For scientists to connect to citizens, it’s as easy as A-B-T.

On April 17 at the Kenai Peninsula Fish Habitat Partnership’s Science Symposium, keynote speaker Randy Olson tossed out a new approach to scientists. Rather than just laying out the facts, scientists should inspire people with something elemental to the human experience — stories.

“The public’s not interested in science,” Olson said. “The number one thing the general public is interested in is other human beings.”

How do you get people interested in other human beings? You tell them stories, Olson said.

“A story begins when something happens,” he said. “This is the fundamental rule number one that you have to learn at a deep level.”

A Harvard University educated marine biologist, in his 30s Olson gave up tenure at the University of New Hampshire and went to Hollywood — and then he became a filmmaker. Ever since, through his films and writing like “Flock of Dodos,” he’s been looking at how storytelling can work for science.

Storytelling has three elements: A, for “and,” B, for “but,” and T, for “therefore.”

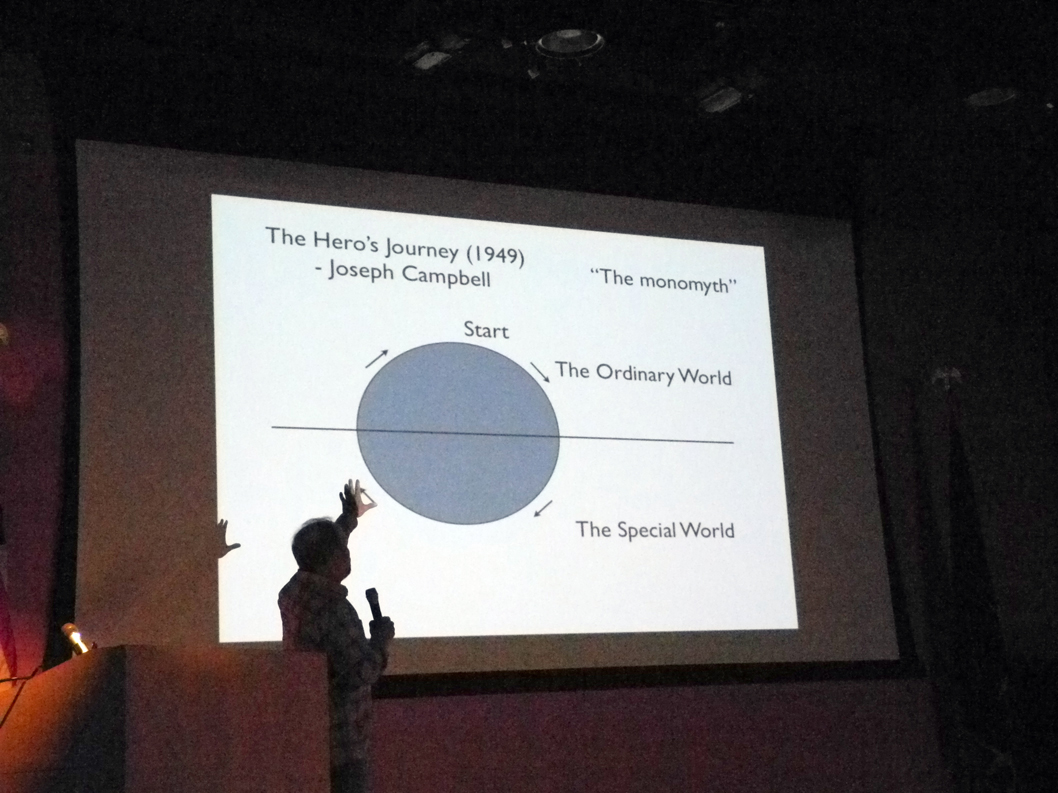

Olson spoke of the work of Joseph Campbell, who realized stories have a basic template, the monomyth. A story begins in the ordinary world, like Dorothy in Kansas, “and then something happens that changes everything,” Olson said. Dorothy is swept up by a tornado and taken to the land of Oz.

The “and” of Dorothy’s world is the “and” in the A-B-T formula: Dorothy lives on a farm in Kansas and she has a dog named Toto.

The “but” is what takes a character into an extraordinary world. For example, Dorothy lives on a farm in Kansas and she has a dog named Toto, but then a tornado takes her away.

When scientists present papers, often what they do is write a lot of sentences with a series of “ands,” what writers call an expository lump. Trey Parker, the creator of the irreverent animated series “South Park,” came up with a principle he calls “the rule of replacing.” In a series of sentences, Parker said every place he sees the word “and” he tries to replace it with “but” or “therefore.”

“The word ‘but’ establishes a sense of conflict and tension,” he said. “But then — now we’ve got a story.”

“Therefore” comes in with the other part of Campbell’s monomyth. Going from the ordinary to the special world is only part of it. The story also is about getting back to the ordinary world. Therefore, once Dorothy learned the secret of the Wizard of Oz, all she had to do was tap her ruby slippers and say, “There’s no place like home,” so she could return.

How does that work for scientists?

Scientists need to figure out how to frame their studies as a story. For example, when he first made his film, “Flock of Dodos,” it started out as a series of episodes about evolution vs. intelligent design, Olson said.

That was boring. He found a tale to hang the film on when he framed it as “the story of the journey to defend a damsel in distress from the villain who lives next door,” he said — that is, his mother, bothered by a neighbor who criticizes evolution and supports creationism. Olson’s film looks at who funds the intelligent design movement, but also how scientists are like extinct, flightless birds when they try to talk about science.

In another example, Olson mentioned the book, “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks,” by Rebecca Skloot. Lacks is the woman whose tumor cells were harvested to do cancer research, but rather than start with how that research works, Skloot looks at who Lacks was, how it happened that her cells were used and then why they are so important.

“That’s a role model for broad science communication,” Olson said.

Storytelling also means finding a likable voice to tell the story. Often the story is someone humble and self-deprecating.

“I can’t emphasize enough the need to find voices that are trusted,” Olson said.

Other tricks that help are keeping the story simple and looking for superlatives.

“Superlatives are storytelling gold,” he said. “That’s a rule to have in your head.”

At their heart, stories connect with people. Our brains are hardwired to react to stories, and certain kinds of stories. Neurological studies have shown this, Olson said. When viewers see a story that makes sense and is coherent, the brains of everyone react the same way. When they see something that doesn’t make sense, that is a jumble of images, their brains react in different ways.

“Great stories live forever, and great stories will always find audiences,” Olson said. “I see endless possibilities in storytelling.”

Michael Armstrong can be reached at michael.

armstrong@homernews.com.