The future of the Kenai Peninsula Borough’s aging school infrastructure could end up in the hands of borough voters this fall. The Kenai Peninsula Borough School District Board of Education earlier this month gave their stamp of approval to a $65.5 million bond package that would address capital projects at school sites throughout the district.

That bond proposal, which must also be approved by the Kenai Peninsula Borough Assembly before it can appear on the Oct. 4 ballot, would pay for some of the school district’s biggest capital priorities, from high school tracks to new roofs.

Efforts to fund maintenance and repairs at school district facilities have been years in the making. The district last fall identified $420 million worth of maintenance, including $166 million worth of “critical needs.” Many of the projects represent deferred maintenance, or projects that have been put off.

It’s been seven years since borough voters last approved a bond package for school maintenance; subsequent bonds were soundly defeated. Bond packages proposed in 2020 and 2021 were delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to KPBSD Director of Planning and Operations Kevin Lyon — who has long led efforts to tackle the district’s deferred maintenance projects — there are a few reasons it’s a good time for a bond package together. Close collaboration between the school district and the borough — which owns district buildings — has meant some work is already underway.

Lyon said the borough has worked since last summer to tackle some of the district’s smaller, less expensive projects, such as school boilers, which are used for temperature control, and failing windows — like those that fog up between panes. Work on those smaller projects, Lyon said, is underway at all of the district’s 42 schools.

“Every single building is getting improvements on those things,” Lyon said. “Whether it be in Seward, or whether it be in Homer or Anchor Point, they’re working in all of our buildings regularly.”

Picking which projects end up in the bond package, Lyon said, isn’t easy because of how much work needs to be done. Something voters from all around the borough should keep in mind, however, is that getting big projects done frees up money, time and labor that can be used to tackle what’s left over, meaning projects that aren’t in the bond package.

“It is very hard with all the needs that are there to go through and choose,” Lyon said. “ … The bigger picture is taking some of these big items off the list frees up the funding we have at the borough to go and take care of other issues.”

An influx of oil money to the State of Alaska means the Legislature is better positioned to put money into school districts around the state. Gov. Mike Dunleavy announced earlier this year that the state is projecting a $3.6 billion revenue surplus this year due to spiking oil prices in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Lyon said the district is keeping its eye on how the Legislature acts — the state of Alaska is the biggest contributor to the school district’s annual budget. On top of that, there are two ways the state can fund school maintenance projects on the Kenai Peninsula.

The first is through a grant program. That program is currently active and awards money based on how competitive a project is. In evaluating whether or not a project is competitive, the Alaska Department of Education and Early Development considers 10 criteria and awards points depending where the project falls.

For example, one of the things the state considers is how old a facility is. Buildings between 10 and 20 years old get half a point per year in excess of 10 years, while buildings older than 40 years automatically get 30 points for that category. The more points a project gets, the more likely it is to get funded through the state’s grant program.

Even if a project is high enough on the list to receive funding, the state won’t foot the whole bill. Under the grant program the state pays for 65% of the total project. In the case of the Kenai Peninsula, the borough has to come up with the other 35%, because all KPBSD facilities belong to the borough.

The borough was awarded money through the state’s grant program, for example, to pay for the construction of a new school in the remote community of Kachemak Selo, at the head of Kachemak Bay. Borough voters previously defeated bond packages that included funding for the school, which serves 31 students.

Another way to get the state to pay for a project, however, is Alaska’s school bond debt reimbursement. That program has been closed since 2015, but a bill currently before the Legislature — House Bill 350 — would open it back up.

As its name suggests, the program uses state money to pay for part of the bonds a borough sells to fund projects. Like the grant program, the bond debt reimbursement program splits the total project cost between the state and the borough. Contingent on legislative approval, the state pays 70% of the bond payment for “eligible space” projects and 60% for space not considered eligible space.

Eligible space is a square footage amount tied to a school’s enrollment. Space that is not eligible refers to any projects or expansion that exceeds the square footage calculated per student.

As the Legislature mulls the best way to fund school projects, research published last year finds that the state is already not funding school projects at the rate it should be.

A March 2021 study out of the University of Alaska Anchorage’s Institute of Social and Economic Research found that the State of Alaska “is not spending what is needed to maintain, renovate, and renew its K-12 school buildings.” Authored by ISER research professor Ben Loeffler, the study found that Alaska has historically spent about 80% of what it should be spending on annual school property upkeep.

Loeffler wrote that the industry standard for annual school property upkeep is 4% of the current replacement value — that amounts to $374 million annually in Alaska. The state’s annual capital spending between 2000 and 2014, however, averaged $300 million, Loeffler wrote.

The average is even lower over the last six years, Loeffler wrote, noting that “K-12 capital spending fell dramatically after (Alaska’s) fiscal crisis.” The state’s annual capital spending over the last six years averaged $124 million — about 33% of the recommended annual investment, Loeffler found.

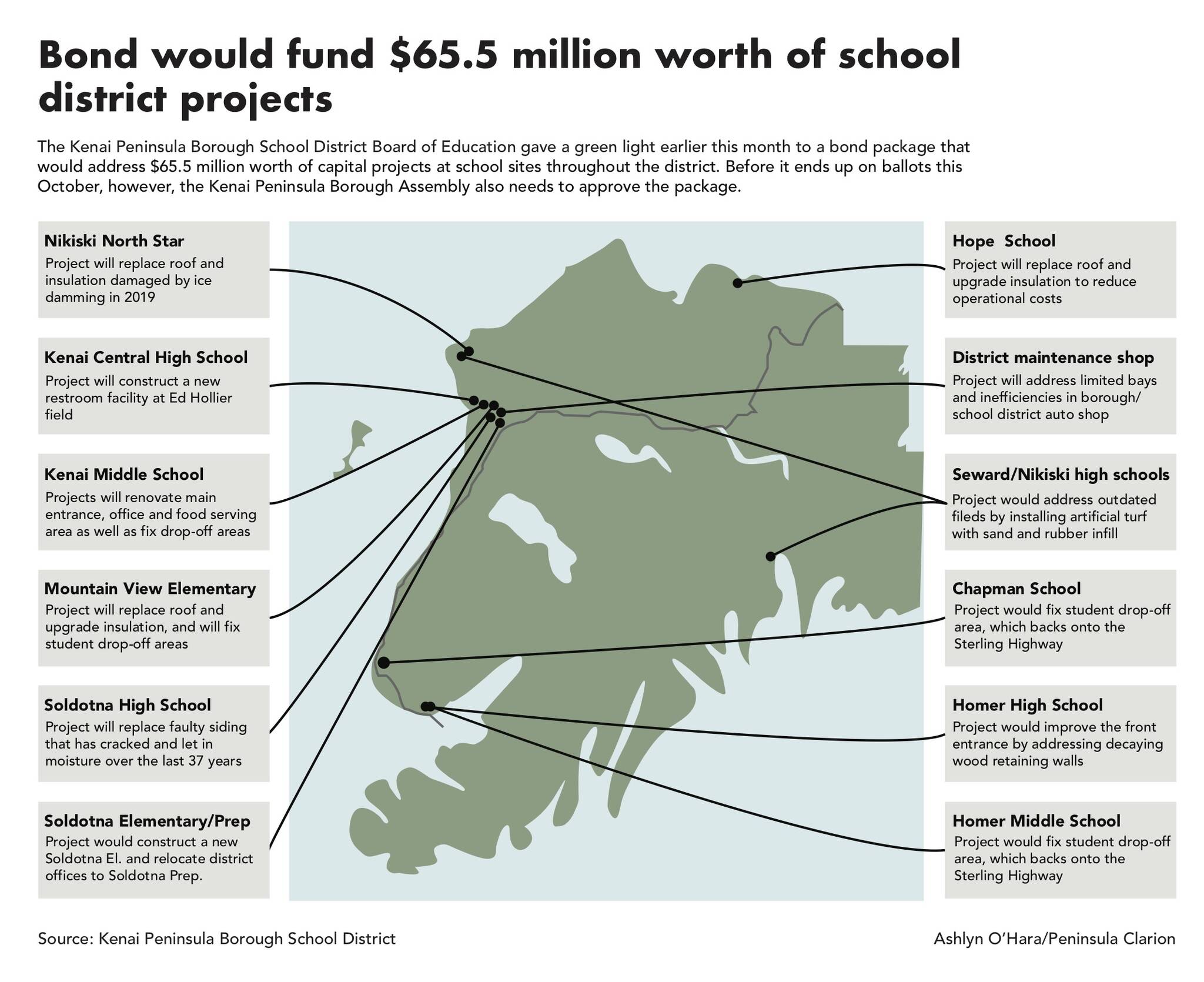

Regardless of where the state lands on school capital funding, the Kenai Peninsula Borough and the school district are moving forward with the bond proposal. The bond package that could end up before borough voters this fall describes $65.55 million worth of projects.

The most expensive project on the list is the reconstruction of Soldotna Elementary School, which is estimated to cost around $21.5 million. The second most expensive project is the repurpose of the Soldotna Prep School building, which is expected to cost around $18.5 million.

As part of the Soldotna Prep School projects, KPBSD’s district office, River City Academy, Soldotna Montessori and Connections Homeschool would all be relocated to the prep building, which is currently sitting vacant and which costs the Kenai Peninsula Borough $300,000 annually to maintain, according to a description of the bond package prepared for school board members.

“That’s a big project, but it’s going to save us a lot of operating costs, it’s going to give the facility new life (and) it’s going to be better for the kids,” Lyon said of the project.

Other projects in the proposed bond package include $5 million work to expand the efficiency of the district’s automotive maintenance shop, $4.8 million worth of metal roof replacements at Nikiski North Star Elementary, Mountain View and Hope schools and $5.5 million for student drop-off facilities at Chapman, Homer Middle, Kenai Middle and Mountain View Elementary schools.

Also included in the proposed package is $500,000 for the construction of new concession and restroom facilities for Ed Hollier Field at Kenai Central High School. The school has been working to crowdsource $250,000 needed for the project since February, citing the high cost of seasonal port-a-potty rentals and lack of available district funds.

Improvements to the front entrance at Homer High School, safety and security renovation at Kenai Middle School and the installation of turf fields at Seward and Nikiski high schools are also described in the proposal.

The estimated cost to borough taxpayers would be about $45 for every $100,000 taxed if H.B. 350 does not pass and about $25 for every $100,000 taxed if H.B. 350 does pass. That’s per Kenai Peninsula Borough Purchasing and Contracting Director John Hedges, who has been working with Lyon on school maintenance issues on the borough side.

Though the cost estimates are not final, Hedges told KPBSD board of education members on May 2 that H.B. 350, if passed, would reliably cut those estimates in half.

Lyon has voiced in the past the need for a bond package that is “just right.” He said that no group of projects will make everyone happy, but that voters should keep in mind passage of the package stands to benefit all schools in the borough by taking care of big, expensive projects.

The bond package has already been approved by the KPBSD Board of Education. Before it ends up on ballots this October, the Kenai Peninsula Borough Assembly also needs to give its thumbs-up. Lyon said he’s hopeful that the assembly will give their approval because the list of projects is the product of collaboration between the borough and the district.

More information about the proposed bond package can be found on BoardDocs, the district’s digital repository for documents.

Reach reporter Ashlyn O’Hara at ashlyn.ohara@peninsulaclarion.com.