By McKibben Jackinsky

Staff writer

As word spread that the belly of the Exxon Valdez, a tanker carrying Alaska oil from Valdez to Long Beach, Calif., had been ripped open and its contents were pouring into Prince William Sound, Homer-area residents were filled with an urgency to do something.

They washed beaches and helped rehab oil-soaked wildlife. They built booms in defense of coastlines. They left their homes to work at remote sites. They broadcast what was happening so others would know. They gave orders and took direction. And they felt their lives change.

Not too far beneath the surface of the impacted beaches, evidence of the millions of gallons that spilled from the ship can still be found. The same can be said for those who worked to minimize the damage.

Marion Beck

Halibut Cove

When the spill occurred, Halibut Cove resident Marion Beck was in the middle of building an art gallery and anticipating a busy summer season.

“Oh my god, it was sickening,” said Beck of the spill. “It was one of those things that just got bigger and bigger and bigger. … Everybody kept saying it would clean up, but it didn’t.”

With a degree in animal science from Cal Poly University and a history of doing work with seals for the National Marine Fisheries Service, Beck was contacted by NMFS almost immediately after the spill occurred and asked to help rehab impacted seals, a project that lasted about four months.

Halibut Cove offered the perfect location to construct a pen for the arriving seals, some of them suffering from marine mammal stress syndrome.

“It was away from everybody and we could be pretty private about it,” said Beck.

The death of one seal resulted in a crucial piece of information.

“I was talking with a center in the Netherlands, sending seal blood there because they were the only one testing seal blood and when I told them what happened, they said what to do was make oatmeal tea,” said Beck of a remedy that had proven successful

treating starving refugees of World War II. “I tried it right away, learned a lot and got a lot of good documentaries and research papers people sent to me.”

Exxon representatives arrived at Halibut Cove to photograph the release of the rehabbed seals, but Beck, whose work was paid for by NMFS rather than Exxon, was very clear about setting boundaries. She told them they could photograph from land, but could not be near the pens. That arrangement proved unsatisfactory to the Exxon personnel. Their response proved unsatisfactory to Beck, who was “repulsed by the arrogant superior

presence.” She put them in a skiff, rowed them to their helicopter and they left before the seals were released. Beck’s painting, “The Three Faces of Greed” reflects her reaction to that encounter.

“They (Exxon) were just throwing money at it to try to make people look the other way. … And then, of course, they strung everyone along … and then didn’t pay us. There were no rules,” said Beck. “It really makes you more anxious about what’s transpiring now because you know no one will fix our world if they ruin it. They couldn’t fix it.”

Mike O’Meara

Homer

Homer News political cartoonist Mike O’Meara was in Anchorage for the annual Alaska Press Club’s “press week” when he saw the headline about the Exxon Valdez spill.

“My reaction was ‘well, it finally happened,’ because, like so many people who had followed the whole development of the pipeline and the decision to terminate (the pipeline) at Valdez and run it down the coast by tanker, I knew there’d be a disaster at some point. It wasn’t if but when and how bad it would be,” said O’Meara.

After returning to Homer, O’Meara cranked out one cartoon after another, using his artistic ability and knowledge of the oil industry to help the public understand what was happening.

“But I wanted to do something more tangible than that,” said O’Meara.

The opportunity came when he was asked by the Pratt Museum to be curator of “Deadly Waters: Profile of an Oil Spill,” an exhibit about the spill.

“I was reticent at first to do it because, for one thing, I had just gotten my studio built and was doing a large amount of metalsmithing, silver and gold work, selling a lot of it through the Limited Edition gallery in Homer and also in Anchorage and by word of mouth,” said O’Meara. “But the more I thought about it, I realized I’d been wondering what to do and here was someone offering an opportunity and it was the kind of thing I was pretty knowledgeable about.”

The exhibit opened to standing-room-only crowds. “(The museum) was full. Many days, there was literally no way to sit anybody down. It was shoulder to shoulder.”

A traveling version of the exhibit crisscrossed the country for 10 years and was viewed by an estimated two million people.

“When the ‘Darkened Waters’ exhibit became complex and demanding…I didn’t have time to produce jewelry anymore,” said O’Meara. “The main thing I was doing was museum work and I began working on other things, developing and coordinating projects related to science and environmental education. … There are certain regrets when you leave something behind you cared about and that held a lot of promise, but of course it was replaced initially by catastrophe, but ultimately by something equally as satisfying and productive. I’m happy at the way it came out and I won’t complain.”

Roger MacCampbell

Homer

As the state of Alaska’s chief park ranger on the southern Kenai Peninsula, Roger MacCampbell heard about the spill “the same way everyone did, on the news.” In short order, he was in a plane, surveying the Kenai Peninsula’s outer coast, looking for signs oil was headed this direction and awaiting direction.

“I was kind of expecting a system to fall into place, an incident command-response system with marching orders,” said MacCampbell. “I kept calling, saying ‘what are we going to do’ and there was no response.”

Finally given authority to start organizing, MacCampbell brought rangers from across the state and set up camps along the peninsula’s south side to monitor cleanup activities.

“It was crazy. Like a war zone. It looked like the landing at Normandy Beach in some areas,” said MacCampbell. “People were showing up, looking for work. It was right out of the Grapes of Wrath, people from all over the world wanting to help.”

Equally “quite crazy” was the amount of resources thrown at the response. “Exxon showed up and basically started writing blank checks. We were getting equipment, things on the state budget we never got before and haven’t had since,” said MacCampbell.

There was an abundance of cleanup techniques tried and, with multiple agencies responding, confusion over who was in charge. One example was cleanup efforts at Gore Point, with two Coast Guard officers coming to MacCampbell for permission to work in that area.

“I had a blank permit in my hand and neither one of us had a pen. The only thing I had to write with was a crayon and I wrote a permit for them to take heavy equipment on the beach,” said MacCampbell. “They said, ‘We can’t. It’s a state park.’ I said, ‘I know. I’m the park ranger.’”

Following a year of almost non-stop work resulting from the spill, a critical incident stress team arrived to debrief individuals involved in the response. “They ended up crying and we ended up debriefing them,” said MacCampbell, who views what happened in 1989 as a good wake-up call.

“An unfortunate one, but it put better systems in place,” he said. “I’m not sure that we have the resources for a massive response, but CISPRI (Cook Inlet Spill Prevention and Response Inc.) and different organizations are there now to help. We didn’t have that in place at all…. I think we’re better prepared. We just can’t forget.”

Willy Dunn

Homer

Willy Dunn was constructing his dream home in March of 1989.

“I remember walking into my kitchen to make a cup of coffee and turning on the radio and hearing on KBBI news that an oil tanker had run aground in Prince William Sound,” said Dunn, who thought to himself, “This is going to be a bad incident.”

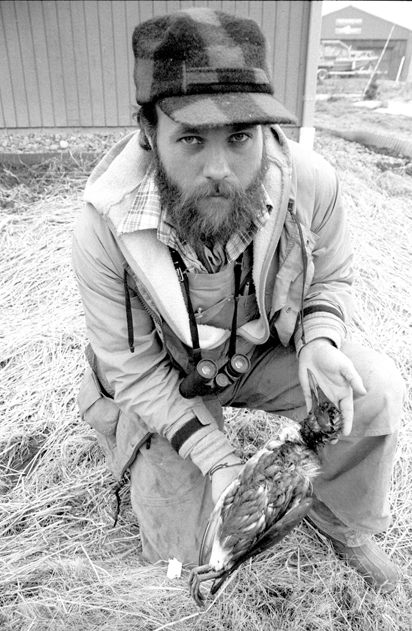

Dunn began patrolling Homer-area beaches, alert for signs of oil and actually finding dead oiled birds long before oil made its way into Cook Inlet.

“What had happened was that birds were encountering oil offshore and then moving onshore and dying or dying and being washed ashore by the currents,” said Dunn.

After hearing that Alaska State Parks was looking for volunteers to do wildlife recovery on the peninsula’s outer coast, Dunn signed up. On the boat, he and others were told they couldn’t volunteer but had to be employees of Veco, the company working with Exxon in the spill response effort.

“So, basically, as we were on the boat on the way out there, they gave us employee paperwork and we went from being volunteers to employees,” he said.

For the next several weeks, Dunn spent his days working along the shore and his nights sleeping on a boat. The workers’ mission was to recover any oiled wildlife and send live animals back to Homer for rehabilitation.

“But the time I was out there, we got one loon, saw a few oiled sea otters we weren’t able to capture, but picked up literally thousands of dead, oiled seabirds,” said Dunn. “It was horrible. Just horrible. On so many levels.”

Also disheartening for Dunn was the lack of direction, as well as the attitude of some of the responders.

“Some people were very diligent and wanted to work very hard to do what they could to help wildlife and cleanup the oil, but a lot out there were trying to make as much money as they could and do as little as they could,” he said.

After about a month, Dunn, who now works as a fishery biologist for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, hitched a ride back to town on a helicopter and decided to stay home.

“I have become much more politically active, trying to be active with my community and do what I can to help the community, to help the environment, to keep our habitat and wildlife and fish healthy,” said Dunn of how the spill changed his life. “On the other hand, it’s made me a little bit cynical of our government. That was one of the first instances when I realized that big corporations are more powerful than our government. In the end Exxon basically suffered very little.”

Wally Kvasnikoff

Nanwalek

Shortly after hearing oil was leaking from the Exxon Valdez into Prince William Sound, Nanwalek resident Wally Kvasnikoff got a bird’s eye view of the area.

“I couldn’t visualize it when they were talking about it on the news, but then we flew down there and saw all that oil and I thought, ‘holy cow,’” said Kvasnikoff.

Within days, Veco began hiring workers to help with the spill and Nanwalek residents turned out in full force.

“The whole village went to work and our kids felt like orphans at home so they said, ‘No, mom, you’ve got to stay home,’” said Kvasnikoff, whose wife returned home, while he was assigned to oversee a crew at Chatham.

“The funny thing was that we’d pick up a bag of absorbent pads (for mopping up oil) and then they wanted us to multiply that by four when we were reporting,” said Kvasnikoff. “In other words, I think they were trying to make it look like we were picking up more oil than we did all through the summer and into the fall.”

Kvasnikoff also wondered about directions given to a boat with a hull full of dead birds. “They were told to take them out as far as they could go and just dump them,” said Kvasnikoff, upset by what he was witnessing.

Also distressing was the devastation to Nanwalek’s subsistence foods gathered from the beach.

“We couldn’t eat our fish. We couldn’t eat nothing that we were used to. It just tore our hearts out,” said Kvasnikoff. “It was four or five years before a guy working with Fish and Game said to go ahead and eat it.”

Nanwalek residents also were impacted by the amount of dollars spent on spill response.

“They were dumping money on us. … ‘Here’s $2,100 a week. Go work,’” said Kvasnikoff of money, much of it spent on drugs and alcohol. “I myself became an alcoholic afterwards. It still tears my heart out. For about a year and half, I was just saturated with all that stuff. You could have all the drugs you wanted. All the alcohol. It changed lives.”

Those changes have been long-lasting.

“Even to this day I carry a heavy burden from that damn oil spill. … I’m 58 now and I’ve never witnessed anything like that. It was horrifying. It just tore our lives up,” said Kvasnikoff. “Back in those days we didn’t have a lot of use for money. We didn’t need money. We lived our subsistence lives. We had each other. It was a healthy village. … Now I do my subsistence at the store.”

Mavis Muller

Homer

Artist Mavis Muller was away from Alaska in March 1989, serving as assistant curator for “Gaia Pacifica,” an exhibit preparing to open in San Diego, Calif. The exhibit was a fundraiser for environmental issues, with a focus on water.

Upon hearing about the spill, Muller immediately contacted a friend in Valdez, who arranged for four quart-size jars of Prince William Sound’s oily water to be shipped to Muller.

“In a room full of people with cameras set up and reporters, I walked in with that box and lifted out those quart jars with oil water,” said Muller of her effort to make what was happening in Alaska visible to others.

Using a fish tank, Muller and other artists created a simulation of the spill as part of the exhibit.

When Muller originally came to Alaska in 1984, her focus was the deforestation of the Tongass National Forest.

“I came to Alaska as an artist-naturalist. I like to use the word ‘artivist’ because I use my art as my activism,” said Muller.

When the Exxon Valdez spill occurred, Muller refocused. She became part of a volunteer, independent cleanup effort at Mars Cove. Their logo was a clenched fist holding a trowel. Their motto, painted by Muller on an oil-covered piece of plywood that washed up on the beach one day, paraphrased the Irish author Edmund Burke: “There is only one thing necessary for the triumph of evil. That is for good people to do nothing.”

“It was an unprecedented situation that required unprecedented collaboration,” said Muller, who also created a series of banners for communities impacted by the spill. One of those banners became the cover of “The Day the Water Died,” a book about the Exxon Valdez spill.

“That’s the thing about visual art,” said Muller. “It isn’t a bully, doesn’t make you look at it or feel anything, but if you choose to you might find some bit of alchemy and transformation in it.”

Muller continues to use her artivism to help others process the personal impact of oil spills. She was invited to participate in an event marking the 10-year anniversary of a spill in Spain and is currently in Louisiana, participating in an event commemorating the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

“I have very clear evidence, undeniable evidence that this kind of art matters,” said Mavis. “And I’m going to keep this story alive because that’s how we learn.”

McKibben Jackinsky can be reached at mckibben.jackinsky@homernews.com.