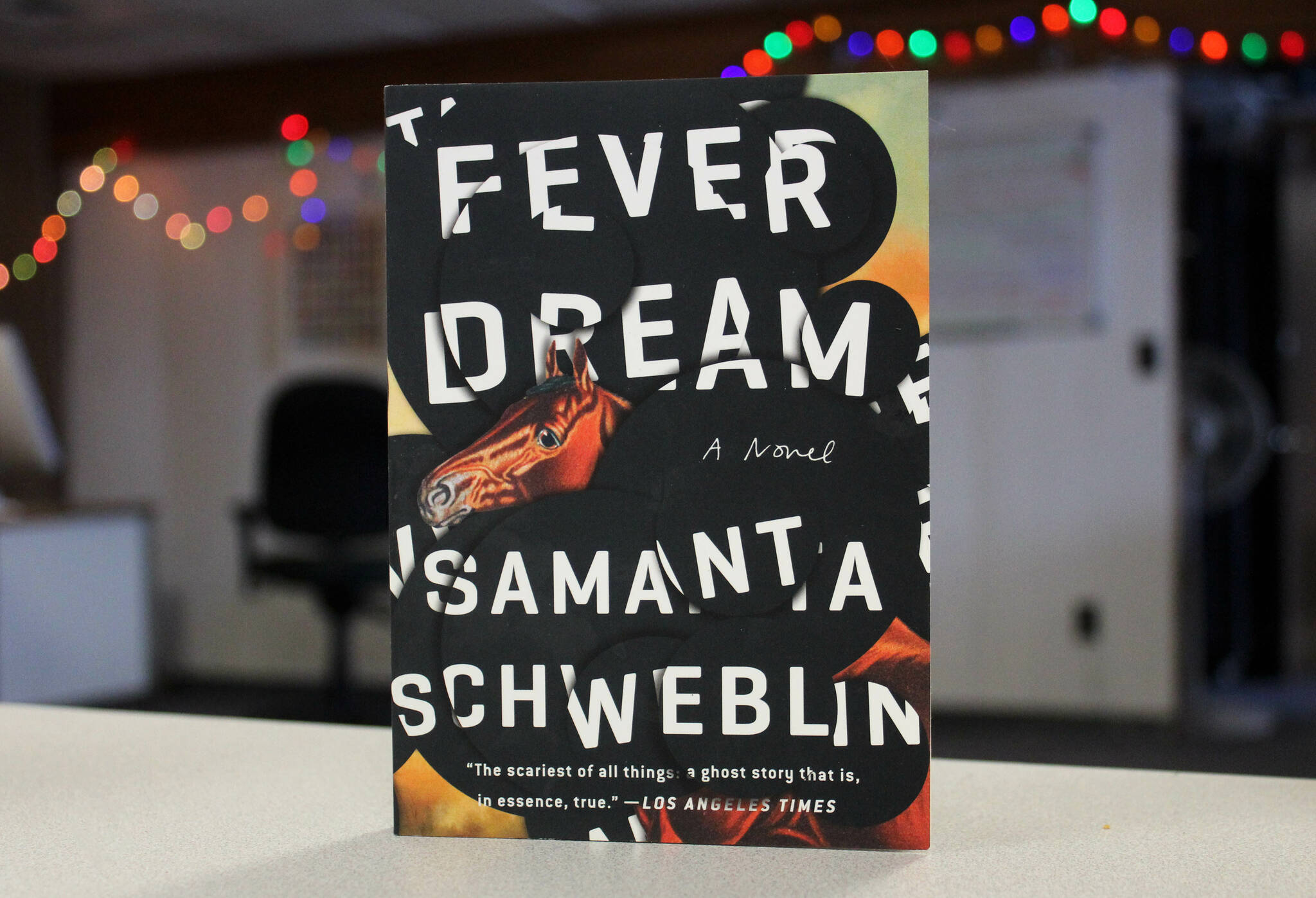

I picked up a copy of Samanta Schweblin’s “Fever Dream” during a trip to Anchorage last year. Sucked in by the title and the dramatic image of a horse in distress on the cover, I realized after finishing it last month that it was a good book to read during spring — in my mind, April is the time of the year to think about the earth.

Written as a conversation between protagonist Amanda, who lies dying in a hospital, and a young boy named David, “Fever Dream” is at once a haunting allegory for environmental devastation and a riveting tale of survival and the bond of motherhood. Since it was published, the book has received the Tigre Juan Literary Award, the Shirley Jackson Award for best novella and was shortlisted for The Man Booker International Prize in 2021.

Author Schweblin, who hails from Buenos Aires, told Lit Hub’s Bethanne Patrick in 2017 that, while “Fever Dream” could be set anywhere, the use of agrochemicals and pesticides is particularly problematic in Argentina. It is not clear from the book’s roughly 180 pages where the story is supposed to take place.

What is most compelling about the way Schweblin chooses to confront the effect of agrochemical use on humans is her use of the fictional novella format. It’s very different, for example, from Rachel Carson’s 1962 “Silent Spring,” which addressed the same topic and contributed to the United States’ ban on DDT use in agriculture as well as the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Though Schweblin spins a fictional and sensationalized tale in “Fever Dream,” the atrocities of which she speaks are no less real than those articulated in works of nonfiction and may, in fact, be more captivating.

A report published by The Associated Press in 2013, titled “Argentines link health problems to agrochemicals,” documented numerous cases where such chemicals were used in ways that both broke the law and adversely affected the health of residents. The report opens, for example, by describing two boys who were “showered in chemicals” while swimming in their backyard pool, despite there being a law against spraying agrochemicals within 550 yards of homes.

The same report found that cancer rates are two to four times higher than the national average in Argentina’s Santa Fe province, and that children in Argentina’s poorest province are four times more likely to be born with birth defects in the decade since biotechnology expanded industrial agriculture.

“Around here there aren’t many children who are born right,” David tells the protagonist toward the end of “Fever Dream.” “ … There are no doctors, and the woman in the greenhouse does what she can.”

The “woman in the greenhouse” refers to one of the book’s more elusive characters, to whom children exposed to chemicals are taken for treatment. There’s undoubtedly symbolism behind the greenhouse being the character’s solution to the harms of industrial agriculture. I took it to suggest that the solution to problems associated with industrialized farming may be a return to a more organic form of intervention when it comes to agriculture — think greenhouse.

For all the scenes of horses drinking from polluted streams and desperate mothers racing their children to the local witch doctor, there’s a race-against-the-clock feeling that keeps readers as invested in the harm of pesticide overuse as in any other horror story where a none-the-wiser character fights an enemy she cannot necessarily see or understand.

“Fever Dream” begs the question of what is the most effective way to communicate the implications of environmental harm. A common criticism by contemporary environmental activists, particularly when it comes to climate change, is that policies and practices don’t change even in the face of overwhelming evidence or information about a certain trend.

In 2023, it is certainly true that there’s no shortage of information for people who go looking for it. But what about the people who don’t? The use of agrochemicals in Argentina wasn’t an issue that was on my radar prior to reading “Fever Dream,” but it certainly is now. Would that still be the case if I was confronted with a scientific study or publication rather than a gripping horror novella? Who knows?

On its face, “Fever Dream” promises a haunting story of nature and survival. For those willing to look beneath the surface, though, it uniquely communicates a terrifyingly true reality.

“Fever Dream” was first published in 2014 in Spain by Literatura Random House. An English translation by Megan McDowell was published in 2017 by Riverhead Books.

Reach reporter Ashlyn O’Hara at ashlyn.ohara@peninsulaclarion.com.

Off the Shelf is a bimonthly literature column written by the staff of the Peninsula Clarion that features reviews and recommendations of books and other texts through a contemporary lens.