When two artists join lives together, it’s inevitable that their art also will merge. For Asia Freeman and Michael Walsh, a couple who met through art and have been married for 5 years, sometimes that collaboration becomes a synthesis, as with their installation art work, “Backyard, Alaska,” shown at the Pratt Museum in the spring of 2010.

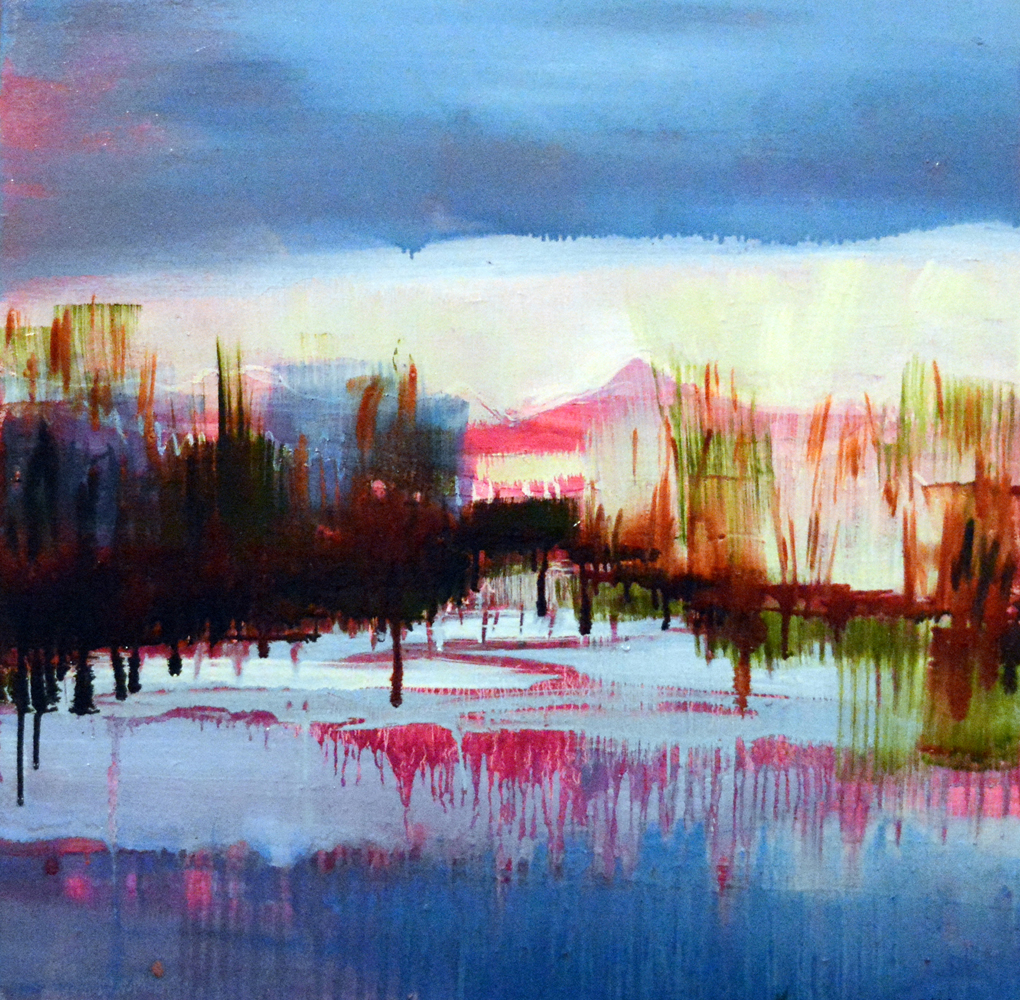

But as with marriage, spouses also can preserve their individuality while at the same time nurturing and supporting each other’s artistic vision. That’s the genesis of “Watermark,” Freeman and Walsh’s show that opened this month at the Pratt Museum and continues through Aug. 2. Freeman, who works in oils, and Walsh, a digital video filmmaker, each have distinct paintings and films. They created the work in their joint studio, but also share “a sensual language of mark making with a focus on water as media and muse,” they write in their artistic statement.

Both artists take as their inspiration the landscape and environment of Kachemak Bay — the kind of show a museum of both art and natural history seeks.

“The art work addresses connections to place, which is a perfect fit for the Pratt,” said director of exhibits Scott Bartlett at the show’s opening on June 4.

Freeman paints intimate, sensuous landscapes using water miscible oils, which give her art a translucent glow. Walsh works in 16mm film projected digitally as well as in video, all edited and manipulated so that the videos appear to be ever changing paintings. Musician Joe DeCino wrote the score, an audio loop, for the title piece, Walsh’s “Watermark.”

“I think we’ll be hearing that guy in the movies,” Freeman said. “He’s that good.”

“It helps the heart of the show that Asia and I put together,” Walsh said of the music.

“Watermark,” the title of the show as well as Walsh’s main work, has several meanings.

“I think it refers to the way water itself paints the surface,” Freeman said. “It paints the planet. It makes all kinds of interesting shapes and texture on a canvas and on film with respect to light, contrast, color.”

“It’s the play on ‘watermark,’ how photographers place their watermarks on photos, and obviously the reference of water, Kachemak Bay specifically, like mark making,” Walsh said.

Freeman said there’s another element to mark making. At her art school students signed their paintings on the back, not the front. She learned that an artist’s style was her signature.

“We could look at a certain artist, we could look at a Monet, and recognize the signature of their mark,” she said.

Although they created distinct art, Freeman and Walsh both said the process still felt collaborative.

“At times I’m not sure if it’s about collaboration or resonance,” Freeman said at the art opening.

She expanded on that in a follow-up interview.

“He would sometimes say, “I think you might be done. Why don’t you take a walk so you don’t lose this and push it too far?’” Freeman said.

“We were touching base throughout the process,” Walsh said. “It was just a shared experience. Often she would be doing something. I’d look over and make a comment about a mark I made. She would ask, ‘What do you think of that?’”

Freeman said she starts a painting with the outer image, a sense of a specific place like Yukon Island. Her paintings are landscapes only in the sense that they start with that natural vision.

“And then what happens is you start to put paint down, and after awhile I look at what’s there and try to resolve it,” she said. “The idea of seeing the abstraction in nature and looking for the repetition in the most simple marks possible has been my search for me.”

That narrow focus also lead Freeman into exploring paint itself.

“It’s like a language that is intricate and particular. I just don’t even want to make it translate nature. I want it to express and explore its own nature,” she said of the act of painting. “It’s fast and slow and not really in between, like riding a wild animal … I love it when it works, but sometimes I feel like I have whiplash and my feet are tired and I have to leave it alone.”

Walsh’s approach to art also gave him an entry point into his own work, Walsh said. Primarily an abstract artist, he shoots for images, sometimes turning the camera upside down or blurring the shot. Rather than look for abstraction as he usually did, with this show Walsh said he looked for beauty in Kachemak Bay and the world around him.

“I’m still looking for the light,” he said. “I just was taking these long shots. I gave myself this rule: Every time I hit ‘record” it would be at least a 30-second take. It started with shooting the literal. I didn’t even try, it’s so damn beautiful. Even on a stormy day it’s beautiful.”

Walsh said he also saw collaboration in the daily lives of two artists.

“Working with the same inspiration with water, Kachemak Bay, and just sharing it along the way,” he said. “Even if it’s just sitting on the couch or the dinner table or driving up to Anchorage, we would be talking about it in some form.”

When they hung the show, Walsh said until then he didn’t realize how much more intimate the collaboration had been compared to other shows.

“It was sensual. It was real, It was honest. It was loving. It was trust. It had all these elements in our daily lives,” he said. “There’s so much love in there. Love for land, love for art, love for landscape, our relationship. It’s just in there from top to bottom.”

Michael Armstrong can be reached at michael.armstrong@homernews.com.