By Stephen Sigmund

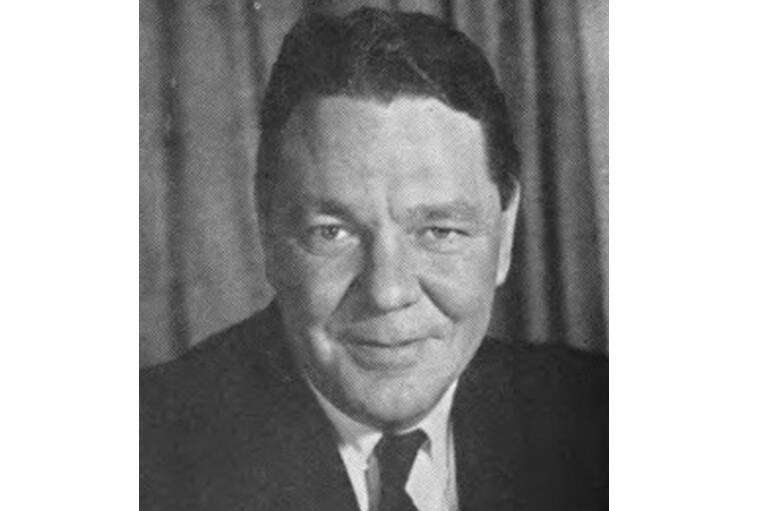

In October 1972, the U.S. House Majority Leader, Hale Boggs, a first term Congressman, Nick Begich, Begich’s aide Russell Browne and a pilot, Don Jonz, disappeared in a plane flying from Anchorage to Juneau. No trace of the plane, or the men, has ever been found. The cause has long been believed to have been caused by the small plane icing up in bad weather.

Hale Boggs was my grandfather.

Fifty years later, it is time to reopen a military search for the missing plane.

The mystery was the subject of a Podcast, from investigative journalist Jon Walczak, called “Missing in Alaska.” That podcast opened new questions, and most important, worked to more specifically pinpoint where the plane may have gone down.

Walczak’s premise for the podcast — a 1994 jailhouse claim by a convicted murderer named Jerry Pasley, who was briefly married to Begich’s widow, that the plane was intentionally targeted by mobsters with a bomb — while attention grabbing, leaves an enormous number of holes. Moreover, it has never been corroborated by anyone else.

His best reporting is around the facts surrounding the flight itself.

There is a strong case that the plane could now be found. Other small planes previously buried under ice and snow in Arctic conditions have recently been exposed by climate warming. In Alaska itself, wreckage and human remains from a military flight that crashed north of Anchorage in 1952 were unearthed from a melting glacier in 2020.

New technology like GPS and deep-water sonar drones could help pinpoint the location of the accident. And Walczak presents compelling evidence that the plane went down in a specific area.

For example, there were eye (or ear) witness accounts of hearing the plane fly over Whittier, Alaska, suggesting that it made its way through the treacherous “Portage Pass.”

The temperature on the ground the day of the crash was approximately 40 degrees, lessening the chances of icing and crashing in the far depths of Prince William Sound.

Walczak shows that the plane, if it had experienced serious icing, would likely have had time to contact the next radio point. He discovers that contrary to the NTSB’s report on the disappearance, the plane had both de-icing and anti-icing equipment. So even if the plane iced up, it had technology on board to buy the pilot time to radio and/or find a place to put down closer to land.

He concludes, therefore, that the more likely scenario was the plane went down quickly after clearing Portage Pass.

He reports on a fisherman’s find in 1980 of the tail of a Cessna airplane matching the colors and description of my grandfather’s plane, near Hinchinbrook Island at the entrance to Prince William Sound.

From all this reporting, Walczak pinpoints a smallish area in which the plane is likely to have gone down, between Whittier and Hinchinbrook Island. That is a distance of about 75 miles.

While much of the area is covered by water, with 21st century technology it is searchable, and small enough for a more comprehensive focus than the almost 600 miles of deep water and rugged mountains between Anchorage and Juneau.

With 50 years of improved technology and melting glaciers, this is a search whose time has come.

Because the real mystery isn’t a claim by a mobster and murderer more than 20 years after the disappearance. The real mystery is why no trace of the plane has ever been found. Solve that mystery, and any other speculation can be put to rest.

Stephen Sigmund is a grandson of the late U.S. House Majority Leader Hale Boggs, D-Louisiana. He is a public affairs consultant.